Libellus emendationis (c. 418)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

The Libellus emendationis, written by the Gallic monk Leporius around 418 AD, represents a pivotal theological self-retraction that addresses early Christological controversies. Under Augustine's guidance, this confession recants proto-Nestorian views on Christ's nature and anticipates orthodox formulations on the incarnation, making it a significant bridge between Western and Eastern theological developments before the Council of Chalcedon.

Historical Context and Dating

The Libellus emendationis (“Little Book of Correction”) was written in the early 5th century, against the backdrop of intense theological controversies in the Latin West. Its author, Leporius, was a monk from Gaul who fell under suspicion for unorthodox teachings and was rebuked by his superiors (likely around 417 AD) (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). Excommunicated in Gaul for teaching Pelagian ideas (denying the necessity of divine grace) and a Christology verging on Adoptionism (holding that Christ “was born with a human nature only,” not as God) (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia) (Letters), Leporius sought refuge in North Africa. There, circa 418 AD, he came under the guidance of Bishop Aurelius of Carthage and the famed theologian Augustine of Hippo, who were then combating Pelagianism. In this context Leporius underwent a dramatic change of heart. He composed the Libellus emendationis as a formal recantation and confession of faith, addressing it to his former Gallic bishops, Proculus of Marseille and Cyllinius of Aix, and explicitly dating it to his time in Carthage (c. 418) (Letters) (Letters). Contemporary records confirm that by 418 Leporius publicly confessed his error before the African church (Letters), and shortly thereafter he was reconciled. In 425 he was even ordained a presbyter by Augustine (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia), indicating the success of his rehabilitation. Thus, the Libellus is firmly situated around 418 AD, in the aftermath of the Pelagian controversy (the Council of Carthage in 418 condemned Pelagian doctrines) and just a decade before the Nestorian controversy would erupt in the East.

Authorship and Scholarly Debates

Leporius is traditionally acknowledged as the author of the Libellus emendationis, though he likely received significant input from Augustine and other African bishops. In the text’s own preface, Leporius humbly accuses himself of error and submits to correction by his “holy bishops,” implying that his confession was guided by their instruction (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource) (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). Indeed, modern scholars note that the corrected theology Leporius professes is articulated in an “Augustinian dialect” (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). It is very plausible that Augustine (and others like Aurelius) helped Leporius formulate the document’s orthodox statements (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). An early scholarly debate on authorship was raised by the 17th-century scholar Pasquier Quesnel, who hypothesized that the Libellus might actually have been drafted or dictated by St. Augustine himself (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). Quesnel pointed to the polished Latin style and the way the text is cited in later church documents as evidence of Augustine’s hand (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). However, this theory has been largely rejected by subsequent scholarship. While Augustine’s influence is undoubted, the consensus is that the work represents Leporius’s own confession, written in first person and bearing his signature, albeit under Augustine’s tutelage (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). Supporting this, the African bishops explicitly refer to it as a document “dictated by [Leporius’s] sense” and subscribed by him in their presence (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). They appended their signatures to attest its authenticity and Leporius’s sincere authorship (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). Thus, the Libellus is best seen as Leporius’s work – a genuine self-retraction – produced with pastoral oversight.

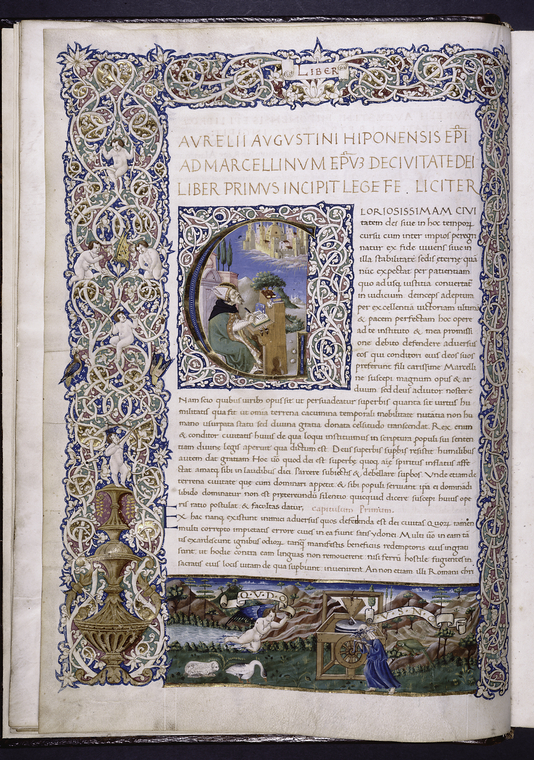

A medieval illuminated manuscript shows St. Augustine writing in his study (from a 15th-century Italian copy of his *City of God). Augustine’s guidance was instrumental in the composition of Leporius’s Libellus, though the work is ultimately attributed to Leporius himself (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia) (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW).*

It should be noted that modern scholarship uniformly affirms Leporius’s authorship while acknowledging Augustine’s role. For example, Gennadius of Marseille (a contemporary of the next generation) wrote that “Leporius, first a monk and later a presbyter, began by teaching Pelagianism and added to that various errors in Christology,” but that he “publicly corrected them” (Letters). This indicates the early Church itself viewed the Libellus as Leporius’s personal recantation. Recent studies (such as those by F. De Beer and others) have analyzed the text as a “tessera of orthodoxy” – a token of restored orthodoxy in the West on the eve of the Nestorian debates ([PDF] Tajemnica wcielenia w galijskiej literaturze V wieku na przykładzie …). In summary, there is little doubt that the Libellus was authored (and signed) by Leporius, with the authority of Augustine and the African bishops behind him, lending the work its weight and elegant theological clarity.

Summary of Content and Theological Themes

The Libellus emendationis itself is a brief but rich document, both biographical and doctrinal. In form, it is an open letter of apology and confession addressed to the Gallic bishops who had condemned Leporius. Leporius opens with heartfelt contrition, declaring that he now stands as his own accuser and “acknowledges [his] offense” (delictum) (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). He admits that through “ignorant zeal not according to knowledge” he fell into serious error, but by God’s mercy and the Church’s guidance he has been brought back to the “right path” (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). This penitential prologue sets a tone of humility and submission to authority.

The core of the document then systematically repudiates Leporius’s former heretical assertions and proclaims orthodox doctrine. First, on the matter of grace and free will, Leporius retracts the Pelagian-like idea that humans do not need divine grace. He confesses that such a view was wrong and affirms that any good in him is due to God’s grace, not his own merit – aligning with St. Augustine’s teaching against Pelagius. This section is relatively brief (since the main focus is Christology), but it is clear that Leporius now “detests” his prior presumption of self-sufficiency, invoking the authority of the Church’s regula veritatis (rule of truth) that he had exceeded (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource) (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource).

The Christological confession is the centerpiece. Earlier, Leporius had taught that “Christ was born a man and only *later became God”, effectively denying that the divine Word was truly incarnate from conception (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). He was reluctant to say *“God was born of a woman”, fearing this would imply change or suffering in God (Letters). In the Libellus, Leporius emphatically corrects this error. He now professes that the Word (the Son of God) became truly man without ceasing to be God, and that this union of divinity and humanity occurred from the moment of Christ’s conception and birth (Letters). He stresses that saying “God was born of the Virgin” is not blasphemy but the heart of the true faith, since the Word made flesh did not undergo change or lose divine status by this act (Letters). To the contrary, “no change or corruption is possible in God”, so the Incarnation is a mystery of union without alteration (Letters). In making this point, Leporius anticipates the classic formulation of one divine Person in two natures. He explicitly rejects the idea that he had introduced any “fourth person” into the Trinity – an error his former view implied by positing a separate human person of Christ (Letters) (Letters). Instead, he now teaches that Christ is one person (una persona), the Son of God, who assumed a complete human nature while remaining fully divine (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). This una persona – duae naturae understanding (one person, two natures) is remarkably in line with the Christological orthodoxy that would later be defined at Chalcedon (451). The Libellus thus contains a concise Christological creed, affirming the Virgin Birth, the title of Theotokos (implied by acknowledging Mary bore God in the flesh), and the unity of Christ’s person.

Throughout the text, Leporius often quotes or alludes to Scripture and orthodox formulae to underscore his points. He cites John 1:1 and 1:14 (“In the beginning was the Word… and the Word became flesh”) to ground the Incarnation, and he invokes Paul’s warnings against false gospels to justify the Church’s prior rebuke of him (Letters) (Letters). He then solemnly anathematizes his own former propositions. For example, he asks that the scandalous letter he once wrote be “trampled to obliteration” and entirely abolished (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). With each retracted statement, he follows with its orthodox replacement.

Finally, the Libellus concludes with Leporius’s declaration of full communion with the Catholic faith. He professes to hold and accept “all the doctrines as the order of the Catholic Church maintains” (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). He names no specific heresy or council, but clearly he aligns himself with the anti-Pelagian and anti-Adoptionist positions of the African bishops. In a gesture of obedience, he refers all his writings to the judgment of his readers’ authority, asking them to pardon his past and pray for him (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource) (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). In sum, the content moves from personal remorse to doctrinal clarity: grace is necessary, Christ is true God and true man in one person, and any teaching contrary to these (like his old views) is to be condemned. This combination of personal and theological makes the Libellus a unique document – essentially a written self-retraction serving also as a concise theological tract against two major heresies.

Connections to Contemporary and Later Theological Debates

Because it addresses key issues of sin, grace, and the Incarnation, Leporius’s Libellus is tightly interwoven with the theological battles of its era. In confessing the need for grace, Leporius directly engages the Pelagian controversy. Pelagius and his followers (active 410s–420s) denied original sin’s effect and insisted on human self-sufficiency in doing good. Leporius had embraced an extreme form of this error, “advancing the view that man did not need divine grace” (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). By 418, the Council of Carthage had anathematized Pelagian teachings, and Augustine was penning treatises on grace. Leporius’s public recantation came at precisely this time. He explicitly submits to Augustine’s doctrine by acknowledging his absolute dependence on God’s mercy (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). In doing so, his Libellus became one more witness to the victory of Augustinian theology over Pelagianism in North Africa. It demonstrated the Church’s pastoral approach: error was condemned, but a repentant teacher could be restored if he affirmed the orthodox position on grace. Thus, Leporius’s case reinforced the emerging Augustinian consensus on grace that would shape Western theology.

Even more significantly, the Libellus emendationis has a prominent place in the Christological debates of the 5th century. Scholars have often described Leporius as a “crypto-Pelagian, proto-Nestorian” figure (2 Leporius: A Crypto-‘Pelagian’, Proto-‘Nestorian’? - Oxford Academic). That is, his initial errors foreshadowed, in the West, the positions later identified with Nestorius in the East. Nestorius, as Patriarch of Constantinople in the late 420s, similarly balked at calling Mary Theotokos and seemed to divide Christ’s divinity from his humanity. Remarkably, Leporius had articulated a nearly identical concern a decade earlier – “in order to keep God from ‘things beneath him’, [he insisted] that Jesus was a ‘man born with God, but not as God’” (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). This is essentially the Nestorian error: separating the two natures of Christ so sharply as to make two subjects (effectively two “Sons”). Leporius’s conversion therefore came at a providential time. Under Augustine’s tutelage, he ended up formulating a refutation of Nestorian logic well before Nestorius was condemned. In the Libellus, Leporius powerfully argues that one can and must say God was born and suffered in the flesh, without impugning divine impassibility (Letters). He uses what later theologians would call the “communication of idioms” (attributing human experiences to the divine person of Christ) to safeguard the single personhood of Christ.

It is no surprise, then, that Leporius’s statement was later regarded as an important Western testimony against Nestorianism. In 430, when St. John Cassian wrote De Incarnatione to oppose Nestorius, he explicitly cited Leporius as an example of a man who had once erred in the same way but repented (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW) (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). Cassian even quotes from the Libellus emendationis at the beginning of his treatise (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW), using Leporius’s orthodox assertions (e.g. that “the Word became man without ceasing to be God”) as a foundation for his own anti-Nestorian arguments. In doing so, Cassian “depicted Leporius as a kind of anticipatory foe of Nestorius,” who provided the technical Christological categories needed to rebut Nestorius (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). This shows the Libellus had immediate impact: it equipped Western theologians on the eve of the Council of Ephesus (431) with a clear articulation of the faith. In fact, at the Council of Ephesus, Nestorius was condemned, and one of the charges against him – refusing to call Mary Mother of God – was exactly what Leporius had earlier recanted (Grace and the Humanity of Christ According to St Vincent of Lérins). The African Church’s handling of Leporius may have even influenced how the broader Church approached Nestorius: with a combination of stern doctrinal clarity and the hope of the heretic’s recantation (which, in Nestorius’s case, tragically did not occur).

Late medieval memory of doctrinal controversy: a 16th-century Russian fresco depicts the Council of Ephesus (431) condemning Nestorius (shown being defrocked by the bishops). Leporius’s Libellus anticipated the Council’s anti-Nestorian Christology by affirming Christ’s single person and Mary’s status as Mother of God (Letters) (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW).

Furthermore, the Libellus emendationis has connections to later Western doctrinal development. It was highly valued by theologians like St. Leo the Great (mid-5th century). Pope Leo, who fought Eutychianism and Nestorianism, likely knew of Leporius’s confession. In one of Leo’s letters, he echoes phrases found in the Libellus, suggesting he viewed Leporius’s formulation as a useful precedent (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia) (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). By the time of the Council of Chalcedon (451), the formula of “one person, two natures” was enshrined, and later records show the Libellus was remembered as an orthodox touchstone. A 6th-century writer, Facundus of Hermiane, cites Leporius when defending the unity of Christ (Full text of “Sacris Erudiri A Journal of Late Antique and Medieval Christianity”). The fact that Leporius – once a heretic – came to be lauded as “one of the firmest bulwarks of orthodoxy against the Nestorians” is a striking turnabout (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). His journey from error to truth thus not only impacted his contemporaries but also fed into the ongoing stream of Christological orthodoxy in the Church.

Manuscript History and Patrologia Latina Edition

The text of the Libellus emendationis survived in a somewhat roundabout way. After Leporius’s lifetime, his confession was preserved by admirers as evidence of doctrinal triumph. Fragments of the Libellus were known in antiquity through Cassian’s quotations (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). For centuries, however, the full text was not widely circulated on its own. It likely traveled as part of collections of letters or conciliar documents. By the early Middle Ages, references to Leporius appear in compilations of heresies (e.g. Isidore of Seville briefly notes Leporius’s error and correction) and in the works of medieval historians who had access to archives.

The rediscovery of the complete text came in the early modern period. In 1630, the Jesuit scholar Jacques Sirmond published the Libellus for the first time in full (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). Sirmond found a manuscript (or manuscripts) containing Leporius’s work – notably one in the library of Reims (France) – and recognized its importance ([PDF] Augustine-Letters-211-270.pdf - Wesley Scholar). He initially identified fragments from Cassian, then soon located an entire copy, which he included (with a Latin introduction) in Opuscula Dogmatica Veterum Quinque Scriptorum (Paris, 1630) (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). Sirmond’s edition also preserved the accompanying letter of the African bishops that authenticate the Libellus (sometimes titled Epistola Episcoporum Africae de Leporio). After Sirmond, the text was reprinted in other collections: the Labbé and Cossart Council collections (1671), an edition of Marius Mercator’s works by Garnier (1673), the Bibliotheca Patrum (1677), and Gallandi’s Bibliotheca Veterum Patrum (1773) (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). Each of these helped transmit Leporius’s confession to modern scholars. By the 19th century, the text was well established as part of the Western patristic corpus.

The inclusion of the Libellus emendationis in J.-P. Migne’s Patrologia Latina (PL) cemented its accessibility. Migne placed it in Volume 31 of the PL (published 1846), collating earlier editions (Patrologia Latina/31 - Wikisource). In PL 31, the Libellus spans columns 1221C–1230C, immediately followed by the African bishops’ letter at cols. 1231A–1232C (Patrologia Latina/31 - Wikisource). Migne drew primarily on Gallandi’s text and perhaps cross-checked Sirmond’s version, but he did not provide a critical apparatus (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). The Patrologia Latina presentation, while not critically edited, gave the work wide distribution in theological libraries and remains a standard reference (the PL citation is often given in scholarship (Letters)).

In terms of manuscript evidence, only a few copies of Leporius’s text are known due to its relative brevity and specialized nature. Manuscripts of St. Augustine’s letters include the African bishops’ epistle (which Augustine numbered as Epistle 219 in some collections) that references the Libellus (Letters). The Libellus itself was copied in some medieval compendia of theological documents. For example, a 12th-century manuscript from Saint-Rémi of Reims contained Leporius’s Libellus along with other letters (Notes antiques au De Civitate Dei de Saint Augustin dans un …). Modern critical work has identified about half a dozen manuscript witnesses. On this basis, a critical edition was produced in the Corpus Christianorum series (CCSL 64) by R. Demeulenaere in 1985 ([PDF] SALVATI PER GESÙ, MORTO E RISORTO - Teologia Verona) (List of editiones principes in Latin - Wikipedia). This edition provides scholarly apparatus and confirms the text as essentially stable since Sirmond’s discovery.

As it appears in Patrologia Latina vol. 31, the Libellus is presented under “Nonnulli Patres S. Augustino aequales” (miscellaneous fathers contemporary with St. Augustine) (Patrologia Latina/31 - Wikisource). Migne’s editorial context highlights that Leporius was a lesser-known figure of Augustine’s time whose work nonetheless merited preservation. The PL edition also reprints Galland’s prolegomena on Leporius (Full text of “Sacris Erudiri A Journal of Late Antique and Medieval Christianity”), which give historical background (e.g. noting Quesnel’s dissertation and the references in Chalcedon’s acts). Thus, readers of PL 31 receive both the text and a 18th-century scholarly commentary on it (Full text of “Sacris Erudiri A Journal of Late Antique and Medieval Christianity”). The fact that Migne situated the Libellus alongside writings of Vincent of Lérins and others from Gaul underscores the work’s value for understanding 5th-century Gaulish theology and its interaction with North African thought.

In summary, the Libellus emendationis has come down to us through careful curation by scholars from the 17th–19th centuries, and its appearance in PL 31 made it part of the standard patristic library. Modern critical scholarship has further ensured we have a reliable text to study, vindicating the authenticity and integrity of this fascinating document.

Impact and Reception in Christian Thought

The legacy of Leporius’s Libellus is notable precisely because it transformed a moment of private repentance into a public resource for the Church. In the immediate aftermath of its writing, the impact was personal and ecclesial: Leporius was welcomed back into communion. The African bishops, in their cover letter, urged the Gallic bishops to “welcome back Leporius and inform those he scandalized” of his amendment (Letters). We do not have Gallic records of their response, but given that Leporius did not return to Gaul (he remained in Africa as Augustine’s priest), it’s likely that the Libellus itself served as his testament. It quickly gained respect; contemporaries regarded Leporius not with suspicion but as a cautionary tale of conversion. St. Augustine himself apparently held Leporius in high esteem afterward – a sermon attributed to Augustine praises a priest Leporius for his piety (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia), which suggests that Augustine saw him as a trophy of grace. The Libellus, therefore, had an edifying effect: it was an example of how error can be corrected by humble submission to the truth.

As discussed, the theological content of the Libellus had broader influence on 5th-century doctrinal debates. John Cassian’s use of it in De Incarnatione (430) gave Leporius a posthumous role in the defeat of Nestorianism in the West (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW) (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). In the East, there is evidence that snippets of Leporius’s formulae were known: the acts of the Council of Chalcedon (451) quote a Western source (possibly Prosper or Cassian) that in turn drew on Leporius’s phrasing (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). Thus, indirectly, Leporius’s orthodox confession contributed to the Chalcedonian Definition. The council fathers at Chalcedon insisted, like Leporius, that “the distinction of natures” in Christ is never tantamount to a division of person (Second Council of Ephesus - Wikipedia). One historian has noted that “Leporius’s profession of faith was held in very high estimation among ancient divines”, and indeed later generations saw him as a witness to orthodoxy (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). The 6th-century African bishop Facundus cited the Libellus to defend the unity of Christ during the Three Chapters controversy (Full text of “Sacris Erudiri A Journal of Late Antique and Medieval Christianity”). Isidore of Seville (7th century) included Leporius in his catalog of heretics, but as a rare case of a heretic who repented and authored “a written satisfaction containing a confession of the Catholic faith on the Incarnation” (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). This shows that by the early Middle Ages, Leporius was remembered more for his Libellus than for his error.

In the medieval West, the text circulated enough to appear in theological florilegia. It likely influenced the way scholastic theologians understood early Christological controversies. Although not as famous as Augustine or Vincent of Lérins, Leporius occasionally surfaces in medieval commentaries as an authority who proved the correctness of Theotokos. For example, the Libellus may have informed the Carolingian theologian Ratramnus, who wrote on the two natures of Christ, or later writers who combed patristic sources for anti-Nestorian material. We also see its influence in the writings of Arnobius the Younger (5th century), who in arguing about Christ’s Incarnation echoes Leporius’s point that the divine nature remains immutable even in union with flesh (Pifarre. Pp. 261. (Scripta et Documenta, 35.) Paper n.p. - jstor) (List of editiones principes in Latin - Wikipedia). Such echoes suggest the Libellus became part of the West’s doctrinal memory.

The long-term reception of the Libellus emendationis can also be traced through its editorial history. Scholars like Pasquier Quesnel (17th c.) and Etienne Baluze examined it when editing conciliar and papal documents. In the Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique (early 20th c.), a substantial article on “Léporius” by E. Amann analyzed the Libellus and its influence (Full text of “Sacris Erudiri A Journal of Late Antique and Medieval Christianity”). Modern historians of Christology, such as Friedrich Loofs and Basil Studer, have likewise highlighted Leporius. They see his statement as an early Western attempt to articulate what later became orthodox Christology ([PDF] OUTLINES OF THE CHRISTOLOGY OF ST. AUGUSTINE). Notably, some have used Leporius’s case to explore the links between Pelagianism and Christology – i.e. how an overemphasis on human moral ability (Pelagianism) might lead one to understate Christ’s divinity (Adoptionism/Nestorianism) (2 Leporius: A Crypto-‘Pelagian’, Proto-‘Nestorian’? - Oxford Academic). In this way, Leporius’s Libellus serves as a historical case study in how theological errors can be interconnected and how the Church’s correction of one reinforces the other.

Lastly, in the spiritual sense, the Libellus emendationis had an impact as a model of repentance. Medieval hagiography sometimes pointed to figures like Leporius to assure that even teachers who erred gravely could be restored through penance. The tone of Leporius – combining firm denunciation of error with appeals for forgiveness – resonates with the Church’s penitential practices. It reminds that orthodoxy is not merely a set of abstract truths but a “rule of faith” to which even the proud must submit for the sake of salvation (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource) (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource). In later Christian thought, Leporius’s journey from superbia to supplicatio (pride to supplication) exemplifies the triumph of humility and truth. His Libellus stands as both a theological treatise and a personal testimony, and it has been received through the ages as a bit of “good out of evil” – the error of a monk turned into a confession that edified the whole Church.

Sources: The analysis above draws on the primary text of the Libellus emendationis as presented in PL 31 (Patrologia Latina/31 - Wikisource), the accompanying Epistola of the African bishops (Libellus emendationis - Wikisource), and modern scholarly evaluations (Letters) (Dissertation Spotlight - Nestorius Latinus: The Latin Reception and Critique of Nestorius of Constantinople — ANCIENT JEW REVIEW). Notably, McClintock & Strong’s Cyclopedia provides a succinct historical summary of Leporius’s life and the content of the Libellus (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia) (Leporius - Biblical Cyclopedia). The footnotes of Augustine’s Letter 219 (translated in The Works of Saint Augustine) offer insight into the dating and context (Letters). Contemporary research, such as the studies by A. Mandouze (Letters) and F. de Beer ([PDF] Tajemnica wcielenia w galijskiej literaturze V wieku na przykładzie …), further elucidate the significance of Leporius’s confession in the wider doctrinal narrative. All these sources converge in recognizing the Libellus emendationis of Leporius as a historically important and theologically rich document – one that captures a moment of doctrinal consolidation in the early Church and continues to be referenced in theological scholarship (Full text of “Sacris Erudiri A Journal of Late Antique and Medieval Christianity”) (Letters).

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube