De Ordine Creaturarum (c.670-700)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

A 7th-century Irish synthesis of biblical cosmology and natural philosophy that shaped medieval understanding of universal order through its hierarchical organization of all creation from the Trinity to the material world, incorrectly attributed to Isidore of Seville until modern scholarship revealed its Hiberno-Latin origins.

Historical Context

Authorship and Dating: De Ordine Creaturarum is an early medieval Latin treatise on the “order of creation,” traditionally included in Patrologia Latina volume 83 under the works of Isidore of Seville. Modern scholarship, however, has shown it is pseudo-Isidorean – not actually written by Isidore (reference). Manuscript evidence and stylistic analysis indicate it was composed by an anonymous Hiberno-Latin author in 7th-century Ireland, likely in the second half of that century (reference). For centuries it circulated under famous patristic names: some medieval manuscripts even ascribed it to St. Augustine (reference) or Isidore, which is why Migne included it in Isidore’s works. Manuel C. Díaz y Díaz’s critical edition (1972) definitively established the text’s Irish provenance (reference). Thus, De Ordine Creaturarum is best understood as an Insular (Irish/Anglo-Saxon) work from around 670–700 AD, rather than a product of the earlier Visigothic Spain of Isidore. Its historical setting is the intellectually vibrant Irish monastic milieu, a generation or two after the time of Isidore and roughly contemporary with the Synod of Whitby and the rise of early English scholarship. In this context, Irish scholars were digesting the Church Fathers and classical learning, producing original syntheses – De Ordine Creaturarum among them (The Irish Background to the De XII abusiuis saeculi (Chapter 2) - Addressing Injustice in the Medieval Body Politic).

Place in Medieval Tradition: Within medieval theological and philosophical traditions, the treatise stands at the crossroads of patristic heritage and early medieval innovation. It belongs to a wave of 7th-century Irish scholarship that sought to explain biblical cosmology using both Scriptural exegesis and natural philosophy (reference). Along with works like De mirabilibus Sacrae Scripturae (a contemporaneous Irish text of 654 often attributed to “Pseudo-Augustine”) and De duodecim abusivis saeculi, it represents the apex of Hiberno-Latin learning in that era (The Irish Background to the De XII abusiuis saeculi (Chapter 2) - Addressing Injustice in the Medieval Body Politic). In fact, scholars note a close relationship between De Ordine Creaturarum and De mirabilibus: one may have drawn upon the other (The Irish Background to the De XII abusiuis saeculi (Chapter 2) - Addressing Injustice in the Medieval Body Politic). Both works reflect the Irish Church’s drive to integrate patristic theology (especially Augustinian thought) with the scientific and cosmological knowledge inherited from antiquity. By tackling questions of creation, cosmology, and eschatology in a systematic way, De Ordine Creaturarum helped transmit late antique and patristic ideas into the early medieval West. Its inclusion in monastic libraries (often under revered authors’ names) ensured it had a respected, if pseudonymous, place in the development of medieval thought.

Theological Themes

Hierarchy of Creation and Divine Order

As its title suggests, De Ordine Creaturarum is chiefly concerned with the providential ordering of all created beings. The text opens in an unexpected way – not with Genesis 1 directly, but with a consideration of the order within God Himself, the Holy Trinity. By beginning with the Trinity, the author establishes God as the perfect eternal order and the source of all order in creation.

From there, the treatise proceeds to discuss created things largely following the sequence of creation in Genesis chapter 1 (the Hexaemeron, or six days of creation). However, the author does not simply enumerate creatures in a top-down hierarchy of beings; instead, an intriguing organizational principle emerges: the work often groups topics according to the hierarchy of the four classical elements – fire, air, water, earth – from most subtle to most material.

In other words, the narrative of creation is structured in part by the idea that all creatures are composed of these elements in varying degrees. Fire is discussed first (associated with the highest or heavenly part of creation), then air, then water, then earth, reflecting a worldview inherited from ancient natural philosophy. This framework is woven into the biblical chronology: for example, the creation of celestial light or angels might be linked with the element of fire (light and heat), the firmament with air, the separation of waters with the water element, and the formation of land and life with earth.

The overarching theme is that God imposed a rational order on the universe, with each creature and element occupying its proper place in a grand hierarchy of being. This concept of a divinely ordained cosmos (Greek for order) aligns with the classical “Great Chain of Being” idea, albeit articulated in a Christian register. The author repeatedly stresses that nothing in creation is random; everything from angels to earthly creatures is arranged according to measure, number, and weight under God’s design – a profoundly Augustinian notion of order and harmony in creation.

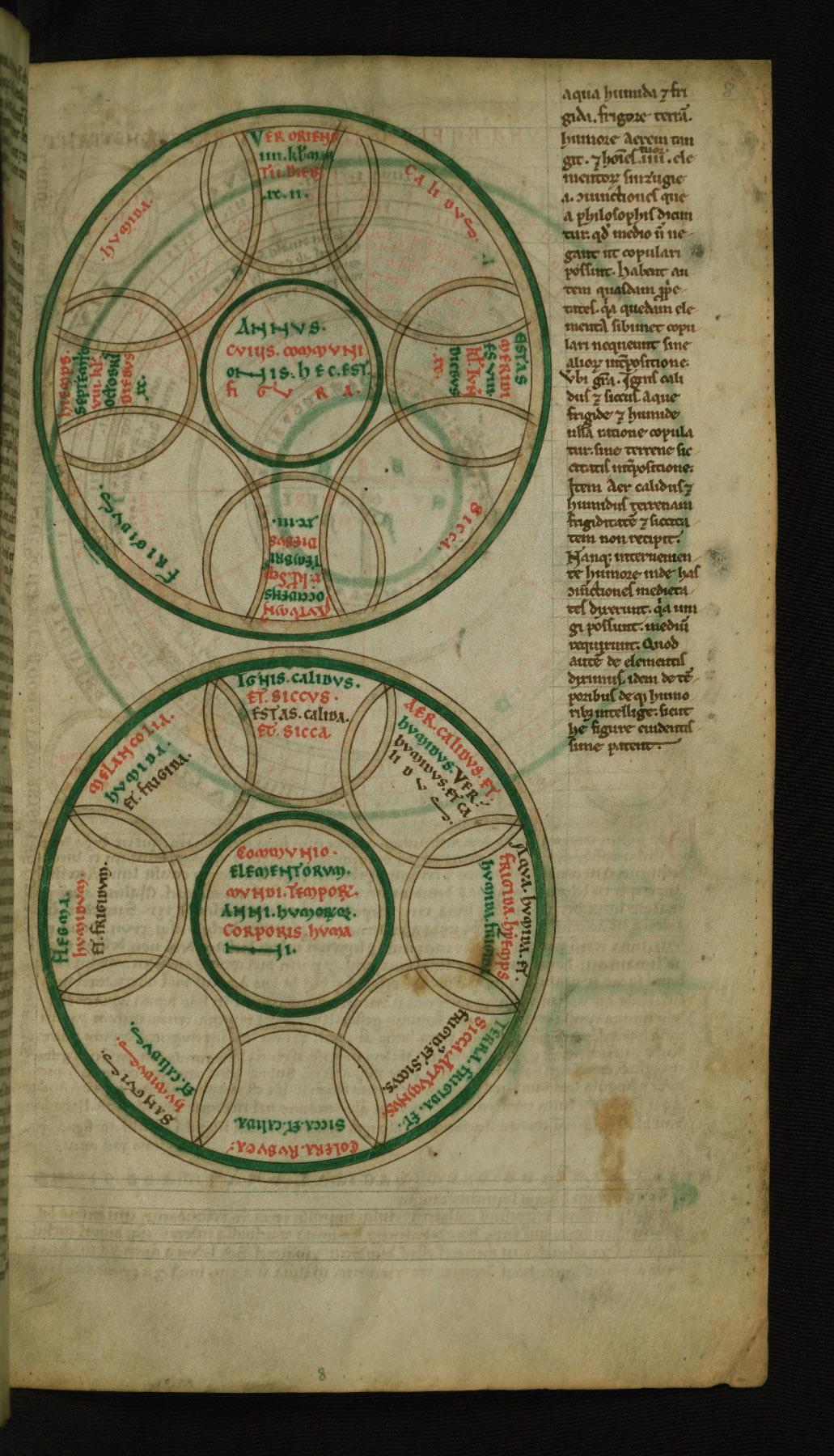

Medieval thinkers often visualized the cosmos as a harmonious hierarchy. In this 12th-century diagram (inspired by works of Bede and Isidore), overlapping wheels link the elements, seasons, and humors, symbolizing the microcosm–macrocosm relationship. The cross-shaped alignment of the circles signifies Christ restoring cosmic order after the Fall. Such imagery echoes the themes of De Ordine Creaturarum, which presents creation as a unified, ordered whole under divine governance.

Diagram of the microcosmic-macrocosmic harmony from Walters Ms. W.73, Cosmography (late 12th century)

Angelic and Cosmic Hierarchy

De Ordine Creaturarum includes both the visible and invisible creation in its scope, situating angels and heavenly beings within the ordered universe. The text likely addresses the creation of angels (a common topic in Hexaemeron literature, since Genesis 1 does not explicitly mention when angels were created). The author’s approach is deeply influenced by Augustinian thought and possibly Neoplatonic hierarchy: he portrays a gradation from the spiritual down to the material.

Notably, after discussing the initial perfection of creation, the treatise turns to the disruption of order by sin and the subsequent divine reordering. It describes how certain angels fell from their original state (Lucifer and his cohort), and later how humanity fell, thus necessitating a “reordering” or restoration by God. In this way, the work moves from the Hexaemeron (the six-day creation narrative) to what we might call a post-creational history of the universe, including the Fall of angels, the Fall of man, and finally eschatology.

Toward its conclusion, De Ordine Creaturarum takes on an eschatological tone: it discusses the final destiny of creation, the purification and renewal required to restore the original divine order. For instance, it references the “purgatorial fires” – an early mention of a purifying fire for souls – tying the fate of individual souls to the cosmological order. The inclusion of a purgatorial concept shows the author engaging with developing Christian theology about the afterlife and the ultimate restoration of harmony.

Theologically, this reflects an Augustinian framework: all creation began in ordered harmony, was disturbed by sin, and will be restored to order by Christ’s redemptive work. Indeed, the author implicitly invokes Christ as the one who re-establishes the broken order – a theme illustrated in the diagrams above and echoed in the text’s closing sections.

Connections to Neoplatonism and Augustinian Ideas: Throughout these discussions, one senses a blend of biblical doctrine with philosophical concepts inherited from Neoplatonism (likely filtered through St. Augustine and others). The very idea of descending levels of creation from the One (God) and the ultimate return of creation to God has a Neoplatonic character, adapted to Christian theology. For example, the text’s structure – from the Trinity (the ultimate One), down through the material elements, and back to the final consummation – resembles the exitus-reditus (exit and return) model found in Augustinian and Pseudo-Dionysian thought. The treatise’s concern with invisible realities (angels, heavens) and intelligible order shows kinship with Pseudo-Dionysius’s celestial hierarchy, although De Ordine Creaturarum does not explicitly enumerate the nine choirs of angels as Dionysius does. Instead, its hierarchy is broader, encompassing all creation. The influence of St. Augustine is palpable. Augustine taught that God created all things with form and order, and that even the seemingly lowliest creature has its place in the divine plan – these ideas surface repeatedly. Moreover, the author’s decision to start with the Trinity parallels Augustine’s method of moving from God to creation, and the emphasis on the ordinalitas (ordered relationship) among creatures is very much in line with Augustinian metaphysics. There are also hints of Augustinian (and semi-Augustinian) theology in the text’s treatment of grace and free will. Interestingly, later readers like Bede detected what they called “suspiciously semi-Pelagian” ideas in this work (reference). This likely refers to the author’s stance on the role of human effort in returning to God’s order – perhaps the text is overly optimistic about free will or the ability of the fallen creature to seek God, in a way that a strict Augustinian might find uncomfortably close to the Pelagian heresy. Such nuances show the text engaging with the theological debates of late antiquity (Pelagianism, grace, and nature) within its cosmological narrative. Overall, De Ordine Creaturarum presents a theological cosmology: a vision of a universe where everything, from angels to elements, fits into a God-given order, and where even after disruption by sin, the divine plan moves toward restoration. The universe is portrayed as a hierarchy of creation ordered by God’s wisdom – a theme deeply resonant with both Neoplatonic cosmic hierarchy and the Christian idea of a providential design.

Hexaemeral Commentary: In developing these themes, the treatise functions partly as a Hexaemeron commentary. It systematically walks through the days of creation in Genesis, offering interpretations and expansions on each step. For example, when discussing Day 2 (the firmament dividing waters), the author delves into the nature of the “waters above the heavens,” a classic question in patristic cosmology (reference). He likely cites earlier Church Fathers’ opinions (perhaps Augustine, who suggested the “waters above” might have a spiritual meaning, and others like Basil or Ambrose who took them more literally). The order of creation is thus examined both literally and allegorically. De Ordine Creaturarum tends toward a literal, orderly reading of Genesis – it does not radically allegorize the creation days, but rather tries to explain them in rational terms. In doing so, it incorporates concepts from natural science (for instance, explaining the phases of the moon or the mechanism of the tides in the context of Day 4 or Day 5 of creation) (reference). This integration of natural philosophy into biblical commentary was innovative. It shows the author’s intent to present the cosmos as both a theological and a physical reality – God’s handiwork that can be understood through reason and observation as well as through Scripture. For instance, the question of whether the Earth is round or flat is openly addressed (reference). The author likely affirms the Earth’s sphericity (a view shared by learned late antique authors and by Bede later on) while reconciling it with biblical language. By tackling such issues, the treatise reassures its readers that the Bible’s account of creation is compatible with the observed structure of the world – a key concern in the early Middle Ages as classical knowledge re-emerged in Christian contexts. In sum, the theological themes of De Ordine Creaturarum encompass the full sweep of creation: from God’s triune nature, through the establishment of an ordered universe, the ranking of elements and creatures, the interplay of spiritual and material realms, the disruption of that order by sin, and finally the hope of cosmic restoration. It stands as a “majestic summation of all creation – visible and invisible – as the domain of Christ,” in the words of one modern commentator, uniting cosmology with salvation history.

Influence on Later Thought

Reception and Manuscript Transmission: Despite its pseudonymous origin, De Ordine Creaturarum exerted significant influence on medieval scholars – particularly in the early medieval Insular world and beyond. Its popularity is evidenced by over twenty surviving manuscripts, ranging from England to continental Europe (even as far as Prague) (reference). Irish and Anglo-Saxon missionaries carried this text to Europe, embedding its ideas in monastic libraries abroad. Because it was often attributed to authoritative figures (Isidore or Augustine), medieval readers treated its content with respect. For example, one 14th-century copy from Durham Cathedral Library lists the work as if it were by Augustine, and another medieval catalog notes it among Isidore’s writings (reference) (reference). These attributions likely helped the work’s ideas spread under the guise of patristic wisdom. In some high-medieval manuscripts, scribes even took care to obscure or “encrypt” a few lines of the text that they deemed theologically problematic (specifically in chapter 12), rather than discard the whole work (reference) (reference). This indicates that De Ordine Creaturarum was valuable enough to preserve, with minor doctrinal tweaks, well into the later Middle Ages. By the 12th century, the treatise’s ideas were being included (sometimes via intermediaries) in encyclopedic compilations and scientific handbooks for monks. For instance, the late-12th-century Cosmography manuscript (Walters MS W.73) drawn from Isidore and Bede – both of whom were influenced by De Ordine Creaturarum – presents diagrams on winds, elements, and tides that echo this work’s content (Cosmography Manuscript (12th Century) — The Public Domain Review). Thus, even when not named, De Ordine Creaturarum’s vision of a structured, harmonious cosmos permeated medieval learning.

Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Tradition: The most notable direct influence is on the Venerable Bede (673–735), the great Anglo-Saxon monk and scholar. Bede clearly knew De Ordine Creaturarum and used it as a source for his own treatise De Natura Rerum (c. 703) (reference). De Natura Rerum was Bede’s compendium of natural science and cosmology; in composing it he drew heavily on Isidore of Seville’s works but also on this anonymous Irish treatise. Bede seems to have borrowed factual content (e.g. explanations of the ocean’s tides, lunar phases, and possibly cosmological structure) from De Ordine Creaturarum, while omitting or modifying theological points he found suspect (reference). As noted, Bede avoided the “semi-Pelagian” aspects – likely toning down any statements that overemphasized human free will or the idea that creation’s perfection could be restored by anything other than divine grace (reference). The fact that Bede – himself a careful and orthodox theologian – trusted large portions of this work enough to incorporate them is a strong testament to its influence. Through Bede’s immensely popular writings, the ideas of De Ordine Creaturarum reached a much wider audience. For example, Bede’s De Natura Rerum and his biblical commentaries became standard texts in Carolingian and later medieval schools, carrying forward insights originally from the Irish author. In this way, De Ordine Creaturarum had an indirect yet decisive impact on the development of early medieval science and cosmology.

Impact on Scholars and Theologians: Beyond Bede, other early medieval figures show awareness of the work’s themes. Aldhelm of Wessex (d. 709), an exact contemporary of the treatise’s composition, was immersed in Hiberno-Latin learning; while we have no explicit citation by Aldhelm, the ornate style and encyclopedic curiosity of De Ordine Creaturarum find resonance in Aldhelm’s own writings. Later, in the Carolingian renaissance (9th century), scholars like Rabanus Maurus and Johannes Scotus Eriugena encountered the text’s ideas. Rabanus, compiling his encyclopedic De Universo, drew on Isidore extensively and likely absorbed material that originated in De Ordine Creaturarum (especially if he consulted manuscripts attributing it to Isidore). John Scotus Eriugena (c. 9th century), who created a grand synthesis of cosmology and theology in his Periphyseon, was not the first to attempt a rational systematization of creation – De Ordine Creaturarum had pioneered that approach a century or two earlier (37 - Creating Knowledge and Knowing Creation in Theological and …). Indeed, Eriugena’s biographers note that the anonymous Irish author of De Ordine Creaturarum “built on [patristic foundations], advising that first the reader should examine what was best…”, prefiguring Eriugena’s own method (37 - Creating Knowledge and Knowing Creation in Theological and …). In short, later medieval thinkers recognized that this 7th-century treatise was a forerunner of systematic cosmological thought in the Latin West.

Citations and Adaptations: In terms of direct citation, De Ordine Creaturarum is occasionally quoted or paraphrased (often under another name). For example, a High Medieval author might quote “Isidore” on a point about the four elements or the structure of heaven and unknowingly be echoing this text. By the 12th–13th centuries, university Scholastics had access to a fuller range of authorities (including Aristotle and Pseudo-Dionysius), so the explicit use of De Ordine Creaturarum waned. Yet its legacy persisted in the general assumptions and teachings about the ordered universe that it helped establish. Even in the Scholastic Summae, one can find concepts that harken back to this treatise – such as the idea that creation is a hierarchy directed toward God as final end (Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae opens with the “order of creation to God” in its very structure ([PDF] The Aquinas Review), an idea commonplace by then). In summary, De Ordine Creaturarum’s influence on later thought is seen not so much in frequent name-dropping of the text, but in the transmission of its content and cosmological vision through more famous channels. It was a conduit for patristic and classical knowledge into the medieval curriculum: a hidden cornerstone that undergirded the medieval understanding of the cosmos as a divinely ordered, hierarchical, and comprehensible whole.

Comparative Analysis

De Ordine Creaturarum can be illuminatingly compared with other patristic and medieval works that address the structure of creation and the hierarchy of the universe. Such comparison highlights both the uniqueness of this treatise and its continuity with tradition:

-

Patristic Hexaemeron Literature: The work stands in the line of earlier Hexaemeron commentaries by Church Fathers like St. Basil the Great and St. Ambrose. Basil’s Greek Hexaemeron (4th century) and Ambrose’s Latin Hexameron (late 4th century) are homiletic commentaries on the six days of creation. Like De Ordine Creaturarum, they expound Genesis 1 in detail, praising the order and goodness of creation. However, Basil and Ambrose largely restrict themselves to the biblical narrative and moral exhortation, whereas De Ordine Creaturarum ventures further into encyclopedic and philosophical territory (e.g. discussing earth’s shape or natural phenomena in a “scientific” manner (reference)). Moreover, Ambrose’s work doesn’t go beyond the sixth day, while De Ordine Creaturarum extends its scope to include angelology and eschatology (topics more akin to Augustine). In comparison to these patristic sources, the Irish author had the benefit of additional two centuries of intellectual development and sources. He could draw not only on Basil/Ambrose, but also on Augustine’s reflections and a growing body of Latin encyclopedic writing. Thus, De Ordine Creaturarum reads as a synthesis – less literary than Basil or Ambrose, but more comprehensive in scope. It shares with the patristic Hexaemera a reverence for the hierarchical arrangement of creation (e.g. light before animals, etc., showing God’s design), and often echoes their theological points (such as the idea that creation reflects God’s glory and wisdom). Yet it also differs by systematically incorporating what the author calls “mundana philosophia” (worldly philosophy) (reference). In doing so, it bridges patristic commentary with a quasi-encyclopedic approach foreshadowing medieval scholastic compilations.

-

Augustinian Cosmos and Neoplatonic Structure: St. Augustine offered profound analyses of creation in works like Confessions (Book XII-XIII) and De Genesi ad Litteram. Augustine introduced ideas like the simultaneous creation of all things in seed forms (rationes seminales) and a strong emphasis on the allegorical meaning of Genesis. By contrast, De Ordine Creaturarum adheres more to a sequential, literal account of creation (closer to Basil/Ambrose) – it follows the day-by-day progression (reference) rather than positing an instantaneous creation of matter as Augustine did. However, the influence of Augustine’s worldview is still present. For example, Augustine’s concept of the ordo creaturarum (order of creatures) and the idea that God established a hierarchy from angels down to worms for the beauty of the whole are clearly reflected in the Irish treatise. Moreover, the psychological and moral dimensions Augustine saw in creation’s order (e.g. the higher and lower parts of creation paralleling spirit and flesh) can be discerned in how De Ordine Creaturarum discusses the fall of angels and humans. There is also an implicit Neoplatonic tone (likely mediated by Augustine and Boethius): the gradation of being from God to nothingness, the dependency of all creation on the One, and the eventual return (reditus) of creation to God’s intended order – themes common to both this treatise and Augustinian-Platonic thought (reference). In comparison to Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite’s famous De Coelesti Hierarchia (5th–6th century), which rigorously categorizes the nine orders of angels, De Ordine Creaturarum is less narrowly focused on angels and more on the total structure of reality. Pseudo-Dionysius’ influence in the Latin West blossomed later (after 9th century), but interestingly our Irish author already speaks of hierarchical order in creation in a way that anticipates the scholastic fascination with hierarchy. Both works share the notion that the universe is a series of intermediating levels between God and matter, but De Ordine Creaturarum populates that series not just with angelic choirs, but with the elements, the celestial spheres, humanity, etc., giving a more holistic cosmology.

-

Isidore of Seville and Encyclopedic Tradition: Given that De Ordine Creaturarum was once attributed to Isidore, it’s worth comparing it to Isidore’s genuine work De Natura Rerum (613 AD). Isidore’s De Natura Rerum is a brief textbook on cosmology and natural phenomena for a Visigothic king, summarizing classical knowledge (astronomy, geography, meteorology) in a Christian framework. De Ordine Creaturarum certainly draws on a similar knowledge base – indeed, it covers many of the same “natura rerum” topics like astronomical cycles, elements, and physical explanations (reference). But it differs in purpose and tone: Isidore’s work is largely descriptive and didactic, whereas De Ordine Creaturarum is more speculative and theological. The Irish author uses natural facts to support a larger theological narrative about creation’s order under God. We might say De Ordine Creaturarum marries Isidore’s encyclopedic approach with Augustine’s contemplative theology. By the time of Bede’s De Natura Rerum (which postdates De Ordine by a few decades), we see a similar fusion – Bede’s work is basically Isidorean in content but, influenced by the Irish treatise, it occasionally infuses spiritual significance into the cosmology. The Irish tradition behind De Ordine Creaturarum can also be compared to works like De mirabilibus Sacrae Scripturae (mentioned earlier) and the Irish “computistical” literature. Irish scholars were leaders in computus (the science of time and calendar) and often integrated cosmological diagrams and explanations. The treatise under study shares this integrative spirit – it isn’t just theology in abstraction, but grounded in the physical observations of time, tides, stars, etc.

-

Scholastic and Later Medieval Works: When we move to the High Middle Ages, works like Peter Lombard’s Sentences (12th c.) and Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae (13th c.) devote substantial sections to creation, angels, and the order of the universe. By then, a more systematic scholastic method is in play, but many foundational ideas remain the same. For example, Aquinas in Summa Part I asks questions about the creation of angels, the formation of the world, the hierarchy of creatures, and the governance of creation – all themes that De Ordine Creaturarum had addressed in a less formal way. Aquinas cites authorities like Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius, and occasionally Isidore; if he had a copy of De Ordine Creaturarum, he likely would have assumed it was Isidore or Augustine and might indirectly reflect it. One key difference is that scholastic authors had Aristotle’s philosophy at hand. De Ordine Creaturarum, being much earlier, works with a pre-Aristotelian (or partially Aristotelian via second-hand) natural philosophy – the four elements, the spherical cosmos, etc., derived from authors like Plato’s Timaeus tradition or Roman encyclopedists. By Aquinas’s time, the understanding of physics and cosmology had advanced with Aristotelian clarity, but the metaphysical and theological convictions were consistent: both the 7th-century monk and the 13th-century friar believed in a structured universe where every creature from seraph to snail has a place in the divine hierarchy. In that sense, De Ordine Creaturarum prefigures later scholastic discussions. It is also interesting to compare it with the 12th-century School of Chartres philosophers (like Thierry of Chartres), who wrote their own Hexaemeron commentaries blending Plato’s cosmology with Genesis. They, too, posited the four elements and a macrocosm-microcosm parallel under God’s design, much as our Irish author did long before. This shows a continuity of interest: medieval thinkers repeatedly returned to Genesis and cosmology, often independently “rediscovering” approaches that De Ordine Creaturarum had earlier exemplified.

In summary, De Ordine Creaturarum shares with patristic works a fidelity to the biblical creation account and an emphasis on a divinely ordained hierarchy. It goes beyond its patristic predecessors by incorporating a broader range of topics (science and eschatology), a trait it passes on to medieval encyclopedists. Compared to high scholastic texts, it is less rigorously analytical but contains in nuce many of the same issues later scholars would systematize. It occupies a bridge position – looking back to the Fathers (Augustine, Basil, etc.) for authority (reference), while foreshadowing the comprehensive intellectual frameworks of the high Middle Ages. As one scholar put it, the treatise is “a work of magnificent conception” (The Irish Background to the De XII abusiuis saeculi (Chapter 2) - Addressing Injustice in the Medieval Body Politic) for its time, attempting what later only large summae would: to chart the whole order of creation, from alpha to omega, in one cohesive vision.

Philosophical Implications

Beyond its overt theological content, De Ordine Creaturarum carries significant metaphysical and epistemological implications characteristic of medieval Christian philosophy.

Metaphysical Worldview: The treatise assumes a profoundly ordered and hierarchical metaphysics. Reality is not a chaotic assemblage but an integrated cosmos – a structured whole in which every level of being has its place. This reflects the classical idea of a cosmos governed by order (logos), now firmly grounded in Christian doctrine of creation. Metaphysically, the text posits a chain of being that stretches from God down to inanimate matter. God, as the Holy Trinity, is the supreme ordering principle – the source of all existence and harmony (reference). Immediately below God are the highest created intelligences (the angels), then the celestial realm (stars, planets, elements in their pure form), then humans (a microcosm of both spirit and matter), then animals, plants, and minerals. This gradation of being is not explicitly diagrammed by the author, but it underlies the entire discussion. For example, when he notes that fire is the subtlest element and earth the lowest (reference), he’s aligning with a worldview where even the material constituents of things are ranked. The hierarchy of the four elements – fire > air > water > earth – used in the text is a direct inheritance from ancient Greek philosophy (Empedocles/Aristotle), showing that the medieval author assumed those elemental distinctions to be objectively true about reality. By structuring his treatise around that hierarchy, he signals a belief that the physical composition of the universe itself has an ordered architecture (reference). All creatures are a combination of those elements, so the position of a creature in the hierarchy of being can be discussed in terms of its elemental makeup (e.g. stars are mostly fire and air, fish are mostly water, etc.), an almost proto-scientific metaphysics. Moreover, the author’s treatment of the human being likely reflects the traditional microcosm concept – that man is a “little world” containing all elements and reflecting the larger creation. This is evidenced by parallel discussions of the four bodily humors and four seasons corresponding to the elements in later diagrams ( ‘Above: Diagram of a cube; Below: Diagram of the microcosmic-macrocosmic harmony.’ from Walters Ms. W.73, Cosmography (late 12th century) - Public Domain Image Archive ), and while our treatise itself may not detail humors, it implicitly uses the same framework of correspondences common in early medieval thought.

Crucially, the text’s metaphysics is teleological and theocentric: everything in creation has a purpose oriented toward God. Nothing exists in isolation; rather, each creature’s being and goodness consist in its ordained place and role. This is a deeply Augustinian idea – Augustine taught that the perfection of the universe lies in the balanced interrelation of all its parts under God’s plan, even if some parts seem “lesser” or even evil in isolation. De Ordine Creaturarum echoes this: for instance, the fall of some angels and humans, while a disruption, is not the end of the story; it becomes part of a larger divine providence that will set things right (an outlook akin to Augustine’s felix culpa reasoning). The mention of purgatorial fire ties into medieval metaphysics by suggesting that even after death, souls undergo a physical purging process – a blending of spiritual and material realms that is quite metaphysical in nature (reference). The idea that an element (fire) can cleanse a spiritual entity (the soul) implies an underlying unity of reality: material elements can affect spiritual beings by God’s arrangement. This reveals the sacramental ontology of the medieval mind, where physical things are instruments of divine action on spiritual realities.

Epistemology and Method: Epistemologically, De Ordine Creaturarum showcases the medieval approach to knowledge, which relies on a harmony of authority and reason. The author explicitly positions his work as following the “footsteps of Scripture” and the interpretations of the maiores (the Fathers, the “greater ones” who have explained these things before) (reference). This deference indicates the epistemic principle that truth is to be sought by looking back to authoritative wisdom. He is careful to claim that nothing in his account deviates from the consensus of “good and catholic teachers” (reference), underscoring that orthodoxy is a governing criterion for truth in his epistemology. At the same time, the treatise employs what it calls “mundana philosophia” – knowledge of the natural world drawn from human reason and observation (reference). The inclusion of explanations for empirical phenomena (like why the oceans have tides or how the moon’s phases work) shows that the author values rational inquiry and empirical knowledge as complementary to revealed knowledge. This reflects the early medieval conviction that faith and reason are compatible avenues to truth. The world, being rationally designed by God, can be understood by human reason, and such understanding ultimately glorifies the Creator. Therefore, studying nature (philosophia) is not opposed to studying Scripture; rather, in this work, natural philosophy is put in service of exegesis. For example, when interpreting the creation of the moon and sun, the author might include a mini-lesson on astronomy so that the reader grasps the order and regularity God built into the heavens (reference). This use of reason to illuminate Scripture prefigures the Scholastic method (where theology engages Aristotelian science).

It’s also noteworthy that the author discusses questions that imply a critical examination of various viewpoints – such as whether the earth is round or flat (reference). This suggests a dialectical epistemology: he knows there are differing opinions (some Church Fathers like Lactantius argued for a flat earth, while others and classical scientists held it round), and he finds a resolution that fits both reason and faith. While we don’t have his exact argument quoted, the mere inclusion of the question shows a confidence that apparent conflicts between “secular” knowledge and biblical cosmology can be reconciled through careful reasoning. We see here the seeds of the later medieval quaestio method, where a question is posed, arguments pro and con are weighed, and a synthesis is achieved. In De Ordine Creaturarum, this is done in a simpler, narrative form, but the intellectual move is similar.

Great Chain of Being and Scala Naturae: In philosophical terms, the treatise endorses what later became known as the Great Chain of Being (scala naturae) concept – that all beings form a continuous chain from the lowest to the highest. The text doesn’t use that exact term, but by meticulously enumerating every level of creation and emphasizing none is superfluous, it tacitly affirms that philosophical principle. Medieval Christian philosophy took from Neoplatonism the idea that the abundance of creation is itself a reflection of God’s goodness – a principle clearly at work in the Irish author’s mind as he finds theological significance in everything from fiery heavens to earthly dirt. Implicit is the principle of plenitude (that God created a full range of beings, filling the gap between extremes) and the principle of continuity (adjacent ranks of being differ by the least possible degree). For instance, humans are mid-way between angels and animals, sharing sense-perception with animals and reason with angels – a classic continuity argument that De Ordine Creaturarum would have known from patristic sources and seemingly embraces. The microcosm-macrocosm analogy – man as a miniature of the world – is another philosophical idea present in the treatise’s milieu ( ‘Above: Diagram of a cube; Below: Diagram of the microcosmic-macrocosmic harmony.’ from Walters Ms. W.73, Cosmography (late 12th century) - Public Domain Image Archive ). This analogy implies an epistemological optimism: by understanding ourselves (microcosm), we can understand something about the whole creation (macrocosm), and vice versa, because the same divine logic underpins both. Such an assumption justifies the treatise’s broad scope; the author can freely move from discussing the soul to discussing the stars, knowing that all knowledge interconnects.

Integration of Natural and Supernatural: Another implication is how De Ordine Creaturarum handles the division (or lack thereof) between natural and supernatural. In modern thought, we distinguish physics from metaphysics sharply; in this 7th-century work, the two flow together. The super-celestial waters mentioned (reference), for example, raise a metaphysical issue: are these literally water (a natural element) existing beyond the stars, or a metaphor for spiritual realities? The author likely entertains a literal existence (many early medieval scholars did), which means his cosmology extends the physical world into realms we might consider supernatural (above the heavens). Similarly, discussing purgatorial fire means physical fire has a role in the spiritual realm of purgatory. This seamless blending is a hallmark of medieval philosophy, which doesn’t compartmentalize the universe. The visible and invisible are two parts of one continuum. In philosophical terms, De Ordine Creaturarum presents a kind of Christian neo-Platonic cosmology where the distinction between matter and spirit is one of degree and function, not absolute separation. All is under the governance of divine Providentia (Providence), a concept the author surely inherited from figures like Boethius and Gregory the Great.

Finally, the text’s concluding assertion (addressed to the reader) that everything said is in agreement with “catholic experts” (reference) reveals a medieval epistemological modesty: knowledge is a communal, cumulative enterprise, not the innovation of one mind. The author subsumes his voice under the chorus of tradition. This speaks to the medieval conception of authority – truth is verified by its consonance with the inherited wisdom of the Church. Even as the work pushes into new explanatory territory, it frames itself as nothing novel, only the unfolding of what was always implicitly true in Scripture and patristic teaching. This humble, authority-bound approach is itself a philosophical stance on how truth is known (through respect for auctoritas).

In conclusion, De Ordine Creaturarum embodies the medieval Christian philosophical vision: a metaphysically ordered universe radiating from the One (God), an epistemology that unites faith and reason, and a view of knowledge as the harmonious synthesis of classical philosophy with biblical revelation. Its assumptions laid groundwork for the great philosophical syntheses to come, making it a quiet but pivotal chapter in the history of ideas.

Linguistic and Stylistic Features

The Latin style of De Ordine Creaturarum reflects its origin in a learned 7th-century monastic context, showing both the influence of classical Latin and the peculiarities of Hiberno-Latin literary culture. Several features stand out:

Latin Prose Style: The prose is generally expository and didactic, aiming to explain and instruct. It is not a simple Latin; at times the author adopts a high register with elaborate periodic sentences and rich vocabulary. Scholars have noted instances of almost bombastic rhetoric in the text – for example, the opening of chapter 14 reportedly launches into a particularly florid passage (Aldhelm’s prose style and its origins - Anglo-Saxon England). This “sporadic bombast” likely involves strings of adjectives, parallel constructions, and perhaps alliteration or rhyme, all of which were beloved devices in Insular Latin writing. Such flourishes were a mark of erudition and were used to elevate the discourse, especially when speaking about the majesty of creation or the glory of God. Yet, these high-flying sections are interspersed with straightforward explanatory prose when addressing technical points. The author thus modulates his style: lofty and eloquent when contemplating higher mysteries, plain and methodical when teaching natural facts. This dual register matches the content – sublime theological insights couched in almost homiletic language, alternating with almost textbook-like clarity for scientific descriptions.

Hiberno-Latin Traits: Being a product of the Irish scholarly milieu, the work exhibits typical Hiberno-Latin idiosyncrasies. The Irish monks of this period were known to employ uncommon vocabulary (sometimes reviving obscure Latin words or coining neologisms) and to insert Irish favorite devices like extensive use of synonyms or periphrasis for variation. For instance, the text might use multiple Latin terms for “creation” or “order” to display learning and avoid repetition. Irish Latin authors also had a penchant for figurae etymologicae (using words of the same root together) and alliteration (e.g., fragor et fervor – just as an illustrative guess). Without a direct quotation it’s hard to enumerate exactly, but one can surmise that De Ordine Creaturarum contains echoes of the style found in writings like those of Virgil of Salzburg or the Irish Hisperica Famina (though certainly more restrained than the latter). We do know the text is written in prose divided into chapters or sections (modern editors count 15 sections) and totals about 1245 lines of Latin (reference), indicating it’s relatively concise. The sentences probably range from medium to long, with multiple subordinate clauses – a style influenced by the Latin Vulgate Bible and by late antique authors like Augustine and Gregory. Irish scribes were deeply familiar with the Vulgate, so biblical Latinisms appear in the work. For example, the author might use fiat lux (“let there be light”) not just as a quote but as a stylistic model, or employ Latin biblical turns of phrase like “et factum est” (“and it was done”) to give his prose a scriptural rhythm.

Rhetorical Strategies: Rhetorically, the treatise employs several classical techniques adapted to Christian discourse. In the preface (or early lines), the author uses a humility topos: he insists on following the “vestigia” (footsteps) of Scripture and earlier authorities (reference), positioning himself as a faithful transmitter rather than an innovator. This is a deliberate ethos appeal, reassuring the reader of the writer’s orthodox intent. As the argument progresses, the author likely poses rhetorical questions or objections, a method common in didactic texts to pre-empt doubts. For example, when discussing the waters above the heavens or the earth’s shape, he might introduce “One might ask, how can there be waters above the firmament?” and then answer it. This question-and-answer style, reminiscent of catechetical works, helps structure the information logically. There are also instances of apostrophe – direct address to the reader – especially in concluding remarks where he urges the reader to accept what has been said as aligning with the faith. The ending of the treatise famously proclaims that everything written is “in full agreement with good and catholic readers (or experts)” (reference). This closing statement functions as a peroration, reinforcing the orthodoxy and seeking the audience’s assent. It’s effectively saying: “All I have said conforms to the consensus of the wise; therefore, o reader, you can trust and embrace it.” Such an ending is both a summary and a rhetorical sealing of the argument.

Another feature to note is the integration of quotations and references. While the text doesn’t explicitly footnote sources as we do today, it almost certainly weaves in quotations from the Bible (for authority) and perhaps uncited paraphrases of Church Fathers. The Latin Fathers like Augustine or Ambrose might be quoted verbatim. For instance, the author might include a line like “Omnia in mensura et numero et pondere disposuit Deus” (“God ordered all things in measure, number, and weight”), which is a direct biblical verse (Wisdom 11:21) much loved by Augustine – a succinct assertion of cosmic order. Such citations give the prose a textual richness; the intended audience (educated monks) would catch the allusions, much as one recognizes famous quotes, thus lending the work greater credibility and depth. In terms of stylistic tone, the author writes with a sense of wonder and reverence when talking about creation. Even as he explains scientifically, there’s an undercurrent of praise. This doxological tone is inherited from works like Basil’s Hexaemeron, where every explanation of nature turns into an occasion to glorify the Creator. We might see exclamatory phrases or syntactical emphasis that conveys marvel – e.g., “O ineffabilis Creatoris sapientia!” (“O the ineffable wisdom of the Creator!”) could be a plausible line in moments of reflection.

Clarity and Pedagogy: Despite occasional ornate sections, the treatise generally aims for clarity, as it is meant to instruct. The author organizes content methodically (day by day, topic by topic). He uses enumeration (first, second, third) to guide the reader through complex material. We see this even in how modern editors found it easy to divide into chapters – meaning the original likely had some internal markers of transition. The style avoids the extreme obscurity of some Hiberno-Latin experiments (like the Hisperica Famina which is deliberately obfuscating). Instead, it leans more towards the style of Isidore’s didactic prose or Bede’s prose – which, while elevated, remained intelligible. For example, when defining a term or explaining a concept, the author might use a simple appositive structure: “Terra enim, omnium elementorum infima, immobilis manet (reference)” (for instance) – a clause that defines earth as the lowest of elements that remains immobile. Such straightforward definitions are Isidore’s hallmark and likely present here too.

Use of Latin Language: The vocabulary mixes theological terms (Trinitas, persona, substantia, ordo, hierarchia perhaps) with scientific terms (elementum, firmanmentum, sphaera, eclipsim – Latinized Greek for eclipse, etc.). One can detect the influence of Latin translations of Greek works: words like antipodes (for people on the opposite side of the earth) or hemisphere might appear if the author dealt with the earth’s shape. The syntax might occasionally show Insular Latin quirks such as avoiding the classical structure in favor of one influenced by vernacular thinking. However, Irish Latin of the 7th century was still quite solid in its command of Classical grammar – these monks were trained on Latin texts. If anything, one might find some grammatical irregularities that became common in Medieval Latin (like confusion of subjunctive and indicative in certain clauses, or the use of et … et for “both…and” which is classical but medieval authors loved piling them).

In terms of manuscript evidence, scribes copying De Ordine Creaturarum in later centuries occasionally introduced marginal glosses or clarification of difficult words, indicating where the language may have been challenging. The Worcester manuscript mentioned encoded some lines, possibly also adding headings. By the Gothic script era (12th–14th c.), copies included chapter headings that were not originally there (reference). Those headings, while later additions, show how the medieval readers parsed the structure – likely titles like “De ordine angelorum,” “De ordine elementorum,” etc. This implies the text lent itself to sectional reading, which is a testament to its clear topical progression.

Overall Tone: The overall tone and style combine scholarly erudition with pastoral didacticism. The author writes as a teacher to his students (perhaps a monk writing for the instruction of other monks). He is thoroughly learned, as seen in his style and citations, but he’s also concerned that the reader understand and be edified. Thus, he balances the ornate with the instructional. By the end, the reader is left not only informed about the cosmos but also uplifted by a sense of the beauty and order instilled by God. The rhetorical and stylistic choices all serve that dual end: to teach the mind and move the heart toward praise. In essence, the linguistic and stylistic character of De Ordine Creaturarum exemplifies the best of early medieval Latin scholastic writing – grounded in classical tradition, enriched by biblical-patristic resonance, occasionally exuberant in expression, and invariably oriented toward conveying truth in an orderly, persuasive manner.

Concluding Note on Style: It is telling that centuries later, Charles W. Jones would call this work “a work of magnificent conception” (The Irish Background to the De XII abusiuis saeculi (Chapter 2) - Addressing Injustice in the Medieval Body Politic) – a phrase that not only lauds its content but also hints at the grandiosity of its style and structure. The text’s ability to communicate a “magnificent” vision of the cosmos is in no small part due to the author’s linguistic craft: he marshals Latin eloquence to paint an ordered creation. Readers with the requisite background (medieval monks or modern scholars of Latin) can appreciate the rhetorical artistry with which this anonymous master synthesized a world of knowledge into a flowing Latin treatise – a testament to the intellectual and literary vigor of early medieval scholarship.

Sources: The above analysis draws on modern scholarly evaluations and translations of De Ordine Creaturarum, notably the critical edition by Díaz y Díaz and the English translation and commentary by Marina Smyth, which illuminate the text’s context, content, and influence (reference) (reference) (reference) (The Irish Background to the De XII abusiuis saeculi (Chapter 2) - Addressing Injustice in the Medieval Body Politic). These sources help us understand how this 7th-century Hiberno-Latin work fits into the tapestry of medieval thought, bridging the patristic age and the scholastic era.

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube