Libellus contra Maximum Arianum (c.484)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

This 5th-century treatise by Bishop Cerealis of Castellum directly addresses Arian challenges to Nicene orthodoxy in Vandal-controlled North Africa, methodically assembling Scripture passages to affirm the full divinity of Christ and the doctrine of the Trinity without relying on philosophical arguments or ecclesiastical authority.

Historical and Ecclesiastical Context

The Libellus contra Maximum Arianum (“Little Book against Maximus the Arian”) was composed amid the later phase of the Arian controversy in North Africa. Originally sparked by Arius in the 4th century and ostensibly resolved by the Council of Nicaea (AD 325), the dispute persisted through the centuries as Arian or Homoian teachings spread among Germanic peoples. In the 5th century, the conflict took on a new urgency in North Africa under Vandal rule. The Vandals, a Germanic people who captured Carthage in AD 439, were Homoian Arians – they professed that the Son was “like the Father” but not equal in substance. They established an Arian Vandal Kingdom (435–534) in North Africa (The Kingdom of the Vandals (435–534 CE) (Illustration) - World History Encyclopedia) and often clashed with the Nicene (Catholic) majority. King Huneric (reigned 477–484) in particular intensified pressures on Nicene Christians. He convened a conference at Carthage in February 484 to debate Arian vs. Nicene positions, ostensibly to resolve the doctrinal rift (Huneric - Wikipedia). This meeting ended in disaster for the Catholics: after fruitless disputation, Huneric expelled and persecuted Nicene bishops, exiling many and even mutilating or executing some (Huneric - Wikipedia). It is in this charged ecclesiastical climate – North African Nicene bishops under Arian challenge and persecution – that Cerealis wrote his Libellus. The tract can be seen as a product of the Nicene resistance: an attempt to confound Arian theology at a time when orthodox bishops were being pressed to defend their faith on scriptural grounds alone. The role of Castellum in this context is as one of the smaller North African bishoprics caught up in the struggle. Castellum Ripense (likely in Mauretania Caesariensis, western North Africa) is recorded as Cerealis’s see (RE:Castellum 17 – Wikisource). By the late 5th century this town (Latin Castellum, “fort” or “citadel”) had passed into Vandal control, meaning Cerealis ministered under Arian dominion (2 Languages and Communities in Late Antique and Early Medieval …) (Sanctorum Hilari, Simplicii, Felicis III, romanorum pontificum, Victoris …). His Libellus was essentially a polemical response to Arianism on his home turf, reflecting both the local circumstances of Vandal persecution and the broader Nicene-Arian theological conflict.

Cerealis of Castellum: The Bishop and Opponent of Arianism

Cerealis himself was a North African Nicene bishop, about whom little is known apart from his authorship of this tract. He is identified in later sources as episcopus Castellensis – Bishop of Castellum (likely Castellum Ripense) (Vetus Latina Patristic Abbreviations) (RE:Castellum 17 – Wikisource). The Notitia (list) of African bishoprics compiled around the end of the 5th century mentions a bishop of Castellum Ripense in AD 484, almost certainly referring to Cerealis (RE:Castellum 17 – Wikisource). Thus, Cerealis was active at the time of the 484 Carthage conference and presumably was one of the many regional Catholic bishops compelled to defend orthodoxy under Vandal rule. We know that Cerealis was “an African by birth” and staunchly Nicene (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). According to the 5th-century historian Gennadius of Massilia, Cerealis’s Libellus arose directly from an encounter with an Arian prelate: “Cerealis the bishop, an African by birth, was asked by Maximus, bishop of the Arians, whether he could establish the catholic faith by a few testimonies of Divine Scripture and without any controversial assertions. This he did…not with a few testimonies as Maximus had derisively asked, but proving by copious proof-texts from both Old and New Testaments and published it in a little book” (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture) (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). This passage offers precious biographical insight: Cerealis’s reputation as a defender of Nicene orthodoxy was such that an Arian bishop (named Maximus or Maximinus in various sources) directly challenged him to prove the Catholic position using Scripture alone. The fact that he responded with a comprehensive written treatise suggests that Cerealis was learned in Scripture and willing to engage in theological controversy despite the risks. Indeed, he “did so in the name of the Lord, truth itself helping him” as Gennadius remarks (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture), implying Cerealis’s confidence that Scripture and truth were on the Nicene side. We do not have details of Cerealis’s life beyond this episode. It is likely he, like other Catholic bishops, suffered exile or punishment in the aftermath of 484 – many were banished by Huneric shortly after the Carthage disputation. He appears to have survived the persecution (Gennadius wrote his account in the late 480s or 490s, treating Cerealis’s work as recently accomplished) (DER BIBELTEXT IN DEN PSEUDO-AUGUSTINISCHEN - jstor). In any case, Cerealis’s legacy rests on his role as a North African bishop who stood up to Arian authority, crafting an erudite rebuttal to Arian theology at a critical moment in the church’s history in that region.

Overview and Structure of the Libellus

The Libellus contra Maximum Arianum (also referred to as Disputatio Cerealis contra Maximinum) is a short theological tract structured around a challenge-and-response format. It is not a verbatim transcript of a dialogue but rather a written treatise framed by an anecdotal dialogue. The text opens by setting the scene: Bishop Cerealis meets the Arian bishop “Maximinus” (called Maximus in Gennadius’s account) in Carthage, likely during the disputations around 484. Maximinus poses a test – he asks Cerealis to prove the Nicene faith (specifically, the consubstantial divinity of the Son) using only “a few scriptural testimonies” and avoiding extended argument (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). This request is described as being made “derisively” or in mockery (Latin: ut irridens Maximus quaesierat (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture)), implying the Arian bishop’s skepticism that the co-equal Trinity could be demonstrated clearly from Scripture. The structure of the work follows this setup. It likely consists of:

-

A brief prologue or dialogue section – wherein Maximinus’s challenge is stated and Cerealis resolves to answer it. According to one analysis, “in a brief opening dialogue, [Cerealis] writes, he met an Arian bishop named Maximinus” and was prompted to this exchange (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture) (Barbarian Bishops and the Churches “in barbaricis gentibus” - jstor). This section sets the tone: the Arian demands a minimalist proof, hoping to embarrass the Catholic position.

-

The main body of the Libellus – which is essentially a catena of biblical quotations and explanations marshalled by Cerealis to affirm the Nicene understanding of the Trinity (especially the Son’s divinity). True to the challenge, Cerealis largely forgoes elaborate philosophical argument or appeals to ecclesiastical authority, and instead lets Scripture speak. By all accounts, he far exceeds the “few testimonies” limit. Gennadius emphasizes that Cerealis answered “not with a few testimonies… but by copious proof texts from both Old and New Testaments”, compiled into his little book (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). The result is that the Libellus reads like a theological florilegium – a chain of biblical verses with brief comments connecting them, each chosen to refute Arian claims and uphold Catholic doctrine. The Old Testament passages he cites likely include prophecies and theophanies that imply the presence of a divine Son or Word (for example, prophecies of the Messiah as “Mighty God” in Isaiah, or Wisdom literature personifying the divine Word). The New Testament proof-texts surely feature the classic Nicene arsenal: John 1:1 (“the Word was God”), John 10:30 (“I and the Father are one”), John 14:9, Philippians 2:6, Titus 2:13, Hebrews 1:1-8, and many others that assert Christ’s divine nature, eternal pre-existence, unity with the Father, and co-equal honor. Cerealis likely also includes the Trinitarian baptismal formula (Matthew 28:19) or the Johannine testimony of the Father, Son, and Spirit to reinforce the co-equal Trinity. Each quote would be accompanied by a short elucidation to make the Nicene interpretation clear and to preclude Arian misreading. The tone is expository and affirmative – rather than attacking the Arian interlocutor with rhetoric, Cerealis methodically “establishes the catholic faith” from Scripture (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture).

-

A concluding section or epilogue – possibly rounding off the argument and turning the challenge back on the Arian. Some scholars note a tone of irony in the work: Cerealis wrote the Libellus “sicut Maximinus irridens” – “as if mocking Maximinus” (Barbarian Bishops and the Churches “in barbaricis gentibus” - jstor). In other words, by overwhelming the Arian with an abundance of biblical evidence, Cerealis effectively turns the mockery back on his challenger. The conclusion may have underscored that the Nicene position is deeply rooted in Scripture, far from the novelty that Arians alleged.

Overall, the Libellus is succinct (about 11 pages in Migne’s edition (Languages and Communities in the Late- Roman and Post)) yet densely packed with citations. It lacks the sweeping, systematic form of a treatise by a great doctor like Augustine; instead it is a concise, pointed compilation of authorities – befitting the term libellus (literally “little book”). The work’s dramatic framing (a public challenge at a conference) gave it a sense of immediacy and polemical edge. Indeed, Cerealis consciously mirrors a prior famous encounter: Saint Augustine of Hippo had, decades earlier (c. 428), debated an Arian bishop named Maximinus and later wrote a two-book rebuttal Contra Maximinum Arianum. Cerealis’s choice to identify his Arian opponent as “Maximinus” may be more than coincidence – it possibly casts Cerealis in Augustine’s footsteps, as if to say “a new Augustine rises to confound a new Maximinus” (Being Christian in Vandal Africa: The Politics of Orthodoxy in the …). Whether or not the Arian’s name was truly Maximinus, the structure of the Libellus deliberately echoes that celebrated controversy, but in miniature form. Thus the work is at once a report of a contemporary dispute and a nod to established anti-Arian tradition.

Theological Content and Refutation of Arian Doctrine

At its core, Cerealis’s Libellus is a point-by-point scriptural refutation of Arian christology. The Homoian Arians in Vandal Africa, like their 4th-century predecessors, taught that God the Father alone is true God eternal, while the Son (Christ) is a subordinate divine agent – generated before time, superior to creatures, yet not co-eternal or co-equal with the Father. They rejected the Nicene term homoousios (“of one substance”) as unscriptural and maintained that the Son was like the Father (homoios) in honor and will, but not the same in essence. Cerealis’s task was to dismantle these claims using the Arians’ own ultimate authority – Scripture. We can infer the major theological arguments he advanced:

-

The full divinity of Christ the Son: Cerealis piles up biblical testimonies that directly call the Son God or unequivocally assign Him divine attributes. For example, John 1:1–3 (“the Word was God; all things were made through Him”) would show that the Son/Word is eternal and Creator, not a creature. Verses like John 10:30 (“I and the Father are one”) and John 14:9 (“Whoever has seen me has seen the Father”) underline the Son’s unity with the Father (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). Hebrews 1:3 (“the Son is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact imprint of His being”) and 1:8 (“Your throne, O God, is forever and ever,” addressed to the Son) would be potent weapons against any diminution of Christ’s status. Cerealis likely also invokes Thomas’s confession to Jesus, “My Lord and my God!” (John 20:28) and Paul’s proclamation of Christ as “our great God and Savior” (Titus 2:13) – each a succinct apostolic witness to Christ’s deity. By presenting a cascade of such verses, Cerealis demonstrates that Scripture amply attests Christ’s true Godhead, frustrating the Arian premise that one could find only scant or ambiguous support.

-

The eternity and uncreated nature of the Son: A key Arian assertion was “there was a time when the Son was not.” Cerealis counters this by highlighting texts on Christ’s pre-existence and eternal generation. Likely he references John 1:1 again (the Word “in the beginning”), Micah 5:2 (the Messiah’s origin “from of old, from eternity”), or Proverbs 8 (understood by Nicenes as the voice of eternal Wisdom). He may also use Jesus’s own words “Before Abraham was, I AM” (John 8:58) to connect Christ with the eternal “I AM” of Exodus. The goal is to show the Son is unbounded by time, co-existent with the Father. The Nicene interpretation of Proverbs 8:22 (“The Lord begot me, the first of his ways”) might be clarified to affirm eternal generation rather than creation – perhaps Cerealis offers an explanatory note to preclude the Arian misuse of that verse. Overall, these citations insist the Son is begotten not made, the eternal Word through whom all ages were made.

-

The unity of Father and Son against Arian subordination: Cerealis likely emphasizes the inseparability and equality of Father and Son. Beyond Christ’s own claims of oneness with the Father, verses that speak of the Son possessing the fullness of deity (Colossians 2:9) or sharing the Father’s throne (Revelation 22:1, “the throne of God and of the Lamb”) would reinforce this. The Arian position relegated the Son to a secondary, intermediary role; Cerealis’s catena shows instead that the New Testament accords the Son the same divine honor and worship given to the Father (e.g. John 5:23, “that all may honor the Son just as they honor the Father”). By compiling such passages, he dismantles the Arian idea of a lesser divinity.

-

The Holy Spirit and the Trinity: Although the immediate polemical focus was the Father-Son relationship, Nicene theology also affirmed the divinity of the Holy Spirit, which Arians often downplayed. Cerealis’s Libellus may touch on the Holy Spirit’s status, though possibly more briefly. If he did, he could invoke Matthew 28:19 (baptizing “in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit”) and 1 John 5:7 (in the longer Latin text, the Comma Johanneum, which explicitly enumerates the Heavenly Witnesses – though it’s uncertain if that was in his manuscript tradition). Another likely reference is Acts 5:3-4 (lying to the Holy Spirit described as lying to God). By including the Spirit in his scriptural proofs, Cerealis would round out the Trinitarian doctrine that all three persons are co-divine. Indeed, in the same codex that preserves the Libellus, we find a separate collection “Testimonia de Deo Patre et Filio et Spiritu Sancto” – indicating the importance of a full Trinity of testimonies in this milieu (Ragyndrudis Codex - Wikipedia).

-

Implied critique of Arian hermeneutics: Though Cerealis largely avoids overt “controversial assertions” (polemical barbs) in favor of positive evidence (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture), the very selection of verses also serves to refute typical Arian proof-texts. For instance, Arians often cited John 14:28 (“the Father is greater than I”) or Colossians 1:15 (“firstborn of all creation”) to argue Christ’s inferiority. Cerealis preempts these by overwhelming them with the sensus plenior of Scripture – demonstrating that any interpretation diminishing Christ’s divinity contradicts the broader biblical revelation. In a subtle way, this approach undermines Arian exegesis: by not giving space to those counter-verses in his “few testimonies” response, Cerealis implies they are outliers misread by Arians, whereas the preponderance of Scripture supports Nicene doctrine. We do know, from Gennadius’s phrasing, that Cerealis deliberately kept “without any contentious assertion” (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture) – he did not engage in name-calling or lengthy debate on each Arian claim. The effect is that the text maintains a measured, authoritative tone, letting Scripture itself deliver the decisive rebuttal to Arianism.

In summary, the Libellus systematically argues that Jesus Christ is true God, one in being with the Father, using Scripture as the sole basis. It thereby directly challenges the Arian denial of the Trinity. The work’s sheer volume of biblical evidence is itself a rhetorical statement: whereas the Arian had sarcastically asked for just a handful of quotes (implying there were few to be found), Cerealis answered with an avalanche, “proving by copious proofs” the orthodox faith (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). This fulfilled his aim “in the name of the Lord, with Truth itself helping him” (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture) – an expression of his confidence that the truth of the consubstantial Trinity shines clearly in Scripture for those willing to see it.

Patristic References and Allusions in the Work

Interestingly, Cerealis’s approach in the Libellus is to rely almost exclusively on Scripture, with minimal direct reference to other authorities. This was intentional: the Arian challenge specifically forbade “any controversial assertions” or presumably external sources (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). In the contentious context of Vandal Africa, Homoian Arians rejected terms like homoousios and the authority of the Nicene Council or Church Fathers, insisting on “Scripture alone” arguments. Cerealis astutely met his opponents on that ground, so the Libellus does not explicitly cite the Nicene Creed, nor does it invoke Athanasius, Augustine, or other fathers by name. This sets it apart from some other anti-heretical works of the era which liberally quoted patristic precedent. For instance, in the same year 484, Eugenius of Carthage compiled a book of faith for Huneric wherein he fortified Scripture with “testimonies of the Fathers” (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). Cerealis’s tract, by contrast, sticks to the letter of the Bible. Nonetheless, patristic influence is discernible in more subtle ways:

-

Allusion to Augustine’s confrontation with Maximinus: As noted, the very scenario of Libellus contra Maximum evokes Augustine’s famous debate with an Arian bishop (also named Maximinus) decades earlier. Augustine’s subsequent treatise Contra Maximinum (written in the 420s) was much lengthier and more theologically intricate, but Cerealis’s work can be seen as a compressed, accessible counterpart. By echoing Augustine’s title and adversary, Cerealis aligns himself with the orthodox hero who had vanquished Arian arguments before. This may be a conscious nod to readers familiar with Augustine’s legacy, a way of saying the battle against Arianism continues in Africa, with Augustine’s torch being carried by a new generation (Being Christian in Vandal Africa: The Politics of Orthodoxy in the …). One modern scholar suggests that the use of the name “Maximinus” for the Arian in the Libellus was “meant to characterize Cerealis as a new Augustine” (Being Christian in Vandal Africa: The Politics of Orthodoxy in the …), positioning his little book in the tradition of Augustinian polemic.

-

Use of established “testimonia” traditions: While Cerealis doesn’t name earlier authors, he likely drew on existing compilations of anti-Arian scripture testimonies that had circulated since the 4th century. Latin fathers like St. Hilary of Poitiers and St. Ambrose had assembled many biblical proofs in their anti-Arian works, and even lists of verses (so-called testimonia) were common tools in doctrinal debates. Cerealis’s selection of verses probably reflects this heritage – for example, many of the verses he marshals are those classically employed by Athanasius or Augustine against Arians. In that sense, the Libellus is steeped in the patristic interpretive tradition even if it doesn’t overtly quote earlier writings. We might term it an “unattributed florilegium”: a bouquet of scripture that was cultivated by generations of orthodox exegesis. Notably, the Ragyndrudis Codex that preserves Cerealis’s work also contains Fides and Regula fidei texts attributed to Ambrose, Jerome, etc., and a Nicene Creed (“Regula fidei facta a Nicena”) (Ragyndrudis Codex - Wikipedia). This shows that Cerealis’s audience valued the wider patristic and conciliar context – even if the Libellus itself stays scriptural, it was read alongside those authoritative formulations.

-

Tone and language echoes: Cerealis’s writing style might unconsciously mirror that of other Latin polemicists. For instance, when presenting each verse, he likely offers a brief explanation or emphatic remark. These could echo phrases from Augustine’s or Ambrose’s works (many of which he, as a bishop, would know). For example, Augustine in Contra Maximinum often prefaces citations with “Audi quid dicat Scriptura” (“Hear what Scripture says”) or concludes “ecce, manifestum est” (“behold, it is manifest”) after demonstrating a point. Cerealis’s Libellus may contain similar turns of phrase, reflecting a shared rhetorical culture. Also, if Cerealis included any creedal statements in passing (like calling Christ “Light from Light, true God from true God”), those would be an allusion to the Nicene Creed phrasing – though he would be careful to anchor even those phrases in scriptural imagery (e.g. “Light from Light” drawn from Psalm 36:9 and John 1). We do know that Cerealis published the work “in the name of the Lord, with Truth itself helping him” (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture) – a pious invocation reminiscent of how Church Fathers often dedicate their polemics to God’s guidance. Such piety in tone shows Cerealis seeing himself within the tradition of orthodox defenders of the faith, all relying on divine truth.

In sum, the Libellus contains few explicit patristic citations due to its strategic focus on Scripture. However, it is implicitly connected to patristic thought – Augustine’s prior battle with Arianism provides a model, and the entire framework of using a chain of biblical proofs is a hallmark of Nicene apologetic method honed by earlier Fathers. Cerealis’s work is thus a bridge between the biblical text and the patristic tradition: it delivers the Fathers’ theology in a distilled biblical form, for an audience and adversary that would accept nothing else.

Impact and Historical Influence

Though Cerealis of Castellum is not a household name in church history, his Libellus contra Maximum Arianum left an appreciable mark, especially in the context of North African Christianity and early medieval transmission of anti-Arian thought. The immediate impact in his lifetime is hard to document – under Vandal censorship, Catholic writings were often suppressed. However, a few key points stand out:

-

Contemporary Recognition: The fact that Gennadius of Massilia – writing a continuation of St. Jerome’s De Viris Illustribus (On Illustrious Men) around AD 480–490 – included Cerealis and summarized his work (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture) indicates that the Libellus garnered attention beyond its local setting. Gennadius praised how effectively Cerealis answered the Arian challenge, suggesting that the tract circulated among Nicene circles, perhaps as an encouraging example of triumph in debate. This inclusion places Cerealis among the notable Christian writers of his era, meaning his work was seen as valuable in the larger Christian literary heritage of anti-heretical defense.

-

Use in Later Anti-Arian Polemics: After the Vandal kingdom fell (North Africa was reconquered by the Eastern Roman Empire in 533), Arianism largely subsided in Africa. However, in Visigothic Spain and post-Roman Gaul, Arian groups persisted into the late 6th century. Writings from earlier African Catholics were taken west by exiles and continued to be useful. There is evidence of a body of anonymous Nicene treatises against Arianism, likely composed by African bishops in exile (or under pseudonyms) – for example, the work Contra Varimadum Arianum (Against Varimadus the Arian) is a Latin handbook of biblical arguments against Homoian doctrine, written by an anonymous Catholic (possibly Vigilius of Thapsus) in the late 5th century (Against Varimadus - Wikipedia) (Vigilius Thapsensis - Henry Wace - Christian Classics Ethereal Library). Cerealis’s Libellus shares a similar style and purpose, and it’s quite possible that his approach influenced or at least paralleled these other tracts. In a scholarly comparison, Cerealis’s booklet is noted to bear “a very great similarity in form” to certain Solutiones (solutions to Arian arguments) circulating under pseudo-Augustine’s name (DER BIBELTEXT IN DEN PSEUDO-AUGUSTINISCHEN - jstor). This suggests that Cerealis’s method of compiling scripture proofs became a template that others emulated in their own anti-Arian writings. In essence, the Libellus contributed to a genre of short, scripture-based polemical works that helped finally uproot Arian teaching among the Germanic kingdoms by the 6th–7th centuries.

-

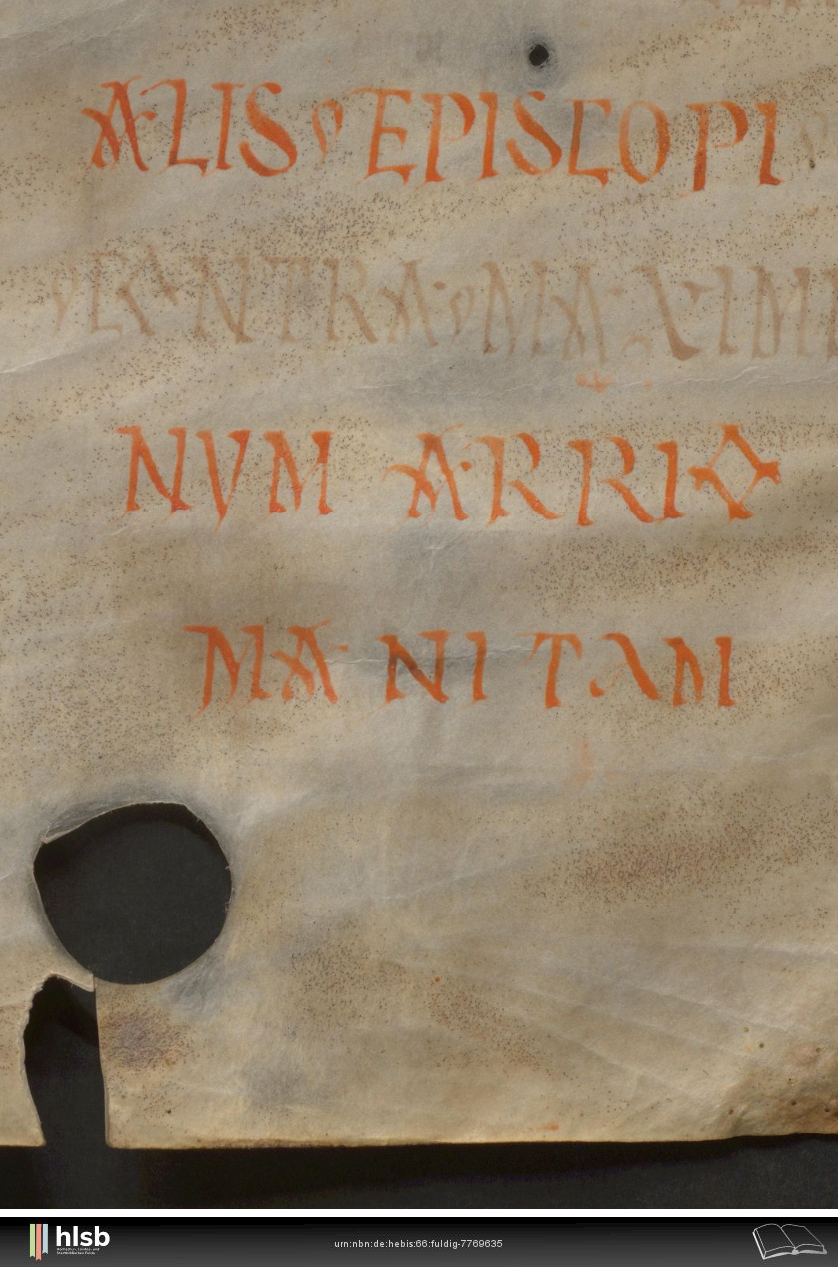

Manuscript Tradition and Early Medieval Preservation: A major testament to the Libellus’s influence is its inclusion in the famous Ragyndrudis Codex, an early 8th-century manuscript associated with Saint Boniface, the “Apostle to the Germans.”

The Ragyndrudis Codex (Codex Bonifatianus II), compiled around AD 700–730 in a Frankish monastery, contains a collection of theological and apologetical texts. Strikingly, Cerealis’s Disputatio (Libellus) is item number 3 in the codex, spanning folios 14v–34v. It appears alongside other doctrinal documents like Pope Leo’s letter, a letter of Bishop Agnellus of Ravenna on the faith, a tract by Faustus of Riez, creeds, and works of Ambrose and Isidore. The presence of Cerealis’s work in this compendium shows its valued status as an anti-heretical resource.

In Boniface’s mission territory (8th-century Germany), Arianism was no longer a living threat – most Germanic tribes had converted to Nicene Christianity by then – yet Boniface carried the codex, and tradition holds that he literally shielded himself with it when attacked by pagans in 754. The deep cuts and a visible nail-hole in the manuscript (as seen in the figure above) are revered as relics of that event.

Thus, the codex, with Cerealis’s Libellus in it, became part of Boniface’s legacy as a martyr and missionary, almost a symbol of the triumph of orthodox faith over violence and error. We may surmise that Boniface and his contemporaries included the Libellus in such a volume because it was pedagogically useful: a compact lesson in Trinitarian scriptural apologetics. It could have been read in monastic schools or used to refute lingering heterodox ideas. Its survival in this codex ensured that the work was copied and known through the Middle Ages (Patrologia Latina 58, which prints the text, relied on such manuscript transmission).

- Legacy in Orthodoxy’s narrative: Historically, the Libellus did not spawn a famous movement nor is Cerealis canonized as a prominent saint. However, his work forms part of the tapestry of anti-Arian literature that fortified the Nicene cause during a precarious time. Alongside writings by Victor of Vita, Vigilius of Thapsus, and others, Cerealis’s tract contributed to documenting the intellectual resistance of African Catholics under Arian domination. Later theologians and historians looking back on the Arian controversies have the Libellus as a window into how even relatively obscure bishops like Cerealis took up the pen in defense of orthodoxy. It underscores that the defense of the Trinity was not only the work of great luminaries like Augustine, but also of local churchmen who armed themselves with Scripture and stood firm. In that sense, the work’s impact is also inspirational: it provided a model of scriptural apologetics that is timeless. Even long after Arianism faded, Christian readers could admire Cerealis’s reliance on the Bible and his courage to respond to taunting heretics with faith and reason.

In conclusion, the Libellus contra Maximum Arianum may be “little” in size, but it encapsulates a significant chapter in church history – the perseverance of orthodox doctrine in Vandal Africa – and it influenced the arsenal of anti-heretical tools available to the early medieval Church. Cerealis’s name might have slipped into obscurity were it not for this text, yet through it his voice still speaks: a bishop armed with Scripture, confronting error and strengthening the faithful in the belief that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are one God forever.

Comparison with Augustine’s Contra Maximinum and Other Anti-Arian Tracts

It is illuminating to compare Cerealis’s Libellus with other works tackling Arianism, especially St. Augustine’s more famous treatise against an Arian bishop Maximinus and contemporaneous but lesser-known tracts:

-

Distinction from Augustine’s Contra Maximinum Arianum: Augustine’s two-book Contra Maximinum (written c. 428) is a much lengthier and more elaborate dialogue. Augustine reproduces the actual arguments of Bishop Maximinus and responds to them one by one, employing not only copious Scripture but also philosophical reasoning, theological exposition, and invocations of Church authority. Augustine engages with subtleties of Greek terms, refutes interpretations of specific verses, and advances the Nicene formula explicitly (defending the term homoousios). In contrast, Cerealis’s Libellus is briefer and more single-minded: it forgoes transcribing any Arian arguments and focuses purely on presenting the positive biblical case for the Trinity. Augustine’s tone can be adversarial and meticulous in debate, whereas Cerealis’s tone (as noted) is calmer and affirmative, sidestepping direct confrontation beyond the initial setup. We might say Augustine’s work is that of a theologian-philosopher and seasoned bishop tackling a heresiarch, whereas Cerealis’s is that of a pastor-teacher providing a handy compendium for the faithful. Another key difference is audience and circulation: Augustine’s treatise, coming from so eminent a Father, enjoyed wide copying and was cited by later councils; Cerealis’s was more local and had a modest circulation. Indeed, Augustine’s anti-Arian writings overshadowed others – they were “standard” in the West. Cerealis’s contribution, while similar in title and subject, remained comparatively obscure, only resurfacing in modern times through scholarly interest in the Patrologia Latina text. Nevertheless, the two works share a common purpose and even a common adversary (the Homoian Arian represented by “Maximinus”). Both underscore the Nicene teaching; but Augustine’s does so with authoritative weight and exhaustive argumentation, while Cerealis’s does so with efficient simplicity and Scriptural saturation. Each approach had its place: Augustine’s to intellectually dismantle Arian theology for posterity, Cerealis’s to win the scriptural high ground in a constrained debate and to edify ordinary believers.

-

Other Lesser-Known Anti-Arian Tracts: Cerealis’s Libellus is one of several relatively short works by 5th-century Latin bishops grappling with Arian or Homoian teachings outside the imperial heartlands. We have already mentioned Contra Varimadum – an anonymous handbook likely written by a North African exile (often attributed to Vigilius of Thapsus) around the same era, which compiles biblical proofs against various Arian propositions (Against Varimadus - Wikipedia) (Vigilius Thapsensis - Henry Wace - Christian Classics Ethereal Library). Like Cerealis’s work, Contra Varimadum has a structure of Q&A or chapters focusing on Christ’s divinity, using Scripture as the primary weapon. Another text from North Africa is Objectiones et Responsiones (Objections and Replies) addressed to King Thrasamund of the Vandals, traditionally ascribed to Saint Fulgentius of Ruspe. Fulgentius, writing a generation later (c. 520) to an Arian king, similarly marshals biblical and patristic arguments to answer Arian questions. In comparison to these, Cerealis’s Libellus is earlier and perhaps the simplest in format (essentially a straight list of testimonies). Vigilius’s works, for instance, sometimes masqueraded under pseudonyms (attributing themselves to earlier Fathers like Idacius Clarus or “Athanasius”) to protect the author from Vandal reprisals (Vigilius Thapsensis - Henry Wace - Christian Classics Ethereal Library). Cerealis appears to have written under his own name (or at least Gennadius names him), indicating a certain boldness or the fact that it was presented at a formal conference where authorship was known anyway. Compared to Fulgentius, who delves into more refined theological distinctions (being influenced by Augustine’s thought and writing at leisure in exile), Cerealis is more rudimentary. Yet all these tracts share a reliance on Biblical authority to confute Arian interpretations. Cerealis’s stands out for its narrative introduction of an Arian’s dare, which not all others have. This dramatization makes the Libellus quite memorable – we see an image of a lone bishop compiling his arsenal of verses “as if to mock” the overconfident heretic (Barbarian Bishops and the Churches “in barbaricis gentibus” - jstor).

-

Effectiveness and Legacy: While Augustine’s anti-Arian opus is undoubtedly more celebrated, one might argue that works like Cerealis’s Libellus were equally important on the ground level. They were digestible and easily taught, serving almost as catechetical guides on Trinitarian proof-texts. In an era when many laypeople or lower clergy might not read Augustine’s dense tomes, a short libellus could circulate and inoculate them against Arian preaching. Thus, Cerealis’s and similar tracts helped popularize the orthodox responses in a form that could be memorized or quickly referenced. By the time the Gothic and Vandal Arians were converting to Nicene Christianity (late 6th century), these compilations had done their work – providing the Nicene missionaries and apologists with ready-made “scriptural ammunition” to win doctrinal debates.

In conclusion, Augustine’s Contra Maximinum and Cerealis’s Contra Maximum are complementary rather than redundant. Augustine’s is the master-level treatise; Cerealis’s is the pocket handbook. The Libellus also fits within a continuum of North African anti-Arian efforts, distinguished by its concise focus. Its survival when many others may have been lost (we have it thanks to the medieval codex) is fortunate, as it enriches our understanding of how the orthodox faith was defended at all levels of the church – from scholarly bishops like Augustine to steadfast pastors like Cerealis. Together, they and their writings ensured that Arianism would ultimately be recognized as a failed branch of Christianity, corrected by a return to the fullness of truth as affirmed at Nicaea and proven from Scripture.

Sources: The analysis above draws on the Patrologia Latina text of Libellus contra Maximinum Arianum (PL 58:757–768) and contextual information from late antique historians. Gennadius’s De Viris Illustribus provides a synopsis of Cerealis’s work and circumstances (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture). Modern studies of Vandal Africa and Arian-Nicene debates (e.g. Victor Vitensis’s History, and scholarly summaries (Huneric - Wikipedia) (DER BIBELTEXT IN DEN PSEUDO-AUGUSTINISCHEN - jstor)) inform the historical context. The contents of the Ragyndrudis Codex, where the incipit of the Disputatio is preserved (Ragyndrudis Codex - Wikipedia), testify to the transmission and use of Cerealis’s text in the early Middle Ages. These sources collectively illuminate Cerealis’s contribution as a North African bishop upholding orthodoxy in an age of controversy and change. (Fathers of the Church - Catholic Culture) (RE:Castellum 17 – Wikisource)

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube