Responsio de damnatione Salomonis (c.1150)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

A 12th-century theological treatise by Philip of Harveng addressing the controversial question of whether King Solomon was saved or damned, arguing that despite his wisdom and achievements, Solomon's unrepented idolatry in his later years led to his damnation—a moral warning about the necessity of perseverance in faith until death.

Authorship and Historical Context

The Responsio de damnatione Salomonis (Latin for “Response on the Damnation of Solomon”) is a 12th-century theological treatise written by Philip of Harveng (Philip of Harvengt), a Premonstratensian monk and abbot of Bonne-Espérance Abbey in Hainaut (in present-day Belgium) (Philip of Harveng - Wikipedia). Philip died in 1183, and his works show him to be an erudite monastic scholar. The Responsio was composed as a reply to an inquiry – Philip addresses his readers as “Queritis, fratres…” (“You ask, brothers…”) – indicating that fellow monks or clerics had posed a question regarding the fate of King Solomon. The question at hand was whether Solomon, King of Israel, should be considered saved or, as some argued, damned ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). This was not a trivial curiosity: Solomon’s case presented a theological puzzle in the Middle Ages because Solomon was revered for his God-given wisdom and achievements, yet Scripture recounts his grave sins in later life (notably idolatry induced by his many foreign wives, see 1 Kings 11). Medieval writers often extolled Solomon as a model of wisdom, justice, and divine favor, but they were also keenly aware of the “controversy about King Solomon’s holiness” ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). In a time when every major biblical figure’s moral and spiritual status was scrutinized for lessons and warnings, Solomon posed a paradox.

Philip of Harveng’s Responsio squarely addresses this paradox. It was likely written in the mid-12th century, during a period of vigorous biblical exegesis and theological debate in monastic schools. The treatise appears in Patrologia Latina vol. 203, alongside Philip’s other works, and it reflects the scholastic method of the age: posing a question and examining it through Scripture and the Church Fathers. Philip’s authorship is firmly established by medieval manuscript traditions and modern scholarship ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection), and the text survives in multiple manuscripts (e.g. Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale MS II.1156, and Paris, BnF n.a. lat. 1429) ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection). This indicates that the work circulated and was read by others, probably as a resource for understanding Solomon’s story. The historical context, therefore, is one of theological inquiry within the Church – the Responsio contributes to a long-running discussion on whether even the wisest of the Old Testament kings ultimately attained salvation or was condemned for his sins.

Theological Themes and Solomon’s Fate

At its core, Responsio de damnatione Salomonis grapples with the question of Solomon’s salvation or damnation. Philip’s analysis leans toward a dramatic conclusion: he argues that Solomon died in a state of sin and was damned, rather than saved (Philip of Harveng - The 4 Marks). This conclusion is built on several theological and scriptural observations:

-

Solomon’s Sin and Unrepentance: The treatise emphasizes the gravity of Solomon’s fall. In his old age, Solomon succumbed to idolatry – he worshipped the gods of his foreign wives. Philip underscores the unnatural perversity of this behavior, noting that while passion often inflames youth, in old age such lust should cool; yet “Solomon, when he was old and by the law of nature ought to have grown cold, burned with lust in a perverse way, and was so corrupted by love of women that he even followed their gods.” ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). This vivid description (drawn from the Responsio ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon) ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon)) highlights Solomon’s apostasy as a nearly unforgivable offense – the wisest king of Israel turned from Yahweh to idols. Crucially, Philip argues that Scripture provides no evidence that Solomon ever repented of this great sin. The Bible records King David’s repentance (Psalm 51) and God’s forgiveness of David, but for Solomon there is only silence. For Philip, this silence is ominous. If Solomon had repented, one would expect Scripture to mention it, as it does for other figures; the absence of any note of Solomon’s penance suggests he died unrepentant (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.). Thus, according to Philip, Solomon “did not repent for his sin” and therefore was not saved ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon).

-

The Weight of Scripture’s Testimony: The treatise weighs the good and bad in Solomon’s biblical portrayal. On one hand, Solomon is beloved of God (even named Jedidiah, “beloved of the Lord,” in 2 Samuel 12:25), renowned for wisdom (1 Kings 3-4), builder of the Temple, and author of sacred books (traditionally Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom). On the other hand, 1 Kings 11 recounts Solomon’s polygamy and idolatry, explicitly stating “the LORD became angry with Solomon, because his heart had turned away” (1 Kings 11:9). Philip acknowledges that “so many good and evil things are read of him in Scripture” that readers might not know which way to judge ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). His Responsio argues that the evil at the end of Solomon’s life must outweigh the earlier good, because final impenitence would nullify the merits of his earlier virtue. In essence, Solomon’s late-life apostasy is depicted as a conscious turning from God that, without repentance, leads to damnation – a moral lesson in the danger of failing to “persevere to the end.”

-

Solomon as a Cautionary Tale: A strong theme in the work is the moral warning derived from Solomon’s story. Philip of Harveng uses Solomon as an example of how even the most gifted and blessed person can fall into damnation through sin. The paradox of “the wisest man becomes the greatest fool” was not lost on medieval commentators. By asserting Solomon’s damnation, Philip effectively warns his audience that wisdom, knowledge, or divine favor are no guarantee of salvation – only steadfast fidelity to God’s law is. In this light, Solomon’s fate serves as a sobering reminder against complacency. As one summary phrase in the treatise puts it, “Solomon was a lover of women, and was rejected by God” ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). The theological message is that extraordinary privilege (Solomon’s wisdom and calling) will not excuse grave sin; God’s justice is impartial.

It’s important to note that not all medieval thinkers agreed with condemning Solomon. The very question Philip is addressing was controversial, meaning there were opposing interpretations. Some held out hope for Solomon’s salvation, proposing that he might have repented privately or that the book of Ecclesiastes is in fact Solomon’s repentant reflection on the vanity of his sins. Indeed, many Jewish and Christian interpreters historically believed Solomon did repent and be saved, citing that “Solomon’s way” after his death is spoken of honorably alongside David’s way (2 Chronicles 11:17) and pointing to Ecclesiastes as a kind of penance (where an aged Solomon proclaims the emptiness of his earthly indulgences) (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.) (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.). However, Philip of Harveng’s Responsio takes the opposite stance: it systematically refutes these optimistic readings. For example, if others argued that Ecclesiastes proves Solomon repented, Philip would counter that one cannot be certain Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes after his fall – the text itself doesn’t state that context. Philip anchors his case on what is explicitly revealed: the Bible narrates Solomon’s sin and does not narrate his repentance. Thus, in a strict canonical sense, Solomon’s story ends in disobedience, and Philip concludes that we must assume his damnation unless credible authority or scripture indicates otherwise (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.).

In summary, the Responsio’s major theological theme is the interplay of divine grace, human freedom, and the necessity of final repentance. It paints Solomon as a tragic figure who, despite unparalleled gifts from God, “did not persevere” in righteousness and so lost his reward. Philip’s interpretation underscores that final perseverance in faith is necessary for salvation – a key doctrine that one must persist in grace until the end, something Solomon failed to do in Philip’s view. Thus, the work uses Solomon’s fate to discuss broader issues of sin, repentance, and judgment.

Influence of Church Fathers and Patristic Sources

Philip of Harveng did not formulate his arguments in isolation; he was clearly informed by a tradition of Patristic commentary on Solomon. Throughout the Responsio, Philip either cites or echoes earlier Church Fathers to bolster his conclusions. The treatise in fact contains something of a “catena” (chain) of patristic opinions on Solomon’s sin and destiny ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection). This was typical of medieval theological method – authorities like Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory would be marshaled on either side of a question. Philip appears to have been well-versed in these earlier discussions:

-

St. Augustine’s Influence: Augustine of Hippo had considered Solomon’s fate in his writings, and Philip builds on Augustine’s reasoning ([PDF] The Words of Qoheleth, the Son of David, King in Jerusalem). In one source, Augustine poses the dilemma: “What shall we say of Solomon? Is he with God, or was he rejected after his idolatry? If we say he is with God, we seem to promise impunity to idolaters; but if we say he was rejected, we are stopped by God’s own word that for David’s sake He would not take the kingdom from Solomon…” (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”). Augustine thus saw ambiguity – leaning neither to fully acquitting nor condemning Solomon outright. Yet Augustine elsewhere strongly emphasizes Solomon’s sin. Philip picks up Augustine’s caution that Scripture does not explicitly mention Solomon’s restoration: “For scripture does not say that Solomon did penance or that he regained wisdom.” (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”) From Augustine (and writers influenced by him), Philip inherits the idea that in the absence of “positive evidence” of repentance, one must gravely regard Solomon’s fall. Augustine also commented on God’s promise to David (2 Samuel 7:14-15) – that God would chasten Solomon but not utterly withdraw His mercy. Some interpreted this to mean Solomon ultimately received mercy. However, Augustine and Philip interpret that promise as pertaining to the continuance of the kingdom (Solomon’s lineage and the Davidic throne), not necessarily the salvation of Solomon’s soul (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”) (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”). In fact, a phrase attributed to Augustine in a patristic compilation says of Solomon: “a seipso est depositus a regno”, that he *“was cast out of the kingdom by his own doing.” ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection) In other words, Solomon, by his sin, removed himself from God’s reign. This Augustinian idea buttresses Philip’s stance that Solomon’s loss was self-inflicted and definitive.

-

St. Jerome and Others: The Responsio likely references or draws from the opinions of Jerome, Ambrose, Bede, and possibly lesser-known fathers. A medieval catalogue of authorities on Solomon’s “prevarication and penitence” lists “our holy fathers Augustine, Jerome, Ambrose, [Isidore] and Bede” as commenting on the issue ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection). From St. Jerome, Philip would have known the importance of worshipping God alone – Jerome harshly criticized idolatry and could be cited to show the enormity of Solomon’s sin. Jerome in one letter remarks how even wise Solomon was seduced by women into folly, a point congenial to Philip’s argument. St. Ambrose similarly in his writings (like De Officiis) uses biblical figures as moral examples; Ambrose might have been quoted regarding the need for lifelong virtue. We see evidence that Philip’s treatise includes patristic quotes: for instance, a line in the Responsio reads “Salomon mulierum amator fuit, et reprobatus a Deo est” (“Solomon was a lover of women, and was rejected by God”) ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). This sounds like a distilled maxim from an earlier authority – possibly something St. Isidore of Seville or Venerable Bede wrote in a summary of biblical history. In fact, Bede (8th century) explicitly argued that Solomon never achieved repentance: Bede noted that Scripture does not depict Solomon doing penance as it does for David, and Bede took this as an indication that Solomon remained in sin (FROM EXEGESIS TO APPROPRIATION: THE MEDIEVAL SOLOMON). This view from Bede is directly aligned with Philip’s conclusion and would have given Philip a respected authority to cite in support.

-

Patristic Divergence: Not all Fathers agreed that Solomon was damned. Eastern Church Fathers and some Latin ones had a more sympathetic view. For example, in the East, it was common to list Solomon among the righteous kings (the Eastern liturgical tradition even celebrates Solomon on the Sunday of the Holy Forefathers). Latin writers like Cassiodorus or the author of the Glossa Ordinaria on the Bible compiled both sides: one gloss on 1 Kings acknowledges that if we condemn Solomon, we must reckon with God’s promise to keep mercy for him (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”). Some fathers, such as Origen (in a non-extant homily) or Rabanus Maurus, might have speculated that Solomon was saved by later contrition. We see a trace of a pro-Solomon argument in a patristic excerpt: “It is clear, then, that Solomon is with God; for David’s sake, not even his earthly kingdom was taken away… Solomon was a figure of the bipartite Church… his wisdom was vast, and his idolatry terrible.” (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”) (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”). This allegorical reading (possibly from a Carolingian commentary) interprets Solomon mercifully as ultimately “with God,” making him an image of both the wise and sinful Church that still finds grace. Philip of Harveng was certainly aware of such interpretations – indeed, he takes care in his treatise to address them respectfully. He insists that his negative conclusion is not born of ill will: “I must shore up what I have said, lest perhaps I appear envious of Solomon’s salvation, and on that account twist the Scriptures to my own wish presumptuously rather than truthfully.” ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). This frank statement shows Philip defending himself against the charge of being too severe on Solomon. By “shoring up” his argument with Scripture and Fathers, he wants to prove that it’s not personal bias (“envy” of Solomon’s salvation) but the weight of authoritative testimony that leads him to conclude Solomon was lost.

In essence, Philip’s Responsio functions as a synthesis of patristic wisdom on Solomon, aligning primarily with those voices (Augustine, Bede, Isidore) that emphasize Solomon’s failure to repent. He respectfully acknowledges the contrary voices but ultimately refutes them. The influence of the Church Fathers is thus central: Philip uses their authority to lend credence to the stark idea that a famed biblical king might be damned. This patristic grounding gave his medieval readers confidence that he was not introducing novel ideas, but rather transmitting the consensus of venerable teachers – even if, in truth, the Fathers themselves had varied opinions, which Philip selectively interprets in favor of damnation.

Reception History and Impact

The question of Solomon’s fate did not end with Philip of Harveng’s treatise; it continued to percolate in medieval theological discourse, and the Responsio itself became a reference point in that ongoing conversation. Some key aspects of its reception and impact include:

-

Manuscript Circulation: The survival of the Responsio de damnatione Salomonis in multiple manuscripts suggests it was read and valued in monastic and scholastic circles. It was likely used as a resource for biblical studies – possibly read during the training of young clerics when discussing the Book of Kings or moral lessons from the Old Testament. The treatise, being a self-contained argument on a specific question, could have been excerpted or summarized in encyclopedic works. In fact, around the same period, Lambert of St. Omer compiled the Liber Floridus (early 12th century), an encyclopedia of sorts, which in one chapter includes a section on the “Penitence of Solomon” with quotes from Church Fathers ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection) ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection). By the second half of the 12th century, Alexander Neckam, an English scholar, wrote a biblical commentary that also discussed Solomon’s fall and supposed penitence, again assembling patristic snippets. A study of these works shows that Philip of Harveng’s Responsio contained a patristic catena quite similar to what Neckam and Lambert presented ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection). This implies that Philip’s treatise either influenced these compilations or drew from common sources that were circulating. In either case, Responsio became part of the broader medieval tradition tackling Solomon’s story.

-

Classroom and Scholastic Debates: During the 12th and 13th centuries, theologians frequently engaged in “quaestiones” – structured debates on theological questions. The fate of certain biblical figures (Solomon, Samson, Origen, Judas, etc.) were popular quandaries. The Responsio would have provided arguments and authorities for one side of the question (“Solomon was damned”). It likely informed discussions at schools like those of Paris. Indeed, the Glossae Ordinariae (standard Bible gloss) on 1 Kings and the Sentences of Peter Lombard (1150s) both mention Solomon’s sin. While Peter Lombard does not definitively resolve Solomon’s fate in the Sentences, he raises the issue of grave sinners in the Old Covenant. The lack of a firm stance in such a foundational textbook meant the debate was open for commentators like St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century to weigh in. (Aquinas, notably, in his Summa Theologiae cites Solomon as an example of someone who received great gifts but fell; he stops short of declaring Solomon damned, but he underscores that final perseverance is a special gift, implicitly suggesting Solomon did not have it.) Thus, Philip’s hard-line conclusion stood as one influential opinion that later scholars had to acknowledge even if they chose a more guarded position.

-

Medieval Drama and Literature: The figure of Solomon also appeared in medieval literature and sermons. It’s worth noting that in some medieval mystery plays and sermons, Solomon is portrayed as a warning example. The impact of treatises like Philip’s can be sensed in these cultural artifacts – preachers would mention how even Solomon was lost because of lust and idolatry, driving home the moral that lineage or knowledge won’t save a soul lacking obedience. On the other hand, there were also more harmonizing interpretations in literature: for example, the Cursor Mundi (a 14th-century English religious poem) tries to reconcile Solomon’s wisdom with his folly, sometimes by allegory (Solomon representing the divided church, etc.). This reflects that the question invited creative responses. The Responsio did not close the book on Solomon, but it supplied a definitive viewpoint that had to be considered.

-

Later Theological Debates: By the late Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, explicit debate on Solomon’s personal salvation waned, but the underlying doctrinal issues (like perseverance and repentance) remained crucial. During the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, the question surfaced indirectly. Protestants, emphasizing the assurance of the elect, often contended that biblical authors and true believers – Solomon included – ultimately were saved by God’s grace. For instance, John Calvin, while acknowledging Solomon’s severe fall, leaned toward the idea that Solomon was restored (Calvin saw Ecclesiastes as evidence of repentance). Catholic Counter-Reformers, conversely, warned that Solomon’s example showed the possibility of falling from grace, supporting the Catholic doctrine that one can lose salvation through mortal sin. In this context, Philip’s conclusion found a new resonance: it underscored the Catholic teaching that no one is predestined to glory without cooperation and perseverance. There is even an interesting side note: Philip’s Responsio touches on the canon of Scripture in passing – he only considers canonical texts in making his argument. In doing so, he apparently affirms the traditional (Hebrew) canon by excluding, for example, the deuterocanonical Wisdom of Solomon (which portrays Solomon righteously) from authoritative evidence (Bishop Peter Cellenis, in his writing “De panibus ad Joannem …). This detail was later picked up by scholars noting that Philip listed the books of Scripture read in the canon and omitted those like Sirach, Tobit, Judith, aligning with what Protestants centuries later called the “shorter canon.” While Philip was simply following the common Norman/Paris canon of his day, this point shows how a medieval treatise can later intersect with different debates (here, the Reformation-era canon debate).

-

Influence on Art and Devotion: Solomon’s image in medieval art was ambivalent – sometimes he is depicted enthroned in glory as a wise king (often in contexts emphasizing his wisdom as a precursor to Christ’s wisdom), and other times artists included scenes of his idolatry as a caution. In illuminated manuscripts and cathedral sculpture, Solomon might appear in a Tree of Jesse (ancestry of Christ) as a noble figure, but in moralizing contexts (like psalters or Books of Hours illustrating the Penitential Psalms), one finds scenes of Solomon’s wives turning his heart. A notable example is a Parisian Book of Hours (c.1500) where an illumination for Psalm 51 shows Solomon enthroned with women cajoling him at the top, and prophets lamenting below – a direct visual teaching that Solomon’s lust led to his spiritual downfall (Solomon’s Idolatry - VCS) (Solomon’s Idolatry - VCS). This reflects the same lesson that Philip of Harveng pressed in prose. Thus, the Responsio’s perspective fed into the reception history of Solomon as primarily a moral lesson of warning in the Western Christian mind.

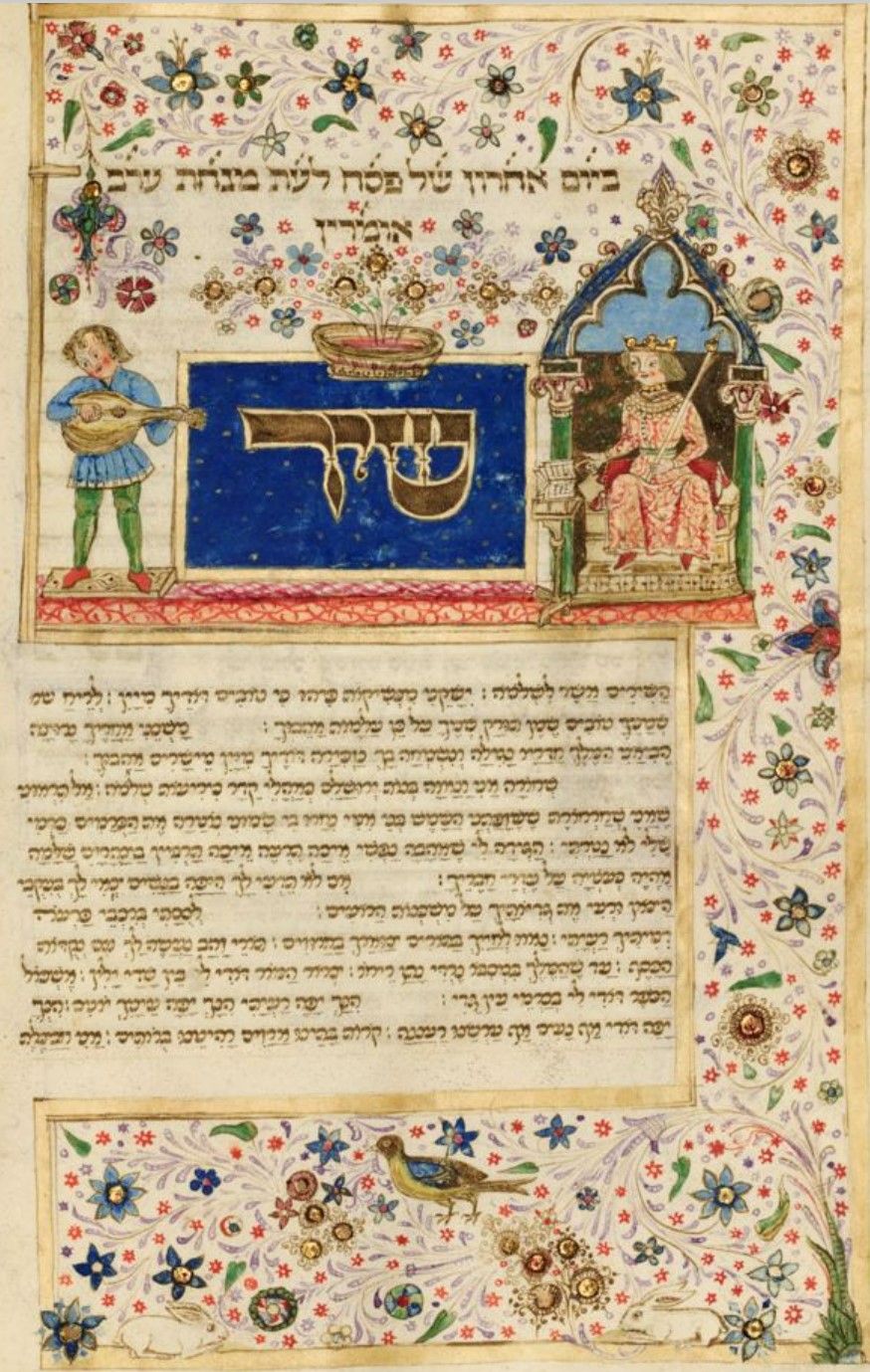

Figure: Late-medieval depiction of King Solomon enthroned (right) with a musician before him. Solomon’s grandeur and wisdom (he is often shown in royal dignity) were contrasted with his tragic end; in theological debates of the Middle Ages, he became a prime example of a soul that squandered God’s grace (Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng) (Philip of Harveng).

In summary, Philip’s Responsio de damnatione Salomonis had a significant if specialized impact: it became part of the medieval scholarly canon on Scriptural problems, was cited or echoed by subsequent commentators, and contributed to the portrayal of Solomon in preaching and art as a sobering caution. By the time of the Renaissance, the view of a damned Solomon coexisted with more charitable views. The question was never definitively resolved by Church authority, which is why even today one finds different opinions among scholars and theologians – a testament to a debate that Philip of Harveng helped shape in the 12th century.

Doctrinal and Moral Relevance

Beyond the fate of one biblical king, the Responsio engages with broader doctrinal issues and has implications for theological concepts of its time (and beyond). Key themes and their doctrinal significance include:

-

Salvation and Final Perseverance: The case of Solomon is essentially used to discuss the importance of persevering in faith and grace until the end of one’s life. Philip’s analysis underscores that initial salvation or divine favor can be lost. Solomon was dearly loved by God and endowed with wisdom – in modern terms, we might say he was “in God’s grace” for much of his life – yet he fell away. This illustrates the Catholic doctrine that one can indeed lose the state of grace by mortal sin. It refutes any idea of an absolute guarantee of salvation irrespective of one’s later choices. Medieval theologians saw in Solomon a counter to presumptions of security: as one 17th-century commentator later put it, Solomon’s example shows that even “a true spiritual child of God” can fall if he does not persevere (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.) (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.). The Responsio thereby highlights the doctrine of final perseverance: the greatest of God’s gifts which Solomon, tragically, did not attain. For the audience, the moral was clear – one must strive to be faithful lifelong, “for he that shall persevere to the end shall be saved” (Matthew 24:13).

-

Necessity of Repentance: A closely related theme is the absolute necessity of genuine repentance for grave sin. Solomon’s sin was idolatry, a mortal sin that breaks one’s relationship with God. Without repentance, such sin leads to damnation. Philip’s insistence that Solomon did not repent and thus was lost ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon) is a doctrinal point: it reinforces that God’s forgiveness is contingent upon repentance (at least ordinarily; apart from unknown divine mysteries). This has pastoral weight – it warns believers that one cannot count on God’s indulgence if one refuses to turn back to Him. The fact that Solomon possibly had many years at the end of his life to repent, yet (as Philip sees it) did not, makes his fate a tragic caution: postponing repentance or persisting in sin can result in a hardened heart and a missed opportunity for salvation. It aligns with the Church’s teaching on free will – Solomon was not predestined to damnation; rather, he chose not to humble himself in repentance, and thus he was justly condemned. The text thus would exhort readers to practice examination of conscience and penance, lest they follow Solomon’s path.

-

Divine Justice and Mercy: The Responsio navigates the tension between God’s justice and God’s mercy. One might ask: was it just for God to condemn Solomon after all the good he had done? Philip’s answer is essentially yes. Divine justice repays each according to their deeds at the end. Solomon’s end was filled with apostasy, so justice demands condemnation. However, the treatise also addresses God’s mercy in the form of the promise made to David about Solomon (2 Samuel 7:14-15). God promised not to withdraw His favor entirely despite Solomon’s sins – “My mercy shall not depart from him, as I took it from Saul” was the divine word to David. How is this reconciled with Solomon being “reprobatus a Deo” (rejected by God) as Philip claims? The reconciliation offered is that God kept His mercy in a temporal and covenantal sense – He did not strip Solomon of the kingship during his life, for the sake of David and the future Messianic plan (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”). Solomon’s dynasty continued (unlike Saul’s, which ended). In other words, God’s merciful promise was about not utterly cutting off David’s line; it was not an unconditional guarantee of Solomon’s personal salvation. This distinction upholds God’s justice: morally, Solomon still faced the consequences of his own choices. Thus, Philip’s argument illustrates a doctrinal nuance: God can be faithful to His promises (showing mercy in one sphere) while still exercising judgment in another. There is also an eschatological angle – some theologians later suggested perhaps Solomon might have been given a chance to repent at death or even after (a stretch not found in Philip). But Philip’s view implies no – after death, the time of mercy is past, and Solomon faced judgment. This reinforces standard teaching on judgment and the afterlife.

-

Authority of Scripture and Tradition: The debate around Solomon also had a methodological or epistemological dimension. It taught medieval scholars how to handle Scripture’s silence. Philip’s approach – to argue from the silence of Scripture about repentance – shows one way of deriving theological conclusions (often termed an argument from omission). Not all agreed this was a firm ground, and indeed another school of thought cautioned against building doctrine on what Scripture does not say (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.). But Philip buttressed his case with the weight of patristic tradition, effectively combining Scripture and Tradition to reach a conclusion. This is doctrinally significant as it exemplifies the Catholic approach: even in ambiguous matters, the consensus of venerable teachers (like Augustine and Bede) can guide interpretation. Furthermore, as noted, Philip only used canonical Scripture to argue the case – books whose authority was undisputed. This avoided complications; for example, the deuterocanonical Wisdom of Solomon depicts Solomon as devout, but Philip did not rely on that text, possibly considering it outside the Hebrew canon. This choice reflects the medieval uncertainty about those books, and inadvertently, it meant Philip’s argument resonated later with Protestant readers who also prioritized the Hebrew canon. In any case, the doctrinal stance is that Scripture is sufficient to teach moral truth, and if Scripture presents Solomon’s life as a warning, that didactic purpose might be why his repentance was not recorded (some commentators suggested Scripture left Solomon’s fate open as a deterrent to sinners, so that people fear the worst and avoid sin) (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.). Philip’s conclusion aligns with that pedagogical aim: believing Solomon was damned makes his story a stronger deterrent against falling away.

-

Contemplation of Divine Mystery: A subtle theological aspect of the Responsio is how it invites reflection on the mystery of God’s judgments. Why would God grant so much wisdom and grace to Solomon, knowing he would fall? Medieval theologians like Philip would answer that God’s gifts are free and can be squandered by human misuse – it displays God’s magnanimity and man’s responsibility. Moreover, Solomon’s fall, while tragic for him, serves the larger divine pedagogy for others. It also raises the notion (later discussed by theologians) that election in the Old Testament was often about role or office (Solomon as king and ancestor of Christ) rather than guaranteed personal salvation. This distinction foreshadows later doctrinal clarity that being chosen for a task (like being Israel’s king) is not the same as the gift of final salvation – one must still cooperate with grace. In Solomon’s case, he fulfilled his God-given office (built the Temple, continued David’s line), but failed in personal fidelity. This helps resolve the cognitive dissonance of a God-loved figure being lost: it emphasizes human freedom and the multi-faceted nature of God’s plan (historical vs. personal). Thus, doctrinally, the Responsio reinforces that God desires all to be saved, gives sufficient grace, but does not override human freedom – Solomon is an example of a richly graced person who freely chose ruin.

In moral and devotional terms, the figure of Solomon as portrayed by Philip’s treatise had one overriding purpose: to educate consciences. Just as Solomon’s wisdom did not prevent folly, the faithful are reminded that knowledge of God’s law is not enough – one must love God and obey. Just as Solomon’s status did not grant him immunity, no one should presume upon their standing (be it as a cleric, a baptized Christian, etc.) to excuse sin. The text stresses humility: if Solomon fell, any of us can, absent God’s sustaining grace. In sum, the doctrinal threads running through Responsio de damnatione Salomonis – free will, necessity of perseverance, conditional nature of salvation – are ones that remain central in Christian theology. The work encapsulates these in a vivid historical example, making abstract principles tangible through the rise and fall of a famous king.

Controversies and Later Reflections

While Responsio de damnatione Salomonis did not spark a heresy trial or an official condemnation – it stayed within acceptable bounds of theological opinion – it did stir debate and even a bit of discomfort among some thinkers. Calling King Solomon “damned” was provocative in that Solomon was a scriptural author and traditionally revered. Here are some aspects of the controversial edge and legacy of the text:

-

Tension with Solomon’s Image as Saintly King: Particularly in the Eastern Christian tradition, Solomon (along with David) is counted among righteous Old Testament figures. Even in the West, he was often seen as a type of Christ (for his wisdom and kingship) or at least as someone who, like his father David, might have found mercy. Philip’s stark pronouncement thus cut against a certain pious instinct to see the famous kings of Israel in heaven. This likely provoked some pushback in learned circles. We see evidence of this in how carefully Philip words his argument so as not to appear “presumptuous” or spiteful regarding Solomon’s soul ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon). The fact that he anticipates criticism suggests that some contemporaries would have indeed thought it rash or impious to conclude a biblical icon was damned. The controversy, therefore, was mostly an intellectual one: Was it right to judge Solomon in this manner, or should one suspend judgment?

-

Moderate Voices Urging Caution: In the generations after Philip, more ironic or cautious voices emerged regarding such questions. For instance, Nicholas of Lyra (a 14th-century biblical commentator) when commenting on Solomon, effectively said that since Scripture is not explicit, and the question does not affect the core of our salvation, one need not reach a dogmatic conclusion (14 The Four “Senses” and Four Exegetes - Oxford Academic). This temperament likely arose because of the uneasy feeling that declaring Solomon damned might mislead or scandalize some (for example, if Solomon is in hell despite being beloved of God once, what of us?). Nicholas and others leaned on the idea that the church does not definitively declare the damnation of individuals apart from known cases like the biblical figure of Judas Iscariot. Indeed, except for Judas, very few if any specific individuals are doctrinally taught to be in hell – the Church typically leaves that knowledge to God. Solomon’s case, while debated, never reached a point of doctrinal definition. Thus some later theologians might critique Philip’s stance as going a bit beyond what can be safely asserted. The Responsio remained a permissible view, but not a required one.

-

Potential Controversy in Canonization and Liturgy: Interestingly, if one considered Solomon a reprobate soul, it would affect how one treats his memory liturgically. In the Western Church, Solomon was never canonized as a saint (unlike some prophets); there is no feast of “St. Solomon King.” This made Philip’s argument easier to maintain, since there was no official cult or liturgical texts venerating Solomon in the West. (The Eastern Orthodox do commemorate Solomon as a saint on the Sunday of the Forefathers, which is an intriguing contrast – a sign of differing emphasis.) Had there been any Western saintly cult for Solomon, Philip’s thesis would have been outright controversial. As it stood, it challenged a generally positive but not officially dogmatic view of Solomon. We do see late-medieval authors like Voltaire (18th century, much later) noting wryly that “several fathers say that Solomon did penance, so that we can pardon him” (The Works of Voltaire, Vol. VII (Philosophical Dictionary Part 5)) – indicating that by the Enlightenment, the question was still remembered and people knew there was no unanimous answer among the Fathers.

-

Enduring Fascination: The legacy of Philip’s Responsio can be traced in how the figure of Solomon is taught even into modern times. The question “Did Solomon repent before he died?” is still posed by readers of the Bible. Modern scholars might reference Philip of Harveng as one of the earliest to thoroughly take the negative position. While today’s academic approach doesn’t consider his view determinative, it acknowledges the historical impact: Philip’s treatise encapsulated a stream of tradition that viewed Solomon as a tragic caution. In doing so, Philip contributed to a kind of de-mystification of biblical heroes – an approach that is actually quite in line with the Augustinian idea that even great figures can fall (Augustine famously said of biblical saints, “God did not spare them because of their merit, but condemned what was evil in them”). This level-headed, morally stringent reading helped shape medieval exegesis into a deeply ethical exercise.

In conclusion, Responsio de damnatione Salomonis stands as a noteworthy medieval examination of Scripture and morality. Its assertive conclusion – that King Solomon was damned for lack of repentance – provoked thoughtful engagement with themes of sin and grace. Though not without its detractors and alternative viewpoints, Philip of Harveng’s work carved out a place in theological history. It exemplifies the medieval commitment to take even the most illustrious biblical personalities as subjects of analysis and lessons for the soul. Through it, Solomon’s grandeur is remembered with an asterisk: wisdom is no defense in the absence of humility. This message, controversial or not, resonated through the medieval period and invites later generations to ponder the always relevant spiritual question: “What does it profit a man to gain the whole world (or all wisdom) and lose his own soul?” Solomon’s story, as interpreted by Philip of Harveng, emphatically warns that it profits nothing – a man is lost without fidelity to God, even if he was once the wisest on earth.

Sources: Primary text from Patrologia Latina 203 (Philip of Harveng) ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon) ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon); analysis by Anabela Katreničová (2017) on Solomon’s damnation controversy ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon) ((PDF) Responsio de damnatione Salomonis de Philippe de Harveng: Une étude médiévale sur la damnation du roi Salomon); biographical details from Premonstratensian archives (Philip of Harveng - The 4 Marks); biblical commentary tradition (e.g., Matthew Poole’s Commentary) illustrating arguments on Solomon’s repentance (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.) (1 Kings 11:43 Commentaries: And Solomon slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of his father David, and his son Rehoboam reigned in his place.); patristic excerpts (Augustine, Bede) as compiled in a history of interpretation (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”) (Full text of “History of Biblical Interpretation. A Reader”); and contextual information on manuscript transmission ((PDF) Pseudepigrapha Notes III: 4. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in the Yale University MS Collection).

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube