Opusculum de vigiliis servorum Dei (c.400)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

A concise 4th-century treatise by Saint Nicetas of Remesiana defending nocturnal prayer vigils, long misattributed to other Church Fathers, that blends scriptural exhortation with pastoral sensitivity to establish night prayer as an ancient, Christ-centered spiritual discipline vital for Christian formation in newly converted communities along the Roman frontier.

Historical Context

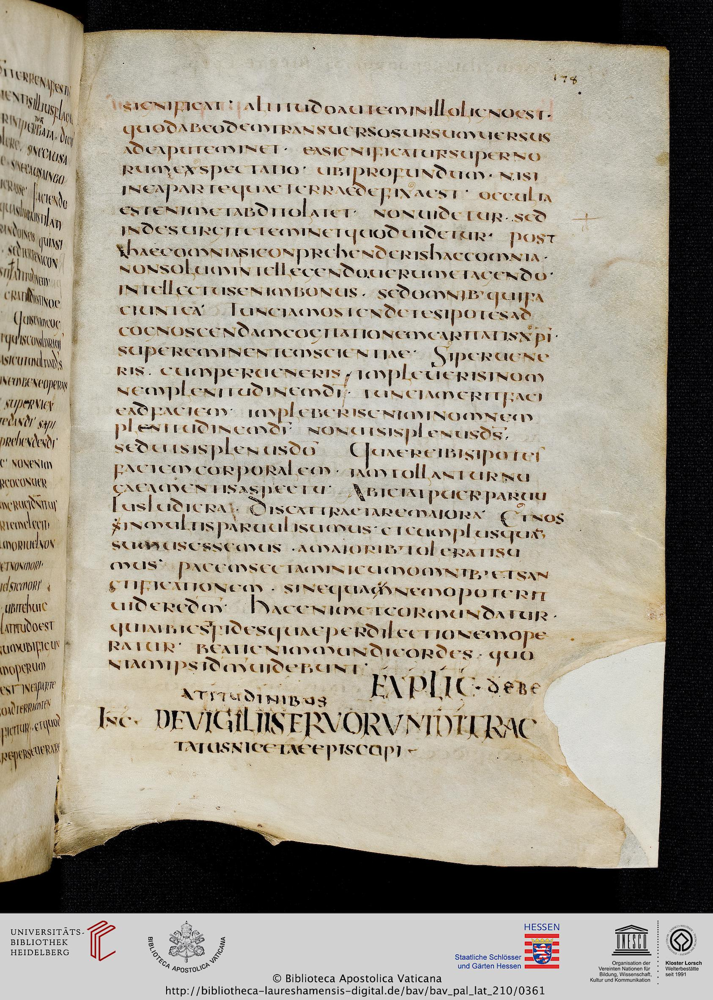

(Vatikan, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 210) (Jerome Epistulae Rare Books)

A 6th-century manuscript (Pal. lat. 210) preserves the beginning of Opusculum de vigiliis servorum Dei, explicitly attributing it to “Nicetae episcopi” (Niceta the bishop) (Jerome Epistulae). This short treatise on the “vigils of the servants of God” was long thought to be the work of Saint Nicetius of Trier (6th century). In Migne’s Patrologia Latina vol. 68 (1847), it is printed under Nicetius’s name (Patrologia Latina). Modern scholarship, however, has firmly established that the true author is Saint Nicetas (Niceta) of Remesiana, a Balkan bishop of the late 4th–early 5th century (Catholic Encyclopedia) (Encyclopedia.com).

Nicetas was a missionary bishop in the province of Dacia (present-day Serbia/Romania), a contemporary and friend of St. Paulinus of Nola (Catholic Encyclopedia). Paulinus praised Nicetas for spreading Christian faith and “melting the icy hearts” of barbarian peoples with the “sweet songs of the Cross,” indicating Nicetas’s role in introducing hymnody to new converts (Catholic Encyclopedia).

This context of early Christianization on the empire’s frontier helps explain the treatise’s purpose. It was likely written around the 390s–400s as an instructional sermon to encourage the practice of night vigils among Nicetas’s flock, at a time when all-night worship services were being introduced into local church life (Christian Mission on Romanian Territory). The author refers to the vigil service of “two nights in the week, that is, Saturday and Sunday”, recently established in the community. This suggests a monastic or ecclesial setting where weekend nocturnal vigils (Friday night to Saturday, and Saturday night to Sunday) were a new devotional innovation. Indeed, Nicetas appears as a “keeper of the cultic tradition” in adapting the wider Church’s liturgical practices (likely inspired by Eastern monastic vigils and the growing Western custom of Saturday night vigils) to his Dacian congregation.

The treatise’s historical backdrop also involves pastoral challenges. Nicetas acknowledges that some Christians found the vigil observances “superfluous…useless…or worse, burdensome” (Epistolae - Wikisource). He writes to defend and normalize the vigil practice, addressing objections from the lazy, the sleepy, or the infirm. This indicates a local controversy or hesitancy toward night-long worship: perhaps older customs did not include late-night church gatherings, and Nicetas had to persuade the faithful of their value. He carefully exempts the elderly and sick from any strict obligation, yet urges them not to discourage the young and strong who “ought to mortify themselves with more ardent vigils” as a remedy against youthful temptations.

Thus, the Opusculum is situated in a period of liturgical development and ascetic enthusiasm in the late 4th century. It reflects the spread of monastic spirituality (vigils, psalmody, fasting) into the broader Church, even in frontier regions. Authorship by Nicetas of Remesiana also places it amidst the final struggles against Arianism and paganism in the Balkans – Nicetas was solidly Nicene in theology (Encyclopedia.com) and an energetic evangelist. In summary, the historical context is one of early Christian practice being solidified, with Nicetas advocating regular weekend vigils as a means to deepen the faith and discipline of a newly converted people.

Theological and Spiritual Significance

The Opusculum de vigiliis servorum Dei is rich in theological and spiritual themes centered on the value of nocturnal prayer. Its key concern is to exhort Christians to watchful prayer as a form of spiritual discipline and devotion. Drawing on a broad sweep of Scripture, the author argues that keeping vigil through the night is a holy practice with deep biblical roots and profound spiritual benefits.

For example, he reminds readers that the prophet Isaiah prayed “O God, my spirit keeps vigil for You in the night” (Isa. 26:9) and that King David likewise sang, “By day I cried out, and by night before You” (Ps. 87:2) (Epistolae - Wikisource). Such verses are used to establish the ancient authority and precedent for vigils: “The devotion of vigils is ancient, a familiar good to all the saints”, Nicetas writes, calling it “antiqua…familiare bonum omnibus sanctis”.

He emphasizes that God’s people have always prayed at night, whether in the Old Testament (patriarchs, prophets, psalmists) or in the New. He cites the Gospel example of the aged Anna, who “did not depart from the Temple, worshiping with fasting and prayer night and day” (Luke 2:37), and the Bethlehem shepherds who were granted angelic visions “while keeping night watches over their flocks” (Luke 2:8-14). These examples underscore a theological point: vigil-keeping is pleasing to God and often attended by divine grace or revelation.

A strong Christological and eschatological motif runs through the work. Nicetas invokes Jesus’ own teaching and example to highlight the spiritual meaning of vigils. Christ’s parable of the enemy sowing weeds “while men slept” is referenced as a warning that spiritual slumber allows the Devil’s work. In contrast, Jesus exhorts, “Let your loins be girded and your lamps burning… Blessed are those servants whom the Lord finds watching when He comes” (Luke 12:35-37). This is a direct theological link between vigilance in prayer and readiness for Christ’s coming.

The treatise thus casts the night vigil as a symbol of spiritual watchfulness in expectation of the Lord – an active living out of the Gospel injunction to “watch and pray” (Mark 14:38) so as to persevere against temptation. Moreover, the author notes that Jesus Himself “spent the whole night in prayer to God” (Luke 6:12). If Christ – who had no need of help – prayed through the night, how much more should we, “poor and weak servants,” do so for our spiritual welfare.

By pointing to Jesus’ vigil in Gethsemane and His gentle rebuke to the drowsy apostles (“Could you not watch one hour with me?”), the treatise presents night vigil as a way of sharing in Christ’s own prayer and passion. It is a means to “watch with” Jesus, expressing love and solidarity with Him. This christocentric emphasis gives the practice a deeply devotional and relational character: the faithful keep vigil out of love for Christ and desire to imitate Him. At the same time, it has an eschatological edge – staying spiritually awake for the coming Judgment, like the wise virgins with lamps alight, a parable Nicetas alludes to explicitly.

Spiritually, Nicetas highlights numerous beneficial effects of vigils. In one eloquent passage, he catalogues the fruits borne in the soul that practices nocturnal prayer:

“By keeping vigil, all fear is cast out, confidence is born; the flesh is mortified, vices waste away; charity is strengthened, folly departs, wisdom approaches. The mind is sharpened, error is driven off, and the Devil – author of sin – is wounded by the sword of the Spirit.” (Epistolae - Wikisource)

This litany of spiritual gains reflects the treatise’s ascetical theology. Night vigils, as a form of self-denial (sacrificing sleep), help purify the soul: they subdue the body’s impulses and foster virtues like courage, prudence, and fervent love of God. In Nicetas’s view, the silence and stillness of night provide an ideal context for prayer, free from daytime distractions: “Night, quiet and secret, offers itself to those praying, most suitable for those watching”, whereas by day “various cares and occupations distract the mind” (Epistolae - Wikisource).

This reflects a mystical insight common in early monastic literature – that the night hours are especially sacred and conducive to encountering God. The treatise even asserts that one must “taste” this practice to truly understand its sweetness, echoing “Taste and see that the Lord is sweet” (Ps. 34:8) (Epistolae - Wikisource).

In theological terms, vigils are presented as a sacrifice of praise (cf. Heb. 13:15) offered at a time when nature sleeps – an act of extra devotion that God rewards with grace and “visitation [that] gladdens all one’s members”. There is also an element of spiritual warfare: by denying themselves sleep for prayer, Christians snatch the night from the Devil’s domain. Nicetas notes that the Devil tries to ape this holy practice by inspiring his followers (in pagan revels or sinful pursuits) to hold “nocturnal feasts and carousals”, a counterfeit “vigil” in service of vice (Epistolae - Wikisource). This contrast elevates true vigils as weapons against evil – times when faithful souls, armed with prayer and psalms, do battle against sin and Satan.

Overall, the theological vision of the work is that vigil prayer is a powerful means of sanctification. It unites the Church more deeply to God in love and alertness, fulfills biblical exhortations, and prepares the soul for eternal daybreak. The treatise’s stress on interior disposition – “he who keeps vigil with the eyes, let him keep vigil also in heart” (Epistolae - Wikisource) – further underscores that the ultimate goal is vigilantia of the soul: constant faith and attunement to God’s will. In summary, Nicetas imbues the practice of vigils with rich doctrinal meaning, connecting it to salvation history (both past exemplars and future hope) and to the believer’s ongoing growth in holiness and virtue through prayerful self-discipline.

Literary and Stylistic Features

De vigiliis servorum Dei is composed in the form of a short treatise or sermon, structured as a reasoned exhortation. The style is clear, pastoral, and scripturally saturated. Gennadius of Marseille, a 5th-century bibliographer, praised Nicetas’s writings for their “simple and lucid eloquence (simplici et nitido sermone)” (Catholic Encyclopedia), and this piece reflects that characterization.

It is organized into a coherent progression of ideas. The text (as edited in modern editions) can be divided into roughly nine to eleven sections or chapters (Christian Mission on Romanian Territory). It begins with an introduction (cap. I–IV) addressing potential critics of vigils and rebutting their excuses (e.g. condemning laziness, urging the sleepy to wake, excusing the infirm but telling them not to disparage others) (Epistolae - Wikisource). This section is notable for its direct address to “brethren” (fratres) and its use of vivid rhetorical devices.

For instance, Nicetas uses rhetorical questions – “Who would not marvel at such love of God…?” – and exclamations to provoke reflection. He also employs classical analogy: “Go to the ant, O sluggard” (Prov 6:6) is invoked to shame the lazy Christian who will not spend even a portion of two nights for God (Epistolae - Wikisource). An almost humorous tone enters when he paints the picture of a drowsy person: “How long will you sleep, O sluggard?… A little sleep, a little slumber… and poverty will come upon you” (Prov 6:9-11) (Epistolae - Wikisource). By quoting these proverbs, he gently mocks the somniculosi (sleepyheads) in the congregation, prodding them with Scriptural wit. Such touches show Nicetas’s skill in engaging his audience with familiar Biblical sententiae.

The middle sections (cap. V–VIII) are didactic, piling up authorities and examples to support the practice of vigils. Here the structure becomes a catalog of testimonies: first Old Testament voices (Isaiah, David, the Psalmist) praising night prayer (Epistolae - Wikisource), then New Testament figures (Anna, the shepherds, Christ, the apostles) (Epistolae - Wikisource). The author’s language is highly Biblical, weaving direct quotations and allusions seamlessly into his own prose. He often does not explicitly mention the source, expecting a biblically literate audience to recognize lines from the Psalms or Gospels.

For example, without preamble he quotes, “Media nocte surgebam ut confiterer tibi” – “At midnight I arose to give thanks to You” (Ps. 118/119:62) – to illustrate the proper time of vigil (Epistolae - Wikisource). This intertextual style creates a homiletic tone, as if the preacher is expositing a chain of Scripture to make his point. Indeed, the work reads much like a written sermon prepared by a bishop for his congregation’s instruction. It has the flow of a homily: opening moral exhortation, a body of teaching with examples, and a concluding application.

Throughout, Nicetas uses rhetorical repetition and parallelism for emphasis. In the section praising the benefits of vigils (often considered cap. IX), nearly every sentence begins with “Vigilando…” or ends with “…atur”, as he enumerates effect after effect in a rolling cadence (Epistolae - Wikisource). This anaphora and rhythmic balance would have made the text memorable and forceful if delivered orally. There is also elegant symmetry in contrasting clauses – e.g., “as being ashamed in doing good is a sin, so not being ashamed in doing evil is ruin” (Epistolae - Wikisource). Such antitheses reflect classical influence on Christian rhetoric, yet the language remains plain and accessible, not florid.

The vocabulary is largely common Christian Latin; aside from a few rare words (e.g. lucubratio for nightly labor (Epistolae - Wikisource)), it avoids high eloquence in favor of straightforward expression.

Notably, Nicetas injects figurative sayings and maxims to spice the discourse. One striking example is a quote he attributes to “a certain distinguished pastor”: “As smoke drives away bees, so undigested belching drives away the gifts of the Holy Spirit.” (Epistolae - Wikisource). This earthy metaphor comes in the context of advising moderation in food before a vigil (so one does not fall asleep or dishonor the prayer with indigestion) (Epistolae - Wikisource). The inclusion of this proverbial wisdom – likely borrowed from earlier monastic teaching – lends a monastic gnomic element to the style, aligning with the practical, moral focus of the work.

In the closing (cap. X–XI), the tone becomes warmly exhortative again, returning to direct address: “Therefore, dearest brothers, he who keeps vigil with the eyes, let him keep vigil also with the heart… Let the heart of those who keep vigil be closed to the devil and open to Christ!” (Epistolae - Wikisource). The very final lines briefly recapitulate the treatise’s three themes – the authority, antiquity, and usefulness of vigils – and then impart a Pauline blessing: “May the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you all. Amen.” (Epistolae - Wikisource). This ending formula reinforces that the piece is meant as a pastoral address to a Christian assembly.

In sum, the literary character of De vigiliis servorum Dei is that of a scripturally-grounded exhortation, logically ordered and enhanced by classical rhetoric and monastic wisdom. Its clear structure and lively style would have made it an effective catechesis on vigils for Nicetas’s community, and indeed it remains a fine example of late antique Latin preaching in written form.

Reception History

10th-century illumination from the Egbert Psalter showing Saint Nicetius of Trier, to whom Nicetas’s treatise on vigils was long misattributed. (Egbert-Psalter, fol. 99r)

The Opusculum de vigiliis servorum Dei has an unusual transmission history marked by centuries of misattribution, followed by modern rediscovery. After Nicetas of Remesiana’s era, his works faded into obscurity and were often copied under different names (Journal of Theological Studies). By the early Middle Ages, the treatise on vigils was circulating anonymously or attributed to better-known Church Fathers.

Medieval manuscript catalogs list it as a work of “Nicetius”, which led scholars to assume Nicetius of Trier was the author (hence Migne’s 19th-century inclusion under Nicetius Trevirensis) (Catholic Encyclopedia). In at least one Frankish manuscript, it was even transmitted as a spurious piece of St. Jerome – titled Epistola XXXI de observatione vigiliarum in Jerome’s correspondence (Patrologia Latina). Indeed, De vigiliis servorum Dei appears as Jerome’s letter in Patrologia Latina vol. 30 (cols. 232–239), showing how thoroughly its true origin was forgotten. Other copies ascribed it to Augustine under the title De sanctis vigiliis (Jerome Epistulae).

This confusion persisted until scholars of the 17th century and later took interest in the text’s real provenance. The Maurist scholar Luc d’Achéry in 1659 suspected that the vigils and psalmody treatises belonged to Nicetas of Remesiana (Encyclopedia.com). Solid proof came with Dom Germain Morin in 1897, who published research and a critical edition that definitively credited Niceta of Remesiana as the author (Catholic Encyclopedia). Morin showed that early manuscripts (like the 7th-century Palatine MS) clearly named Niceta as author (Journal of Theological Studies), and that the content and style fit Nicetas’s context, not Nicetius of Trier’s. Since then, patrologists have accepted Nicetas’s authorship, and modern translations (e.g. in The Fathers of the Church series) present “The Vigils of the Saints” as Niceta’s work (The Fathers of the Church).

In terms of reception in Christian literature, the treatise’s direct influence is hard to trace under its true author’s name – precisely because it was read under pseudo-epigraphic identities. However, we can infer its impact in a few ways. First, as part of the broader monastic tradition, its ideas resonated with and perhaps subtly informed other writings on vigils. For instance, its emphasis on midnight praise and the benefits of nocturnal prayer find parallels in the writings of St. Ambrose, St. Jerome, John Cassian, and later the Rule of St. Benedict (c. 530) which formalized the Night Office (Matins) in monastic life.

It’s notable that the Rule of Benedict, composed a century after Nicetas, prescribes early morning vigils and is cognizant of human limits (shortening the vigil psalmody in summer, etc.) – concerns similar to Nicetas’s pastoral leniency for the weak. Whether Benedict knew Nicetas’s treatise is unknown, but both drew on a common ascetic consensus about the value of keeping vigil.

Meanwhile, the misattributed Epistula de vigiliis under Jerome’s name was included in collections of Jerome’s guidance to ascetics, and thus later medieval readers may have absorbed Nicetas’s counsel as if it were Jerome’s. For example, a 15th-century monastic anthology from Germany contains the “Epistle on Vigils” attributed to Jerome, placed alongside genuine letters instructing clergy (Jerome Epistulae). This shows the work was read in monastic circles as a useful exhortation on liturgical piety. The high esteem of its supposed authors (Jerome, Augustine, Nicetius) likely facilitated its copying and preservation through the medieval period.

Interestingly, Nicetius of Trier’s own legacy as a saint may have been augmented by possession of these texts. In the 10th-century Egbert Psalter, Saint Nicetius of Trier is honored with an illumination (see image) and likely revered for his wisdom (Egbert-Psalter). It is tempting to think that treatises like De vigiliis and De psalmodiae bono, long credited to him, enhanced his reputation as a teacher of prayer and chant.

Later historians noticed inconsistencies, and by the Enlightenment era some doubted Nicetius of Trier’s authorship. It was only with the critical work of scholars like A. E. Burn (who published Niceta of Remesiana: His Life and Works in 1905) that Nicetas’s oeuvre was fully reconstructed (Catholic Encyclopedia). Today, Opusculum de vigiliis servorum Dei is appreciated as part of Nicetas of Remesiana’s corpus, alongside his companion sermon De psalmodiae bono (“On the Benefit of Psalmody”).

Together, these two treatises shed light on the liturgical developments of the 4th-century Latin Church – particularly the introduction of hymn-singing and vigil services, practices also promoted by contemporaries like St. Ambrose in the West and the desert monks in the East. Modern scholars cite De vigiliis when studying the history of the Divine Office and vigil practices. For example, it is noted as evidence that Friday-night vigils (in addition to Saturday-night) were observed in some regions, as Nicetas explicitly mentions Friday and Saturday night devotion (Christian Mission on Romanian Territory).

The treatise is also referenced in discussions of the theology of leisure and labor in worship – Nicetas makes the striking argument that if people willingly toil at night for worldly gain or craft (like the industrious woman of Proverbs who works by lamplight), how much more fitting to labor in holy vigils for spiritual gain (Epistolae - Wikisource). Such insights have been noted by liturgical historians illustrating early Christian attitudes toward worship.

In conclusion, Opusculum de vigiliis servorum Dei had a quiet but persistent afterlife. Through misidentifications, it still transmitted its core message of fervent nocturnal prayer to generations of monks and clergy. Its reattribution to Nicetas of Remesiana in modern times has restored it to its proper context, allowing us to see it as a product of a frontier bishop’s pastoral zeal in the post-Nicene era. It now holds a respected place in patristic literature as an important witness to early Western vigil practices and as a testament to the spiritual ethos of early Christian monasticism spreading beyond the Roman heartlands.

Conclusion

The Opusculum de vigiliis servorum Dei is a valuable little gem of patristic literature, blending historical, theological, and spiritual dimensions. Born in the late 4th century from the pen of St. Nicetas of Remesiana, it addressed the practical challenge of instituting night vigils among new Christian communities, situating this practice firmly on biblical and theological foundations. The treatise celebrates vigils as an ancient and holy tradition, “a familiar good to all the saints”, and articulates a robust spirituality of watchful prayer – one that balances zeal with pastoral wisdom.

Literarily, it stands out for its clarity, abundant scriptural resonance, and rhetorical vigor, characteristics that made it effective in its day and readable in ours. Over the centuries, it traveled under others’ names but continued to edify those pursuing a life of prayer. Today, restored to Nicetas, it enriches our understanding of early Christian worship and ascetic piety. In it we hear the echo of the early Church’s night singers, keeping vigil for the dawn of the Kingdom – an echo that invites us, too, to embrace the call of Christ: “Stay awake and pray.” (Epistolae - Wikisource)

Sources: The Latin text is in Patrologia Latina 68, cols. 365–372 (as Nicetius of Trier) and also in PL 30, cols. 232–239 (as pseudo-Jerome). Modern editions by C.H. Turner are available in JTS 22 (1921) and 24 (1923). See A.E. Burn, Niceta of Remesiana: His Life and Works (1905), and recent overviews in the Encyclopedia of Early Christianity. The English translation “The Vigils of the Saints” is in Niceta of Remesiana: Writings (Fathers of the Church vol. 7, 1949).

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube