Liber de Synodis seu Fide Orientalium (c.358)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

Hilary of Poitiers' influential theological treatise written in 358/359 AD during his exile in the East, analyzing and explaining Eastern synodal creeds to Western bishops. The work defends Nicene orthodoxy while building bridges between "homoousios" (same substance) and "homoiousios" (like substance) theological positions, demonstrating that many differences between Eastern and Western confessions were more terminological than substantive. This pivotal text helped reconcile theological factions and strengthen Trinitarian doctrine during the tumultuous Arian controversy.

Historical and Theological Context

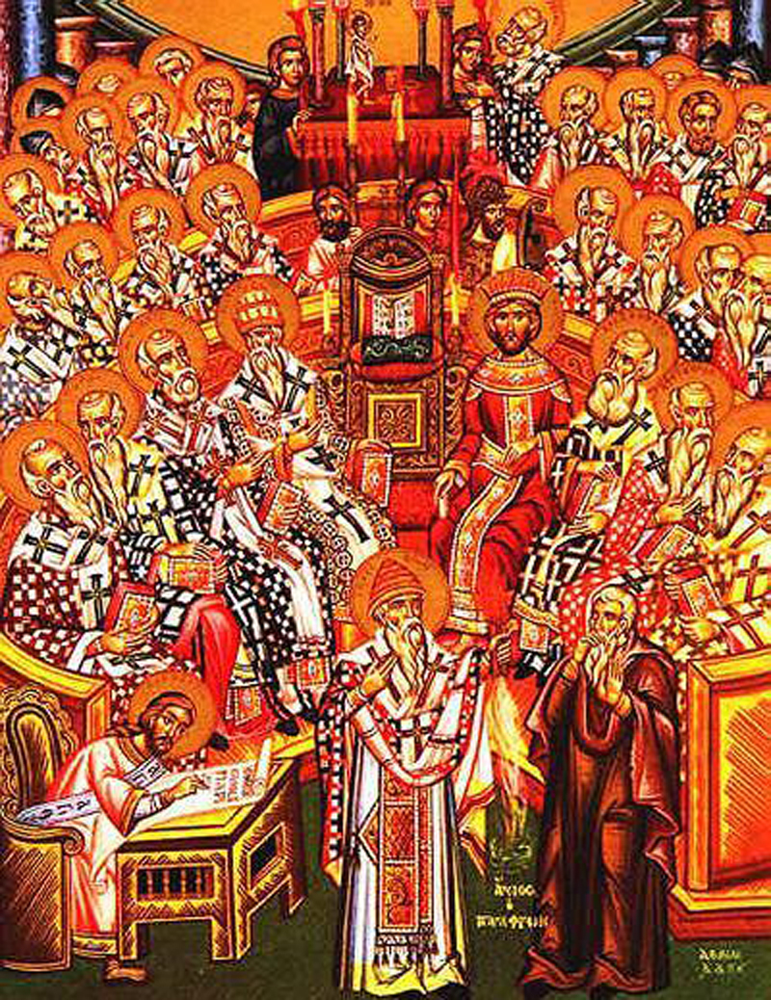

A 16th-century icon of the First Council of Nicaea (325 AD). The Nicene Council affirmed the Son’s full divinity (homoousios, “of one substance” with the Father) against Arian teaching. This established the theological backdrop for Hilary’s work.

The Liber de Synodis seu Fide Orientalium (“Book of Synods or on the Faith of the Easterners”) was written in AD 358/359 by St. Hilary of Poitiers, a bishop exiled during the Arian controversy (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia) (EarlyChurch.org.uk: Hilary of Poitiers (315 - 367)). After the Council of Nicaea (325) defined the Son as homoousios (one in substance) with the Father, disputes erupted between Nicene orthodoxy and various Arian or semi-Arian factions. By the mid-4th century, Eastern bishops had promulgated multiple creeds at regional synods—some rejecting or modifying Nicaea’s language. Hilary, a staunch Nicene (“Athanasius of the West” (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia)), found himself in the Eastern Empire (Phrygia) due to exile (356–360) under Emperor Constantius II (EarlyChurch.org.uk: Hilary of Poitiers (315 - 367)) (Saint Hilary of Poitiers - Bishop, Doctor of the Church, Orthodoxy - Britannica). Immersed in the East, he learned the theological nuances and divisions among Eastern bishops (EarlyChurch.org.uk: Hilary of Poitiers (315 - 367)). Concerned that the Western churches misunderstood these Eastern formulations, Hilary set out to bridge the terminological gap dividing the orthodox East and West.

In late 358, Hilary received correspondence from Gallic bishops who had refused communion with the Arianizers and condemned the blasphemous Second Sirmian Creed of 357 (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). They requested an account of the Eastern synods’ creeds. Hilary was overjoyed at their fidelity and eager to dispel mutual ignorance (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Early in 359 he composed De Synodis as an open letter addressed to the bishops of Gaul, Germania, Britain, and related provinces, with passages also intended for Eastern bishops (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary knew that Western Nicenes had kept apart from Eastern brethren due to three factors: ignorance of Eastern events, misunderstanding of the term homoousios, and mutual distrust (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He aimed to remedy these by explaining Eastern confessions of faith and showing that many differences were more verbal than substantive (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia). Writing as a peacemaker, he hoped to unite all who truly confessed Christ’s divinity. At the same time, Hilary did not ignore the presence of genuine heresy—he acknowledged that many Eastern bishops remained deliberately Arian, which threatened the Church’s unity (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia). Thus, Liber de Synodis was born out of a critical historical moment: the eve of the dual Councils of Rimini (West) and Seleucia (East) in 359. Hilary sought to prevent a Western-Eastern schism by clarifying the East’s “faith” for Western readers, strengthening the orthodox alliance before Emperor Constantius could impose an Arian creed (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia) (Saint Hilary of Poitiers - Bishop, Doctor of the Church, Orthodoxy - Britannica).

Key Theological Themes and Arguments

1. Survey of Eastern Creeds: A major portion of De Synodis is historical and descriptive. Hilary systematically presents and comments on the creeds from recent Eastern synods (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He transcribes their texts (often offering his own Latin translations, since existing ones were too literal and obscure (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers))) and evaluates their orthodoxy. For example, he cites the Second Sirmian formula (357) – a blatantly Arian statement he calls the Blasphemia – and then the opposing Synod of Ancyra (358) which issued 12 anathemas against that Arian creed (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Before listing Ancyra’s anathemas, Hilary pauses to define key terms: essentia and substantia. He explains that essentia (“that which is, or from which something is, subsisting in itself”) is effectively identical to substantia, since whatever truly exists must subsist of itself (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). By clarifying essentia/substantia, Hilary prepares his Latin audience to grasp Greek ousia terminology used in the Eastern creeds. He then endorses the Synod of Ancyra’s anathemas as a valid rejection of Arian error (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary proceeds chronologically: he examines the Dedication Creed of Antioch (341), noting it lacks explicit affirmation of the Son’s exact likeness to the Father but charitably explaining this was because that synod fought Sabellian (modalist) tendencies, not the extreme Arians (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He sees in its wording (e.g. “Deum de Deo, totum ex toto”) an implicit safeguard of the Son’s full divine nature (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He then reviews the “Cabal” Synod of Philippopolis (343) – a rival council of Easterners during the Council of Sardica – highlighting that its creed condemns radical Arianism and proclaims the Son “God from God” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary even interprets one anathema (against those who say the Son was begotten “without the Father’s will”) as stressing the eternal, impassible generation of the Son, not subject to fleshly passions (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Next, Hilary devotes a large section to the First Sirmian Creed (351) composed against Photinus (a heretic who denied Christ’s pre-existence). He reproduces this long formula and its 27 anathemas, approving each one, since they affirm the Son’s eternal generation and distinction from the Father without compromising His true divinity (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Throughout this survey, Hilary’s pattern is to let the Eastern texts speak, then gently correct or underscore their meaning. He emphasizes that multiple creeds arose because no single brief statement could exhaust the mystery of an infinite God – each was formulated to counter specific heresies for the sake of clarity (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Had heresy not been rampant, such repeated definitions would be unnecessary (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). This historical section demonstrates Hilary’s core argument: apart from a few “blasphemous” formulations, most Eastern synodal statements, properly understood, do not fundamentally differ from Nicene orthodoxy – the conflicts often lie in words rather than ideas (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia).

2. Trinitarian Doctrine and Hilary’s Own Confession: After surveying the synods, Hilary transitions to a theological exposition of his personal faith (chapters 64–69 of the work). Here he clearly states the Nicene Trinitarian doctrine he upholds (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He professes one God in three distinct divine Persons – explicitly rejecting Sabellian modalism (the idea of only one person in God) on one hand, and any “difference of substance” between Father and Son on the other (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He affirms the Father is greater as Father (the source), but the Son is not lesser in divine nature – a way to acknowledge the Father’s primacy of origin without subordination of essence (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary humbly admits the limitations of human language when speaking of God: if his words fall short, his intended meaning remains orthodox (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). This leads into a nuanced discussion of the contentious term ὁμοούσιος (homoousios), “of one substance.” Hilary knows this Nicene term has caused misunderstanding, so he carefully defines what it should – and should not – mean (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He outlines three erroneous interpretations of homoousios that opponents feared: (a) that it implies no personal distinction between Father and Son (a Sabellian error), (b) that it implies the Godhead’s substance is divided or separable, and (c) that it suggests Father and Son are two beings deriving from some prior common substance (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary firmly rejects all three misunderstandings. In a structured clarification, he explains the correct meaning Nicenes intend by homoousios:

- No Denial of Persons: Homoousios does not collapse Father and Son into one person. The Father is unbegotten and the source; the Son is begotten and distinct, so personal differentiation remains (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

- No Division of Essence: It does not mean the divine essence is split into parts. God’s nature is simple and indivisible, so Father and Son fully share the one indivisible divine being (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

- No “Third Thing” Preceding Father and Son: It does not mean Father and Son are two outputs of some earlier substance. Rather, homoousios means the Son derives being from the Father as His perfect Image, like Him in power, glory, and nature (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). The Father imparts His own divine nature to the Son in eternal generation, without any change or diminishment.

Understood this way, homoousios safeguards both the Son’s full divinity and the distinction of Father and Son (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary eloquently summarizes: the Son is “wholly God…Not a second God, but one God with the Father through similarity of essence” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). The Son is co-equal, not a creature, and is one in divine nature with the Father – therefore it is not an error but a necessity to confess the Son’s consubstantiality (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary even cites Scripture (e.g. John 10:30, Philippians 2:6) to reinforce that the Son is both “like God and equal to God,” for only an essential likeness justifies Christ’s claim “I and the Father are one” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Any mere similarity that falls short of true equality is inadequate, even blasphemous, because the Son’s likeness is one of nature, not an analogy or lesser resemblance (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Thus, Hilary shows that the moderate Eastern term homoiousios (“like in substance”) logically leads to and is fulfilled by homoousios (“same substance”) when rightly understood (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Rather than implying separation or rivalry between Father and Son, consubstantiality secures the true unity of God.

3. Exhortation to West and East – Reconciling Terminology: Having clarified the theology, Hilary directly addresses both Western and Eastern bishops in turn, urging reconciliation in faith. To his Western colleagues, he essentially says: do not get hung up on the word itself as long as the truth it signifies is upheld. If the Eastern confessors grant the reality of the Son’s equality, why should anyone object to the Nicene term? (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He notes the West could “retain the sound while forgetting the content” – a warning not to use homoousios as a mere slogan without understanding (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Likewise, he challenges, was the alternative term homoiousios really free of all potential misunderstanding? (Certainly not.) In fact, “really like means really equal,” Hilary argues, so if the Eastern homoiousios party truly confess an essential likeness, they in effect affirm the same truth Nicene homoousios guards (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). The two terms, properly explicated, converge on the same orthodox belief (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Therefore, Hilary counsels Western bishops to be patient and not condemn those Eastern brethren who hesitate at homoousios—their hesitation often stems from a legitimate concern to avoid Sabellianism or unscriptural language, rather than from heresy (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

Conversely, Hilary then turns to the Eastern bishops of good will (the semi-Arian or “Homoiousian” party) and beseeches them to reconsider their aversion to Nicaea (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He lavishes praise on those Eastern synods (like Ancyra) that took a stand for Christ’s true divinity, and he rejoices that even the Emperor (Constantius) had recently backed away from the worst Arian formula (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). With almost Pauline zeal, Hilary declares he would gladly remain in exile forever if truth could prevail in the Church (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He then offers fraternal correction to the Eastern letter issued from Ancyra: in that document the bishops had rejected the term homoousios outright. Hilary asks them to reflect why they rejected it (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). There are only three possible reasons to reject homoousios, he says: (a) a worry it implies a prior substratum before Father and Son; (b) an association with Paul of Samosata’s heresy (Paul had abused the term in a different sense); or (c) the complaint that the word is unscriptural (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary systematically responds: the first two objections are misunderstandings or “illusions” – Nicene usage meant neither of those things (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). The third objection (that a word is not found in Scripture) would be equally fatal to homoiousios, which also is a non-scriptural term (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). In other words, if the Eastern confessors truly mean homoiousios in the sense of an identical divine nature (as many of them did), then they actually condemn the same Arian blasphemies that the Nicenes do, and they mean the same truth, only with a different word (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Why then “decline the word which the Council of Nicaea had used for an unquestionably good end?” Hilary inserts the full text of the Nicene Creed at this point, reminding the Easterners that while homoousios can be abused or misunderstood, so can any difficult theological term or even Scripture itself, if one applies hyper-literal “word tests” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). The potential misuse of a doctrinal term does not nullify its correct use (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). The authority of the 318 bishops at Nicaea in vindicating homoousios outweighs the earlier qualms of 80 bishops at Antioch who, decades before, had objected to Paul of Samosata’s misuse of the term (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary makes a personal testimony here of great significance: before he knew the Nicene term, he already believed its truth, and once he learned it, the term only strengthened (“invigorated”) the faith he always held (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). In essence, Hilary tells the Eastern bishops (and “posterity” as well) that homoousios is truly scriptural in sense, though not in letters, because it alone adequately preserves the biblical faith in Christ’s true deity (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Thus, he implores them to “return to that faith as expressed at Nicaea” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). This impassioned appeal is one of the work’s climactic moments: East and West, he argues, have no real dogmatic disagreement—only a linguistic one that can be resolved by charitable understanding. Both homoousios and homoiousios—if used intelligently—point to the same orthodox doctrine (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Hilary’s theology throughout is firmly Nicene: the Son is fully God from God, Light from Light, begotten not made, one in essence with the Father. But his tone to the semi-Arians is conciliatory, aiming to win them, not vanquish them.

4. Opposition to Genuine Heresy: While De Synodis is irenic towards confused brethren, Hilary is unsparing toward real heretics. He condemns the Anomoeans (extreme Arians who taught the Son is unlike the Father) as emissaries of the Antichrist (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia) (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia). In an aside filled with “refined sarcasm,” he questions whether notorious Arian bishops like Valens and Ursacius were truly ignorant of homoousios’ meaning when they signed an orthodox-sounding creed only to later promote the ambiguous Dated Creed of 359 (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He strongly suspects their bad faith. Hilary also rebukes any lingering Eastern reluctance to embrace Nicaea, dismantling their rationales as shown above. In effect, he draws a sharp line: those who intelligently maintain either homoousios or homoiousios mean the same thing and jointly oppose the Arians’ impiety (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). But those who knowingly fight the Nicene truth are aligning with Antichrist, a term he does not hesitate to use for the brazen Arians attacking Christ’s divinity (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia). Earlier in the letter, Hilary had praised the Gallic bishops for condemning the “impious and infidel” creed of Sirmium as soon as it reached them (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). His own exile was a result of resisting imperial Arianizing efforts, and he remained steadfast. Thus, De Synodis combines conciliatory outreach with polemical rebuke of hardened heresy. Hilary’s overriding goal is to assist the Catholic cause and “frustrate the heretic” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) – to unify the orthodox camp in order to more effectively defeat Arianism. The letter concludes (chapter 92) with a final address to the Western bishops, modestly defending his action in writing such a treatise and urging them to show equal zeal in combating error and misunderstanding (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He ends with a devout prayer, entrusting the unity and purity of the faith to God (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

Linguistic and Textual Considerations

Language and Terminology: One of the most striking features of Liber de Synodis is its role as a linguistic bridge between Greek and Latin theological traditions. Hilary wrote in Latin to a primarily Latin-speaking episcopate, yet he was dealing with creeds originally composed in Greek. During his exile, Hilary had attained a strong grasp of Greek theological vocabulary (EarlyChurch.org.uk: Hilary of Poitiers (315 - 367)), enabling him to explain nuances that many Western bishops had found bewildering. For instance, Eastern bishops spoke of three “hypostases” in God, which a Latin reader might misinterpret as “three substances” (tritheism). Hilary likely clarified that in Greek usage hypostasis corresponds to Latin persona (Person), not substantia (Substance). Indeed, a core issue was the term homoousios itself: derived from Greek ousia (essence, being), translated into Latin as consubstantialis. Hilary carefully dissected such terms, showing how Latin essentia and substantia overlapped and how Greek ousia should be understood (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). His deliberate definitions of essentia and substantia demonstrate an acute awareness of semantic differences that had caused mistrust. By declaring that essentia “is that which is… and in that it remains, it subsists” – essentially equating it with substance – he was helping Latin ears grasp the Greek concept of one divine ousia shared by Father and Son (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

Hilary’s translations of the creeds were another important textual consideration. He notes that earlier Latin renderings of Eastern confessions were overly literal (“slavishly adhering to the original”) and hence half-unintelligible (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). So he provides fresh Latin versions that convey the sense more clearly. For example, when quoting the Antioch and Sirmium creeds, Hilary chooses Latin phrasing that illuminates the theological intent rather than simply mimicking Greek word order. This effort to faithfully, yet readably, translate Greek theological formulae was crucial for his Western readers. It reflects Hilary’s broader mission as, in the words of one historian, “the first Latin writer to introduce Greek doctrine to Western Christendom” (Saint Hilary of Poitiers - Bishop, Doctor of the Church, Orthodoxy - Britannica). In De Synodis he is essentially performing a work of interpretation and mediation, taking Eastern synodal texts and rendering their meaning in terms Western bishops (often less fluent in Greek) could understand and accept.

Textually, Liber de Synodis is structured as a long letter divided into short chapters, making it approachable as both a chronicle and a doctrinal essay. Hilary himself called it a libellus (little book or booklet) in one correspondence. The extant text, preserved in Patrologia Latina vol. 10 (cols. 479–546) (Patrologia Latina/10 - Wikisource), runs to 92 chapters. It begins with formal epistolary greetings to multiple provinces’ bishops and even the laity of one city (Toulouse) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)), underlining its broad intended circulation. After Hilary published this work, he faced some backlash, prompting him to pen an Apologetica ad reprehensores libri de synodis (Apology to the critics of the book on synods) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). This indicates the text we have was significant enough to warrant clarification and defense by Hilary shortly thereafter. In that apology (also in PL vol.10 (Patrologia Latina/10 - Wikisource)), Hilary insists he never claimed the Eastern formulations (e.g. at Ancyra) were perfect or sufficient expressions of the true faith (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). He also explains that he only mentioned homoiousios reluctantly, to communicate with those who used it (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). These textual addenda show Hilary’s sensitivity to how his words were received and underscore the careful balancing act his letter performed.

In terms of style, Hilary’s Latin in De Synodis is less convoluted than in some of his other works (like De Trinitate), likely because he aimed for broad readability. He interweaves simple declarative sections (when listing creeds or anathemas) with eloquent theological reflection and occasional rhetorical flourish. The tone shifts from didactic and calming—“do not judge before reading everything” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers))—to passionate and urgent when he calls out intransigent Arians. The letter’s dual audience (both West and East) required a careful textual strategy: Hilary explicitly signals when he is addressing one side or the other. Modern readers observe that this “double letter” format was innovative (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Passages intended for Eastern eyes are embedded in what is ostensibly a letter to Western bishops. Hilary anticipated that copies would find their way east, so he wrote with a view to pan-Christian readership. This is an early example of a theological work consciously crafted to transcend the language divide in the Church.

Lastly, from a manuscript perspective, De Synodis survived through Hilary’s collected works and was cited by later theologians, ensuring its inclusion in medieval compilations like Migne’s Patrologia Latina. The textual transmission appears reliable, though scholars note that understanding Hilary’s exact nuance sometimes requires awareness of the Greek terms behind his Latin. Fortunately, Hilary often provides those terms or explanatory glosses. His insistence that readers not “criticize his letter until they have read the whole argument” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) suggests he was keenly aware of how a single extracted sentence could be misconstrued—a lesson in careful reading that remains relevant to the text today.

Influence on Later Christian Doctrine

Liber de Synodis had both an immediate and long-term impact on Christian theology, particularly in how East and West came to a mutual understanding regarding the Trinity. In the short term, Hilary’s effort contributed to the eventual reconciliation of the semi-Arian bishops with Nicene orthodoxy. By showing that terms like homoousios did not entail Sabellian modalism and that homoiousios could be embraced in an orthodox sense, Hilary paved the way for many cautious Eastern bishops to accept the Nicene Creed. Indeed, within a few years, key leaders of the homoiousian party (such as Basil of Ancyra and others) moved closer to Nicene theology, especially after the Council of Alexandria in 362 (which, in a spirit akin to Hilary’s, declared that whether one spoke of one hypostasis or three hypostases in the Godhead, the same truth could be meant). Hilary’s bridging work likely influenced this climate of terminological reconciliation. His central conviction—that differences were often verbal, not substantive (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia)—proved true as many former “Semi-Arians” rallied to the Nicene cause once extreme Arianism (Anomoeanism) was clearly repudiated (Saint Hilary of Poitiers - Bishop, Doctor of the Church, Orthodoxy - Britannica).

In the West, Hilary’s writings solidified Nicene doctrine at a time when it was under imperial pressure. De Synodis complemented his larger doctrinal opus De Trinitate in forming a Latin theological vocabulary for the Trinity. Later Latin Fathers, most notably St. Augustine, benefited from Hilary’s pioneering work. Augustine refers to Hilary with great respect and may have drawn on some of his explanations of the Son’s equality and the Father’s monarchy when crafting his own De Trinitate decades later. Hilary was one of the first to articulate in Latin the nuanced Trinitarian theology that the Greek East had developed – this earned him the title “Doctor of the Church” much later (he was proclaimed such in 1851) (Saint Hilary of Poitiers - Bishop, Doctor of the Church, Orthodoxy - Britannica). Concepts that Hilary defended (the consubstantiality of the Son, the use of persona vs. substantia, etc.) became standard in Western orthodoxy. Even the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (381) – which became the definitive creed of Christendom – vindicated Hilary’s stance by reaffirming homoousios and expanding teaching on the Holy Spirit in a similarly Nicene way. We might say Hilary helped preserve the Nicene formula during a precarious time so that it could emerge triumphant at the Second Ecumenical Council.

Another aspect of Hilary’s influence is in the model he set for how to handle theological disagreement. His approach in De Synodis – firm on core doctrine but patient and irenic on matters of wording – can be seen as an early exercise in what we today call theological dialogue. Rather than immediately denouncing those who hesitated at an orthodox term, he tried to understand their concern and educate them, while still upholding the truth. This attitude bore fruit in the Church’s eventual healing of the Arian schism. In later centuries, churchmen dealing with East-West differences (for example, around the time of the Council of Chalcedon 451, when Greek and Latin terminology clashed over Christology) could look back to Hilary’s method as a precedent for finding common orthodoxy despite linguistic variation.

Hilary’s insistence that doctrinal terms must be explained and understood (not merely enforced by authority) is another lasting contribution. It underscores the principle that orthodoxy is rooted in meaning, not just wording (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). This insight is valuable whenever the Church encounters new languages or concepts – the underlying faith can be translated if one is careful to convey the sense. In a way, Hilary anticipated the work of later theologians who translated Christian doctrine to new cultures.

Finally, Hilary’s success in rallying the West against Arianism was directly bolstered by De Synodis. Upon his return from exile (in 360), he was hailed as a champion of the faith in Gaul (EarlyChurch.org.uk: Hilary of Poitiers (315 - 367)). The Council of Paris (361) followed his lead in condemning the Arians. His writings, circulated and read by other Latin bishops, fortified their resolve to resist any imperial creed that fell short of Nicaea. Therefore, De Synodis had a concrete effect on ecclesiastical decisions of the late 4th century. It is no surprise that St. Jerome and others remembered Hilary as “the illustrious teacher of the churches,” crediting him with defending Trinitarian doctrine in the West.

In sum, while Liber de Synodis may not be as famous as the Nicene Creed itself, its influence is seen in how it helped align Eastern and Western orthodox understanding. It stands as an early instance of inter-traditional theological mediation, whose impact is evident in the eventual unity achieved at Constantinople 381 and the subsequent transmission of Trinitarian doctrine in both Greek and Latin Christianity.

Comparison with Other Synodal Writings

Hilary’s De Synodis can be compared to several other 4th-century writings dealing with synods and creeds, highlighting its unique purpose and method. One relevant counterpart is St. Athanasius of Alexandria’s work De Synodis (also known as the Epistle On the Councils of Ariminum and Seleucia, c.359). Athanasius, the great Eastern Nicene defender, likewise compiled and analyzed various Arian and semi-Arian creeds in that treatise. However, the tone and aim differed: Athanasius’s approach was more polemical. Writing after the disastrous double-council of Rimini–Seleucia (where many orthodox bishops were coerced into a compromise creed), Athanasius used the proliferation of Arian-sponsored formulas to ridicule their inconsistency and doctrinal shallowness. He sharply denounced the successive creeds as evidence that the Arians “have no firm faith at all,” since they kept altering their confession. Hilary’s work, written slightly before those councils, was more conciliatory, emphasizing common ground with semi-Arians rather than strictly cataloguing Arian missteps. Both authors quote many of the same creeds (Sirmium, Antioch, etc.), but for Athanasius the sheer number of new creeds proved the heresy of Arianism, whereas for Hilary, those Eastern creeds – aside from the egregious ones – potentially contained or approached the truth of Nicaea when properly interpreted. In fact, Hilary’s generous reading of some formulas “would have been impossible” had he written after Rimini’s fallout (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). The timing of his letter allowed an optimism that Athanasius, writing later, did not share. Thus, De Synodis and Athanasius’s De Synodis are often seen as complementary: one seeks to win over the wavering, the other to expose the obdurate. Both, however, strongly defend Nicene theology and reject the Homoean (“like the Father”) creed that the Imperial party was touting.

Another comparison can be drawn with the writings of Lucifer of Cagliari, a Western bishop who was an ardent Nicene and a contemporary of Hilary. Lucifer, in works like Ad Constantius and others, took a hard-line stance: he refused any compromise with those who had even momentarily accepted Arianizing formulas. When Hilary circulated De Synodis, Lucifer and his allies (the Luciferians) were troubled by its moderate tone. Hilary had to reassure Lucifer that he did not endorse the term homoiousios itself, and that he only mentioned it “against his will” as a concession in dialogue (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). This exchange highlights how Hilary’s synodal treatise contrasted with other synodal responses: Lucifer wrote no conciliatory tract, but instead wrote sharp pamphlets excommunicating Arians and any who associated with them. Compared to Lucifer’s fiery synodal letters, Hilary’s Liber de Synodis appears as a model of restraint and bridge-building. The downside was that, as Hilary himself noted, it “satisfied neither the genuine Arian nor the violently orthodox” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) – extremists on both ends found fault with it. Lucifer’s faction thought Hilary too soft, whereas Arians certainly hated Hilary’s underlying Nicenism. In the spectrum of synodal writings, Hilary occupies a middle ground approach that was relatively rare at the time.

We can also consider De Synodis alongside official synodal letters of the era. For instance, the Council of Ancyra’s letter (AD 358) and the Council of Alexandria (AD 362) letter were communications aiming to unify belief. The Ancyra letter (written by Eastern semi-Arians) condemned Arian blasphemies but rejected homoousios – Hilary discussed and partly critiqued this letter in De Synodis. The Alexandria letter of 362 (penned under St. Athanasius’ guidance) reconciled those who spoke of one ousia and those who spoke of three hypostases. Hilary’s work can be seen as a forerunner to Alexandria: he anticipated the need to clarify terminology and to distinguish semantic quarrels from actual heresy. Like the Alexandrian fathers, Hilary argued that differing formulas could conceal an underlying agreement on the same orthodox faith (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Both writings share a pastoral, unifying intent. However, Hilary was writing as an individual doctor, not with conciliar authority, which perhaps allowed him more freedom to speculate and persuade.

Later synodal or conciliar documents, such as the Tome of Pope Damasus (372) or the Edict of Theodosius (380) enforcing Nicene Christianity, took a much more cut-and-dry approach: they simply affirmed Nicene theology and anathematized heresies, without the explanatory nuances Hilary employed. In comparison, Hilary’s Liber de Synodis stands out for its detailed commentary style – he doesn’t just state conclusions but walks the reader through the content of various synodal decisions. This makes it somewhat unique; most synodal writings are either creeds, canons, or brief encyclical letters, not lengthy analytical essays. In a sense, Hilary created a hybrid genre: part history, part theology, part apology.

Finally, it’s worth comparing Hilary’s treatise to the creedal statements it analyzes. Those Eastern synodal statements (from Antioch, Sirmium, etc.) were collective products, often politically influenced and sometimes deliberately ambiguous. Hilary’s commentary unmasks their meaning and measures them against the Nicene standard. He often amplifies what is merely implicit in a creed (for example, drawing out the full force of “Deus de Deo, totum ex toto” in the Antioch creed to show it implies the Son’s complete divine essence (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers))). In doing so, Hilary’s work serves almost as a hermeneutic guide to the era’s creeds. Athanasius’s De Decretis (another work) did similarly for Nicaea’s creed, explaining why homoousios was necessary. Hilary, however, ranges over multiple creeds. His willingness to interpret some non-Nicene creeds “somewhat favorably” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) – as long as they condemned Arius’ core error – is a distinguishing feature. Other orthodox writers like Athanasius were more inclined to dismiss sub-Nicene creeds outright as inadequate or even cunning. Hilary instead tried to find the orthodox intention behind those words whenever possible.

In summary, compared to other synodal writings of the 4th century, Liber de Synodis is singular in its comprehensiveness and irenic tone. Athanasius’s works share the comprehensive scope but not the gentle tone; Lucifer’s share the zeal for orthodoxy but not the willingness to dialogue; official synodal letters share the desire for unity but not the depth of explanation. Hilary’s treatise thus fills a niche: it’s a private theologian’s open letter that deeply engages with conciliar texts to mend a rift in understanding. This method would not be common until perhaps the ecumenical dialogues of much later centuries, making Hilary something of a pioneer in synodal theology-writing.

Summary of the Work and Critical Insights

Liber de Synodis seu Fide Orientalium is, in essence, St. Hilary’s theological briefing on the Eastern Church’s post-Nicene creeds, coupled with a heartfelt plea for unity in the orthodox faith. Historically, it arose from a critical juncture where misunderstandings between Greek East and Latin West threatened the Church’s cohesion. Hilary provided context and clarity, showing that the Eastern bishops’ “faith” – minus a few heretical statements – often aligned with that of Nicaea, differing more in phrasing than substance (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia). The work systematically reviews key synodal formulas of the 340s–350s, critiques Arian innovations, and robustly defends the Nicene dogma of the Trinity using Scripture and reason. Its key contributions include Hilary’s lucid explanation of homoousios, his demonstration that homoiousios (when used in good faith) leads to the same truth, and his overriding message that Church unity can be achieved if both sides understand each other’s terminology (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

Critically, one observes that Hilary was writing with a pastoral and irenic strategy. He walked a fine line between, on the one hand, fidelity to Nicene orthodoxy, and on the other, a conciliatory outreach to those wary of the Nicene formula. This strategy was not universally applauded. As Hilary himself notes (and as subsequent events confirmed), De Synodis “did not pass unchallenged” (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Rigid Nicenes like Lucifer of Cagliari felt Hilary had bent over too far to accommodate the semi-Arians, while true Arians were naturally displeased with his insistence on the Nicene truth. Hilary’s need to issue an Apology afterwards indicates that some misunderstood his intentions – perhaps misreading his sympathetic tone as endorsement of sub-par creeds. In that apology, he clarifies that citing or explaining a creed is not the same as approving it entirely (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). From a critical standpoint, this reveals the inherent risk in Hilary’s approach: by interpreting heterodox statements benevolently, one might be seen as giving them a pass. Hilary was aware of this risk and repeatedly reminded readers to consider his whole argument, not cherry-pick snippets (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). Modern scholars tend to view Liber de Synodis as a courageous and largely successful attempt at mediation, noting that Hilary’s positive influence on semi-Arians was real, even if at the time he drew some ire (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

Another insight is how De Synodis illustrates the dynamics of Church politics and theology in the 4th century. Hilary, an exiled Western bishop, uses his pen to affect ecclesial opinion across the empire – effectively countering imperial theology with reasoned argument. His work underscores that doctrinal unity in the Church was not achieved by imperial edicts, but by patient theological work and fraternal correction. Hilary’s emphasis that emperors and secular power should not determine doctrine (a theme he touches on, echoing Athanasius’s sentiments about bishops seeking worldly favor (Hilary of Poitiers - Wikipedia)) was an important principle for the Church’s self-understanding. In De Synodis, one sees an early assertion of the independence of doctrinal truth from political coercion – an idea that would echo through later Church history.

From a theological perspective, Liber de Synodis offers a rich, detailed snapshot of Trinitarian doctrine in development. Hilary’s theological acumen shines especially in the latter half, where he manages to articulate the equality of Father and Son while acknowledging the Father’s primacy as source – a balance that would become standard in later Trinitarian theology (often referred to as the doctrine of the Father’s monarchia within the Trinity). His explanation of the dangers of misreading homoousios (as implying Sabellianism, division, or a third substance) is a valuable catalog of trinitarian pitfalls to avoid (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). By ruling out those, he helps sharpen the definition of orthodoxy. It is noteworthy that Hilary was writing for an audience that had never attended Nicaea, yet by the end of the letter he has led them to essentially reaffirm Nicaea’s creed with understanding and conviction (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)). This pedagogical achievement cannot be overlooked: Hilary not only advocated for Nicene doctrine, he taught it in a way that his contemporaries could grasp and accept. In doing so, he strengthened the doctrinal foundation of the Western Church, which remained firmly Nicene thereafter.

In conclusion, Liber de Synodis is a testament to how careful theological analysis can bridge divides and combat heresy simultaneously. Hilary of Poitiers, through this comprehensive review of Eastern synodal formulae, vindicated the orthodoxy of those who shared Nicene faith under different phrases and exposed the error of those who opposed that faith. His work exhibits a rare blend of erudition, diplomatic tact, and doctrinal rigor. While not every contemporary agreed with his approach, history vindicated the substance of Hilary’s position – the Nicene creed emerged triumphant, and many who once balked at homoousios came to confess it, essentially fulfilling Hilary’s hopes. The Liber de Synodis thus stands as both a summary of a crucial theological era and a critical instrument in shaping its outcome. It remains of great interest to scholars as it preserves numerous creeds and decisions, interpreted by an eye-witness expert, and provides insight into the Church’s process of achieving doctrinal consensus. In Hilary’s own words, his aim was that “truth might be preached” even if he should remain in exile forever (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) – an expression of selfless dedication to the faith. The critical insight we gain is that sometimes, unity in truth requires patient explanation and willingness to find the common meaning behind different expressions. Hilary’s Liber de Synodis exemplifies this approach, making it not just a document of its time, but a enduring lesson in how the Church can resolve internal theological conflicts through dialogue anchored in fidelity to revealed truth.

Sources: Hilary of Poitiers, Liber de Synodis (PL 10:479–546) (Patrologia Latina/10 - Wikisource); Introduction by E. W. Watson (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)); Athanasius, De Synodis; Encyclopædia Britannica (Saint Hilary of Poitiers - Bishop, Doctor of the Church, Orthodoxy - Britannica); Early Church writings (EarlyChurch.org.uk: Hilary of Poitiers (315 - 367)); New Advent translation and notes (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)) (CHURCH FATHERS: On the Councils (St. Hilary of Poitiers)).

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube