Contra Graecorum Opposita (c.868)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

Latin text and English translation of Ratramnus of Corbie's influential 9th-century treatise defending Western Christianity against Byzantine criticisms during the Photian Schism, offering sophisticated arguments for the Filioque doctrine, papal primacy, and the legitimacy of Latin liturgical practices while distinguishing between essential matters of faith and acceptable diversity in customs.

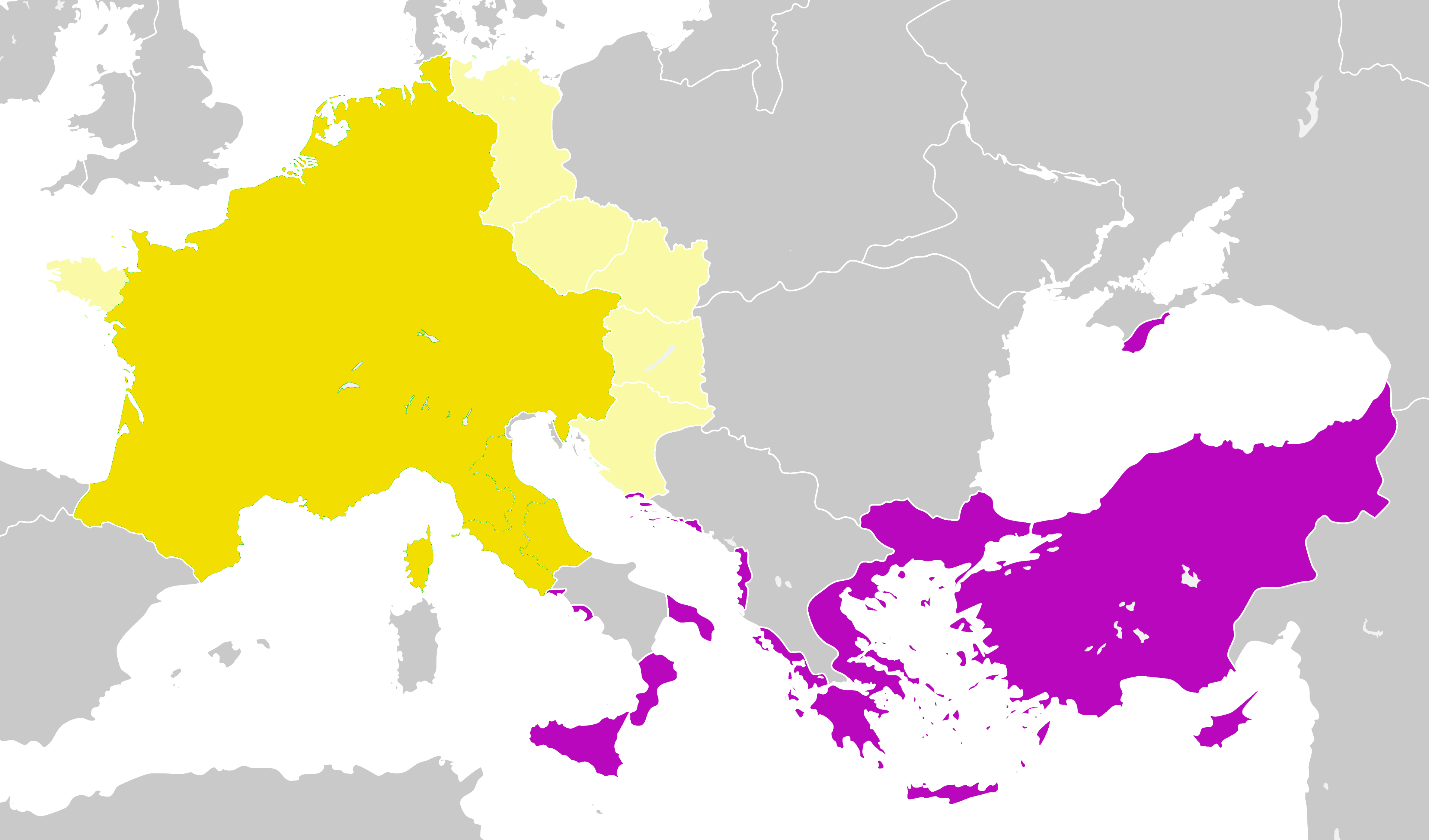

Map showing the Carolingian (Western Latin) Empire (yellow) and the Byzantine (Eastern Greek) Empire (purple) in the early 9th century. This geopolitical split underpinned the cultural and ecclesiastical differences that Contra Graecorum Opposita addresses (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library) (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia).

Map showing the Carolingian (Western Latin) Empire (yellow) and the Byzantine (Eastern Greek) Empire (purple) in the early 9th century. This geopolitical split underpinned the cultural and ecclesiastical differences that Contra Graecorum Opposita addresses (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library) (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia).

Historical Context

Author and Setting: Contra Graecorum Opposita (“Against the Oppositions of the Greeks”) was written by Ratramnus of Corbie, a 9th-century Carolingian monk-theologian. Ratramnus was a Benedictine monk at Corbie Abbey in Frankish Gaul (modern France), known for his independent mind and scholarly acumen (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com) (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com). He lived during the reign of King Charles the Bald and participated in the Carolingian renaissance of learning. Ratramnus’s other works (on the Eucharist and predestination) show him engaging major theological debates of his day (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com) (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com). He composed Contra Graecorum Opposita around 868 AD, likely at the request of Latin bishops (the province of Reims under Archbishop Hincmar) (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia).

East–West Tensions: The treatise arose from intense East–West Church controversies in the mid-9th century. In 863–867, a dispute known as the Photian Schism erupted between Rome and Constantinople (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library). Patriarch Photius I of Constantinople (with Emperor Michael III’s backing) had challenged Pope Nicholas I on multiple fronts – both theological and jurisdictional. A key flashpoint was the competition over newly Christianized Bulgaria, where both the Byzantine and Frankish missionaries vied for influence (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia). Photius, to discredit the Roman missionaries, circulated an encyclical letter (867) cataloguing what he deemed Latin errors. With imperial support (Emperors Michael III and Basil I), these “opposita” – accusations against the Roman Church – were spread to defame Latin practices as “false, heretical, superstitious, or irreligious” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). Among the charges: that the Latins had altered doctrine (especially regarding the Holy Spirit), and followed illicit customs (from fasting days to clerical celibacy). Pope Nicholas I reacted by urging the Frankish theologians to mount a united defense of Latin orthodoxy (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com). It was in response to this call that Ratramnus penned Contra Graecorum Opposita, making it “a valued contribution to the controversy between the Eastern and Western Churches” (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library). In effect, the work is Ratramnus’s answer to Photius’s anti-Latin manifesto, written to uphold the unity of faith between Rome and Constantinople despite differences, and to vindicate the Latin Church against Byzantine criticism (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com) (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia).

Controversies Addressed: The text engages both theological and politico-ecclesial issues of its time. Theologically, it intervenes in the developing East–West divergence on the Nicene Creed’s wording (the Filioque clause) and related doctrines of the Trinity (Ratramnus - Britannica). Politically, it touches on the question of papal primacy versus the autonomy of Eastern patriarchs, an issue sharpened by Rome’s condemnation of Photius’s irregular elevation to the patriarchate. There were also cultural and liturgical differences at stake – e.g. Western vs Eastern fasting practices, clerical marriage discipline, and liturgical rites – which had taken on polemical significance. Ratramnus wrote at a moment when the Latin West, under Nicholas I and the Carolingian princes, was asserting its theological positions and ecclesial authority, while the Byzantine East, under Photius and the emperors, was pushing back. Thus, Contra Graecorum Opposita is best understood against the backdrop of the first major rupture between Latin and Greek Christianity (a prelude to the later Great Schism of 1054), reflecting the Carolingian-Franks’ effort to defend Latin orthodoxy and heal the breach through reasoned argument (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library) (Ratramnus - Britannica).

Theological Arguments

Latin Doctrine vs Greek Objections: Ratramnus’s work systematically answers the “opposita” (objections) raised by Photius and the Byzantine court. It is structured in four books, each tackling major points of dispute. Throughout, Ratramnus argues that the Latin Church’s faith is orthodox and in continuity with the early Church, and that many East–West differences are in non-essentials (customs) rather than core doctrine (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). The primary doctrinal debates he addresses include:

-

Procession of the Holy Spirit (Filioque): This was the central theological issue. Photius had accused the Latins of heresy for adding “Filioque” (“and the Son”) to the Creed’s article on the Holy Spirit. In response, Ratramnus delivers an extensive defense of the double procession of the Holy Spirit from Father and Son, upholding the West’s position. Over the first three books, he marshals impressive biblical and patristic evidence to show that this teaching is rooted in the Catholic faith and the Church Fathers’ testimony (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com). For example, he cites Christ’s promise of the Paraclete (“the Spirit of truth, whom I will send to you from the Father” – John 15:26) as evidence that the Son has a role in sending forth (and therefore in the eternal procession of) the Spirit (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). He also quotes St. Peter’s words in Acts 2:33 (Jesus, exalted at God’s right hand, “has poured out the Spirit”) to argue that “both the Father and Jesus Christ” bestow the Spirit, implying the Spirit proceeds from both (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). Ratramnus accuses the Greek theologians of novelty and even heresy on this point – noting that the Greek Fathers never outright denied the Son’s participation in the Spirit’s procession (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). He boldly claims the opponents “condemn themselves by the depravity of heresy” and “blaspheme against the Holy Spirit” by rejecting the Filioque (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). By citing earlier authorities (like St. Augustine and other Fathers revered in East and West), he contends that the “one essential faith” of the universal Church includes the belief that the Spirit is the Spirit “of both Father and Son.” In essence, Ratramnus positions the Latin understanding as consistent with Scripture and tradition, urging the Greeks to follow the consensus of their “own ancestors” who, he asserts, implicitly acknowledged the Filioque truth (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). This robust Trinitarian argument – learned and heavily footnoted with patristic references – is presented as the “first and chief” matter, foundational to Catholic faith (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource).

-

Papal Primacy and Church Authority: Another major doctrinal issue was the authority of the Roman See. Photius’s polemic had challenged the Pope’s primacy, especially given Rome’s interference in Constantinople’s affairs. Ratramnus devotes the fourth book to upholding Roman primacy and the Petrine foundation of the Church (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia). He invokes Christ’s words to Peter (“Tu es Petrus, et super hanc petram aedificabo Ecclesiam meam” – Matt. 16:18) to affirm that the Roman Church, as Peter’s successor, holds a place of preeminent authority (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). With some originality, he argues that unity under Rome’s guidance is crucial for the Church’s catholicity (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com). At the same time, he rebukes the Byzantine emperors for meddling in spiritual matters: Ratramnus pointedly reminds readers that doctrinal disputes are the realm of bishops, not emperors, citing the Old Testament story of King Uzziah who was punished with leprosy for usurping priestly functions (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). This underscores his view that the Pope and bishops (not secular rulers) are the guardians of orthodoxy. By defending papal primacy, Ratramnus also implicitly justifies Pope Nicholas’s stance against Photius. He portrays the Roman Church as maintaining unchanged the apostolic faith and ancient customs, deserving respect rather than the censure of “upstart teachers” in Constantinople (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource).

Customs and Liturgical Practices: Beyond doctrine, Contra Graecorum Opposita addresses a host of ritual and disciplinary differences that the Greeks had criticized. Ratramnus makes a clear distinction between core faith (where unity is mandatory) and customs or rites (where diversity can be permissible) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). He defends the Latin Church against charges of “superstition” or “irreligion” in its practices, showing that many are rooted in apostolic or patristic precedent. Key points of contention included:

-

Fasting Practices: The Greeks objected that Latins fast on the Sabbath (Saturday) and follow a different rule for the Paschal fast (Lent). In the East, Saturday (except Holy Saturday) was not a fast day, whereas in the West it often was. Ratramnus responds with a bit of wit: if fasting is good, why blame Latins for doing it, and if it is bad, why do Greeks themselves fast at other times? (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) He notes that this criticism is inconsistent and rooted in “pride or ignorance.” He even cites a tradition that the apostles Peter and Paul fasted on a Saturday before confronting Simon Magus, from which the Roman Church adopted Saturday fasting (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). Thus, the Latin practice is portrayed as ancient and edifying, not an innovation. Differences in liturgical calendar (such as the timing of the Lenten fast or the calculation of Easter) are, for Ratramnus, variations of discipline that do not touch the substance of faith.

-

Bread of the Eucharist & “Judaizing” Rituals: Photius’s party accused Latins of Judaizing practices – for example, an odd claim that Latins place a “lamb” on the altar at Easter “in the manner of the Jews” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). This likely referred to the Western use of unleavened bread (azymes) in the Eucharist or the blessing of an Easter lamb cake/figurine. Ratramnus flatly calls this charge a falsehood and slander. “Do they not clearly lie?” he exclaims, pointing out that no such literal lamb sacrifice is part of Roman liturgy (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). By refuting this, he defends the Latin use of unleavened bread (if that is what the Greeks misconstrued) as perfectly valid – after all, Christ used unleavened bread at the Last Supper, so the practice can hardly be called irreligious. Ratramnus’s indignation at this accusation underscores that some Greek criticisms were based on misinformation or propaganda.

-

Clerical Celibacy vs Marriage: Another sensitive issue was the Western insistence on clerical continence (priests not marrying or refraining from marital relations after ordination). The Eastern Church allowed married men to serve as priests (though bishops were celibate monks), and Photius portrayed the Latin stance as a “condemnation of marriage” or an undue harshness. Ratramnus vehemently rejects the idea that valuing celibacy means despising marriage (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). He praises clerical continence as a holy tradition dating to the apostles, aimed at greater purity in serving the altar (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). While acknowledging that marriage is good in itself, he argues it is “inappropriate for priests to marry” due to the spiritual distractions and “ritual impurity” that marital life could entail (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage). In a striking move, Ratramnus even cites the Council of Nicaea (325) as support: he quotes its canon forbidding clergy to have any unrelated women in their household (to avoid scandal) and reasons that this effectively forbids having a wife – since a wife inevitably brings other women (servants, etc.) into the household (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage). (Modern historians note that Nicaea did not actually ban clerical marriage – Ratramnus is likely misinterpreting it (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage). Nonetheless, his use of Nicaea shows his determination to claim the highest patristic authority for the Latin discipline.) By these arguments, he turns the tables: rather than the Latins being against marriage, the Greeks are portrayed as lax by allowing clergy to marry, contrary (in his view) to the mind of the early Church. This is one area where Ratramnus is especially uncompromising – he treats clerical celibacy as an ancient norm that underscores the sacredness of the priesthood.

-

Liturgical Roles (Chrismation) and Customs: Photius had also criticized that in the West, priests do not anoint the baptized with chrism on the forehead, reserving that for bishops (confirmation), and he mocked the Western shaving of beards (since Eastern clergy kept full beards). Ratramnus responds that these are trivial matters elevated to undue importance. “Who cannot see how ridiculous it is,” he writes, to blame us for shaving? (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) There is no divine law, he notes, either commanding beard-growing or forbidding it – it’s a mere custom with no bearing on salvation (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). As for post-baptismal anointing, Ratramnus explains that Western priests do baptize validly by triple immersion and invocation of the Trinity, and they do anoint the baptized with oil consecrated by the bishop – they simply leave the signing of the forehead (the confirmatio) to the bishop as a special mark of the bishop’s ministry (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). This, he argues, in no way nullifies the grace of baptism; it’s a disciplinary choice that actually honors the episcopate’s dignity. He backs this up by referencing practices of the early Church (indeed, the Acts of the Apostles 8:14–17, where only the apostles Peter and John laid hands on Samaritan converts to impart the Holy Spirit) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). Thus, the Latin custom is shown to align with Scripture and ancient tradition. Ratramnus labels the Greek obsession with such externals as “superstition, not any religious consideration” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) – implying the Greeks were straining out a gnat while swallowing a camel. In summary, he insists that none of these Latins customs are heretical or impious; at most, they are legitimate variations in church practice. The unity of faith, he asserts, can accommodate different rites or disciplines.

Throughout these arguments, Ratramnus consistently returns to a core thesis: doctrinal unity is paramount, while liturgical diversity can be tolerated. He notes that East and West “have always remained in the same faith… One faith, one baptism”, even though local “institutions of the elders” and customs varied from region to region (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). In earlier ages, such differences “in habit or way of life” never broke the communion between churches (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). By highlighting this, Ratramnus appeals to the Greeks to not let non-essential differences (like beard-shaving or fasting days) rend the fabric of Church unity. At the same time, on truly essential matters (like the Trinity and the authority of Rome), he holds a firm line, urging the Easterners to correct what he sees as their errors for the sake of reunion. This balanced approach – unyielding on doctrine, irenic on custom – is a defining feature of his theological argumentation.

Linguistic and Stylistic Analysis

Latin Style and Rhetoric: Contra Graecorum Opposita is not only rich in content but also notable for its Latinity and rhetorical craft, to the point that scholars consider it Ratramnus’s finest work “from a literary as well as a dogmatic standpoint” (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia). The Latin style is characteristic of the Carolingian renaissance: clear and learned, consciously modeled on patristic and biblical language. Ratramnus writes in a scholarly yet polemical tone, using classical rhetoric to drive home his points. For instance, he opens by citing Proverbs 26:5 – “Answer a fool according to his folly” – as a justification for engaging with the Greeks’ charges (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). This sets a confident, slightly combative tone from the outset. His Latin is grammatically well-structured, often employing periodic sentences and parallelisms that reflect training in classical texts. At the same time, the vocabulary and imagery draw heavily on Scripture and ecclesiastical tradition (e.g. calling the Church the seamless “tunic of Christ” that heresies try to tear (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource)).

One noticeable stylistic strategy is Ratramnus’s use of rhetorical questions and exclamations to challenge the Greeks’ assertions. For example, responding to the false claim about an Easter lamb on the altar, he asks: “Do they not plainly lie? Have they no fear of the scripture: ‘You will destroy all who speak lies’?” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). Such questions, posed and immediately answered with scriptural rebuke, give the text a lively, oratorical flavor – as if Ratramnus is holding a disputation with an imaginary opponent. He does not shy from strong language when he feels the Greeks have crossed into error. In one breath he describes their accusations as “monstrous” and born of folly or pride (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). In another, he pointedly says the Greeks “condemn themselves by heretical depravity” for denying the Filioque (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). These barbs are often reinforced by authoritative quotes – he follows the “heretical depravity” charge by warning that blasphemy against the Holy Spirit is unforgivable, citing Christ’s words in Mark 3:29 (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). This technique of interweaving his own argument with biblical citations is a hallmark of Ratramnus’s style, lending weight to his words by rooting them in a higher authority.

Use of Sources: Ratramnus displays impressive erudition, extensively citing Church Fathers, councils, and Scripture (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com). He appeals to Augustine, Jerome, Gregory the Great, and other Latin Fathers to bolster the Filioque doctrine, often pointing out that even venerable Greek saints (like Athanasius or Basil, via their Latin translations) spoke of the Spirit in ways consonant with the Filioque. He also invokes early councils (Nicea, as discussed, and possibly others like Sardica or local synods) to justify Latin practices. Notably, he even brings in non-ecclesial writers like Josephus – at one point citing Josephus’s historical testimony to argue that diversity of religious customs can exist without disunity of religion (Knowledge of the Past (Part I) - Writing the Early Medieval West) (Knowledge of the Past (Part I) - Writing the Early Medieval West). This breadth of reference showcases the Carolingian scholarly method: Ratramnus writes as a master of florilegia, stringing together authorities to make his case. Yet, unlike a dry compendium, the work is well-organized and each citation is woven into a coherent argumentative flow.

Structure and Reasoning: The treatise is carefully structured into four books, which helps Ratramnus deploy a logical progression: first tackling false accusations and doctrinal fundamentals (Book I and II focus largely on preliminary matters and then the Holy Spirit), then deeper theological proofs (Book III continues the Trinitarian discussion), and finally ecclesiastical and practical issues (Book IV deals with church authority and customs) (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com) (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia). He even mentions that he will not follow the exact order of the Greek objections, because that order was poorly arranged “by the levity of their minds”, and instead will address them in a more sensible sequence (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). This editorial comment reveals his methodical mindset: he aims to reframe the debate on his own terms. Each book is subdivided into chapters addressing specific topics (e.g. “That the Holy Spirit proceeds from Father and Son – the Greeks likened to Arius” as one chapter heading (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource)). These headings (likely added by later editors or present in the manuscript tradition) show Ratramnus’s argumentative clarity – he explicitly compares the Greeks’ denial of Filioque to the Arian heresy, a calculated rhetorical comparison to discredit their position by association (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource).

In terms of tone, Ratramnus strikes a balance between conciliatory and confrontational. When talking about differences in custom, his language becomes irenic: he speaks of “our ancestors held these things and we hold them; nothing new is being introduced”, and emphasizes common faith (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). He even allows that diversity of rites is acceptable and not every church has the same practices (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource), a generous acknowledgment aimed at calming Greek anxieties about uniformity. However, when doctrinal truth is at stake (like the procession of the Spirit or authority of the Roman Church), Ratramnus writes with passion and sharpness, not hesitating to call the Greek stance “blasphemy” or “pernicious”. This rhetorical modulation is a deliberate strategy: he is conciliatory where possible, but uncompromising where necessary. It gives the text a dynamic quality – at times reading like an olive branch, at times like a scathing polemic.

Linguistically, Ratramnus’s Latin is generally straightforward, avoiding overly convoluted or newly coined words. He does, however, employ some technical theological and legal terms of the era. For example, he refers to the Greeks’ “haereseos pravitas” (the depravity of heresy) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource), a strong phrase from canon law rhetoric, and speaks of clerics not having “mulieres subintroductae” (secret women living with them) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage) when discussing Nicene discipline – a technical term in Latin ecclesiastical parlance for concubines or unofficial wives. His familiarity with such terminology shows that he writes as a theologian-canonist. Yet he always explains or contextualizes these terms so that his point is clear to his audience. The overall register of the text is educated and formal, but not so lofty as to be obscure – it was likely intended for fellow clergy and educated monks/bishops in the Frankish realm, and perhaps to be sent to Rome or even (if translated) to the Greeks.

In summary, Ratramnus’s style in Contra Graecorum Opposita can be characterized by: clarity of argumentation, rich authoritative support, and a mix of polemical zeal and irenic counsel. It is a work that reads as both an intellectual theological treatise and a vigorous apologetic tract. Little wonder that contemporaries praised it highly – it was deemed “his best dogmatic work”, combining solid content with eloquent form (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com) (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia).

Influence and Reception

Immediate Impact (Latin West): In Ratramnus’s own day, Contra Graecorum Opposita earned him considerable renown. It is recorded that he “won most glory in his own day” through this work (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library). The treatise was valued as a timely and effective defense of the Latin position during the East–West controversy sparked by Photius’s encyclical in 867 (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library). Pope Nicholas I died in 867 before seeing East–West unity restored, but the issues Ratramnus addressed did not disappear. In 869, a council in Constantinople (considered by the West as the 8th Ecumenical Council) condemned Photius and reaffirmed the Roman positions – one can surmise that the kind of arguments Ratramnus articulated bolstered the Frankish and papal delegates’ confidence in pressing the Filioque and papal authority. His emphasis on unity of faith and legitimacy of diverse customs may have helped Latin leaders approach the Greeks with a mixture of firmness and conciliation. For example, when Pope John VIII in 879 later reconciled with Photius (briefly lifting the schism), it was on the basis that the Greeks would maintain their creed without Filioque while not condemning the Latin usage – essentially reflecting Ratramnus’s principle that difference in custom (even liturgical formula) need not equate to difference in faith. Ratramnus’s work provided a theological toolkit for such negotiations, clarifying which points were non-negotiable (Trinitarian dogma, papal primacy) and which could be left to legitimate variety.

Within Western scholarly circles, the treatise likely circulated in manuscript and informed other Carolingian thinkers. We know Ratramnus sent a copy to the bishops who commissioned it (the province of Reims) (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia), and it probably reached Rome. The Frankish Church of the 9th century, which had earlier debated the Filioque at the 809 Council of Aachen, now had in Ratramnus’s opus a comprehensive apology for the doctrine. His quotations from Church Fathers and his reasoned approach were a resource for later theologians. Indeed, in subsequent centuries, Latin theologians engaging with the Greeks echoed many of Ratramnus’s arguments (whether or not they directly knew his text). For instance, in 1054 during the Great Schism, Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida wrote a treatise against the Greeks’ criticisms; his points – defending Filioque, Roman primacy, and Latin rites like unleavened bread – parallel Ratramnus closely. While Humbert does not cite Ratramnus by name, the intellectual lineage is evident. Similarly, in the 13th century, St. Thomas Aquinas and others wrote Contra Errores Graecorum or De Processione Spiritus Sancti, again using patristic testimonies to convince Greek theologians of the Filioque – a method that Ratramnus had pioneered in detail (Philip Schaff: History of the Christian Church, Volume IV: Mediaeval …). The idea that “the great richness of diversity is not opposed to the Church’s unity”, a sentiment found in Ratramnus’s work, would resurface centuries later in ecumenical principles (Stop Ragging on the Protestants - Orthodox Christian Theology). In short, Ratramnus’s treatise became part of the West’s arsenal of apologetics in addressing the Greek Church, even if it was not always explicitly credited.

Influence on Later Thought: One area where Ratramnus had a notable (if underappreciated) influence is the concept of unity in essentials, diversity in non-essentials within the Church. His assertion that varying customs did not break communion in the early Church (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) prefigures the famous maxim “unity in necessary things, liberty in doubtful things, charity in all things.” Medieval Latin churchmen like Anselm of Havelberg (12th c.) echoed this idea when dialoguing with the Greeks, proposing that East and West could reunite despite different rites – a direct spiritual descendant of Ratramnus’s plea for respecting legitimate diversity (Knowledge of the Past (Part I) - Writing the Early Medieval West) (Knowledge of the Past (Part I) - Writing the Early Medieval West). In the long view, Ratramnus’s work stands as one of the earliest comprehensive attempts at what we might call Latin apologetics vis-à-vis Eastern Orthodoxy. It set a precedent and provided source material for later discussions on the Filioque and papal primacy, topics that would resurface at councils such as Lyons (1274) and Florence (1439). At the Council of Florence, for example, Latin theologians used many patristic quotations to persuade the Greek delegation that the Filioque was compatible with Greek patristic tradition. Though not directly citing Ratramnus, they were following the modus operandi that Ratramnus had exemplified – compiling evidence from Greek fathers like St. Basil and St. Cyril to bridge understanding. One could argue that Contra Graecorum Opposita was a forerunner to those union council arguments, emphasizing continuity of doctrine across East and West.

Reception among Greek Christians: On the Byzantine side, reception of Ratramnus’s work was, unsurprisingly, negative or negligible. The treatise was written in Latin for a Latin audience, and there is no evidence it was translated into Greek at the time. Thus, Greek churchmen of the 9th century likely learned of its content only indirectly (if at all). Photius himself remained unconvinced by Latin arguments – in fact, he doubled down by composing his own treatise, Mystagogy of the Holy Spirit, which offered a systematic refutation of the Filioque from the Eastern theological perspective (Mystagogy of the Holy Spirit - Wikipedia). This Greek counter-treatise (written a bit later, in the 880s) can be seen as the mirror image of Ratramnus’s work: where Ratramnus gathered Latin and Greek fathers in support of Filioque, Photius gathered Eastern patristic quotes against it. The theological impasse persisted, and sadly, the temporary reconciliations achieved in 869 and 879 unraveled. By 1054, the estrangement became permanent, with mutual excommunications. By that time, any influence Ratramnus’s conciliatory message had was overshadowed by new polemics and centuries of mistrust.

In later medieval Byzantium, Ratramnus’s name was virtually unknown – he did not figure in Greek polemical literature (which instead targeted more prominent Western authorities like Augustine or later scholastics). The Eastern Church’s stance remained that the Filioque was a Western aberration; thus, from their perspective, Ratramnus’s defense was not accepted but seen as an example of Frankish theological deviation. However, it’s worth noting that the concept of allowing different customs that do not harm faith (which Ratramnus advocated) did find echoes in some more conciliatory Eastern thinkers in union dialogues. For example, at the Council of Florence, Greek bishop Bessarion, who favored union, effectively embraced the principle that differences in liturgy (like leavened vs unleavened bread) could be tolerated within one Church. Such openness aligns with Ratramnus’s vision, even if there’s no direct line of transmission.

Legacy: In the Latin West, Contra Graecorum Opposita eventually fell into obscurity along with Ratramnus’s other writings. During the High Middle Ages, the work was not widely copied or studied, as other issues took center stage and other authors (like Anselm of Canterbury’s De Processione Spiritus Sancti) became more immediately relevant in the ongoing East–West debates. Ratramnus’s more controversial Eucharistic treatise ironically gained more posthumous notoriety (being condemned and later rediscovered in the Reformation) (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com) (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com), whereas his anti-Greek treatise did not undergo such a dramatic rediscovery. It survived in manuscript and was finally printed in the 17th century (by scholar Jean Mabillon, or earlier by Jacques Sirmond) and included in Migne’s Patrologia Latina vol. 121 in the 19th century. Modern scholars have found it a fascinating window into Carolingian theology and early East–West relations. Historians of doctrine note its role as one of the first Latin corpora of arguments on the Filioque (Ratramnus - Britannica). Its call for unity of faith and diversity of practice can even be seen as a precursor to today’s ecumenical outlook that different rites (Latin, Byzantine, etc.) can coexist in one Church. In Eastern Christian memory, however, Ratramnus’s work left little direct trace – it was a polemical treatise firmly from the Latin viewpoint, and the Greek Orthodox Church continued to regard the underlying positions (Filioque, papal supremacy) as breaches of apostolic faith, irrespective of Ratramnus’s patristic citations.

In sum, Contra Graecorum Opposita had a significant immediate impact in strengthening the Latin defense against Byzantine criticisms and set the tone for future theological defenses. Its long-term influence was felt more in the West’s approach to East–West dialogue (providing arguments and a framework of thinking) rather than in any change of heart on the Eastern side. Today, it stands as an important scholarly work illustrating the 9th-century Latin intellect engaging with the Greek East – a cornerstone in the sad but intellectually rich history of the widening schism.

Comparison with the Original Latin Text and Its Translation

Nuances of Language: Comparing the original Latin of Contra Graecorum Opposita with any translation (where available) reveals several important nuances. Ratramnus’s Latin is rich in technical and rhetorical flavor that a translation must carefully convey. For instance, the very title in Latin, “Contra Graecorum opposita Romanam ecclesiam infamantium”, literally means “Against the things set forth by the Greeks who are defaming the Roman Church.” Some translations shorten this to “Against the objections (or slanders) of the Greeks” (Tag: Gregory the Great - Roger Pearse). The word opposita carries the sense of proposed objections or opposing arguments, but also hints at a confrontational posture. A translator choosing “objections” might capture the formal sense, whereas “slanders” emphasizes the hostile intent (as Ratramnus surely meant – he saw the charges as calumnies). Thus, even the title involves a nuanced choice: balancing literal accuracy with the connotation of polemic.

Ratramnus frequently uses strong Latin adjectives and legalistic terms that pack more weight in the original than a simple English rendering might show. For example, he labels the Greek emperors’ interference as “monstruosi… praeceptores” – literally “monstrous instructors” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) – a phrase that conveys both absurdity and horror. An English translation might call them “strange teachers” or “preposterous teachers,” which softens the imagery. Likewise, when he says the Greeks “se haereseos pravitate condemnant”, a literal translation is “they condemn themselves by the depravity of heresy” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). In English one might simplify this to “condemn themselves as heretics,” losing the nuance of pravitas (perversity or moral crookedness) that Ratramnus attached to heresy. The Latin phrase evokes the longstanding ecclesiastical rhetoric about the “haeretica pravitas” that council canons often aimed to extirpate – a flavor that an English reader might not catch unless the translator is deliberate about it. Ratramnus’s calling the Greek position a “blasphemy against the Holy Spirit” also rings with grave severity in Latin (he notes it’s “irremissibile peccatum”, an unforgivable sin (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource)). A translation will likely communicate the content of that accusation, but the reader should sense the gravity and shock value it would have carried in 868.

Another subtle aspect is Ratramnus’s use of inclusive Latin qualifiers when trying to be diplomatic. For instance, he refers to the Greeks (when chiding them on custom differences) conditionally as “si tamen Ecclesiae filii sunt, et unitatis catholicae sectatores” – “if indeed they are sons of the Church and followers of catholic unity” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). A translator might render this clause straightforwardly, but the nuance is that Ratramnus is questioning, ever so politely, whether his opponents are truly remaining within the Catholic fold. The Latin phrasing is somewhat mild (couched as a conditional), yet insinuating. In English, this might become a more blunt statement unless carefully handled (e.g. “if, that is, they count themselves children of the Church…”). Such conditional barbs are a common Latin rhetorical device that can flatten out in translation.

Faith vs Custom Terminology: One of the most critical nuances in the work is Ratramnus’s distinction between fides (faith) and consuetudo or instituta (customs/practices). In Latin he writes, “Aliud est de habitu… discernere, et aliud de unitate fidei similiter sentire” – “It is one thing to differ in habit/usage, and another to think alike regarding the unity of faith.” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). He further says the Churches did not lose communion “propter alternae consuetudinis commutationem” – “because of a change in each other’s custom” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). A good translation must preserve this contrast clearly. Phrases like “unitatem fidei” (unity of faith) vs “diversae consuetudinis” (diverse custom) encapsulate his thesis. Translations have rendered these ideas as “unity in faith, diversity in practice” or similar. For example, one modern paraphrase inspired by Ratramnus states, “the great richness of such diversity is not opposed to the Church’s unity.” (Stop Ragging on the Protestants - Orthodox Christian Theology) This captures the spirit, though not the letter, of Ratramnus’s Latin. The nuance in Latin is that unitas implies a tight bond or oneness, whereas diversitas of custom is acknowledged without using a pejorative term. He deliberately uses consuetudo (custom) rather than something like error or superstitio when speaking of Greek practices he disagrees with, to show he considers them customary differences, not heresy (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). A translator must be attentive to this choice of words; translating consuetudo simply as “tradition” or “custom” is accurate, but the reader should appreciate that Ratramnus is classifying those issues as non-doctrinal. In the original Latin, that distinction is clear in the diction; a good commentary or footnote in a translation might highlight it to ensure the nuance isn’t lost on a modern reader.

Scriptural and Patristic Quotes: Ratramnus peppers the Latin text with quotations that a translator faces decisions on how to render. He often uses the Latin Vulgate text for Scripture. For instance, he quotes John 15:26 as “Paracletus, quem ego mittam vobis a Patre, Spiritum veritatis, qui a Patre procedit” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource). An English translation might substitute the known RSV or NIV wording of that verse (“the Advocate, whom I will send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father…”). Doing so ensures the reader recognizes the scripture, but it might obscure the slight emphasis Ratramnus is making by placing “quem ego mittam” in italics (as he does) to stress the Son’s role. Similarly, when he cites the Nicene Creed or patristic phrases, the translator must decide whether to use established English versions of those texts or translate Ratramnus’s Latin verbatim. The Creed’s phrase “Spiritum sanctum… ex Patre procedentem” (which the Greeks profess without “Filioque”) appears in his argument. A translation might note the absence or presence of “and the Son” explicitly to draw out the controversy – something the Latin reader would infer from context. Overall, while the content of Ratramnus’s citations is usually clear, the contextual emphasis he places (by positioning or by commentary around the quote) is the real nuance. A translator needs to sometimes add a brief explanation to convey why Ratramnus is quoting a given Father. For instance, he quotes St. Augustine calling the Holy Spirit “Spiritus amborum” (the Spirit of both [Father and Son]) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) – a translator might footnote that this is from Augustine’s De Trinitate, to indicate the pedigree of the quote. The original Latin audience, steeped in patristics, might recognize it, but a modern audience might not catch the significance without annotation.

Tone and Formality: Ratramnus’s polite yet firm tone can be tricky to maintain in English. Latin has a way of being very direct and formal at the same time. For example, “Quis ferre possit…?” – “Who could endure that…?” (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) – is a polite rhetorical way to say “This is intolerable.” An English translation might just say “It is unbearable that…” without the question, thus sounding more blunt. Throughout Contra Graecorum Opposita, Ratramnus uses such turns of phrase that soften an accusation by phrasing it interrogatively or hypothetically. Preserving these in translation can keep the flavor of Ratramnus’s discourse. Similarly, he occasionally uses first-person plural (“we”) when speaking for the Latin Church, and direct second-person (addressing the Greeks as “you” implicitly). A translator into English might make those shifts more explicit (“you Greeks claim… we Latins maintain…”), whereas the Latin may leave the subject implicit. Attention to these pronouns and perspectives ensures the dialogical character of the text comes through – it is, after all, framed as a reply to an attack.

Availability of Translations: It is worth noting that Contra Graecorum Opposita has not been widely available in English. Portions have been translated in academic contexts (for instance, a scholarly English translation of Book IV chapter 6 was published online, dealing with clerical marriage) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage), and an old Library of Christian Classics volume (1957) reportedly includes some of Ratramnus’s work (Ratramnus - Britannica). A complete English edition, however, is difficult to find – interested readers often have to work from the Latin or a modern language version. (A French translation, “Contre les diffamations des Grecs”, exists and has been cited by scholars (Ratramnus - “Contra Graecorum Opposita”, available anywhere in English? : r/Catholicism).) This scarcity means that nuance can sometimes be lost in secondary summaries. When comparing the Latin to any given translation, one should be aware of the translator’s choices. For example, one French translator might render Ratramnus’s invective more mildly, or an English summary might omit the more scathing remarks to focus on theological content. Thus, examining the original Latin reveals Ratramnus’s full rhetorical force. Phrases like “Perdes omnes qui loquuntur mendacium” (the Psalm verse “Thou shalt destroy all who speak lies”) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) stand out starkly in Latin, placed there to sting the conscience of his opponents. A translation will convey the meaning, but only the Latin shows the exact placement and sound of the Psalm in his argument.

In conclusion, a careful comparison highlights that Ratramnus’s argumentation is as much in how he says things as in what he says. The original Latin text carries a blend of logical clarity and passionate conviction, conveyed through specific word choices, quotes, and rhetorical devices. A good translation will strive to maintain this blend – preserving technical terms like Filioque, subintroducta, chrismate untranslated where necessary, and faithfully reflecting his scriptural allusions – so that the modern reader can appreciate the scholarly yet ardent voice of Ratramnus. Critical nuances, such as the distinction between faith and custom, the severity of calling something heresy, or the polite barbs aimed at imperial meddlers, must be conveyed for a true sense of the work. While translations make the content accessible, reading the Contra Graecorum Opposita in the original Latin offers the most authentic insight into Ratramnus’s mindset and the flavor of 9th-century theological debate. Each Latin phrase is a window into the Carolingian intellectual world – a world of deep respect for tradition, earnest desire for Christian unity, and vigorous defense of one’s church in the face of challenges.

Sources: Ratramnus’s Contra Graecorum Opposita in Patrologia Latina vol. 121 (columns 223–346) (Patrologia Latina/121 - Wikisource) (Patrologia Latina/121 - Wikisource); New Catholic Encyclopedia via Encyclopedia.com (Ratramnus of Corbie - Encyclopedia.com); Catholic Answers Encyclopedia (Ratramnus - Catholic Answers Encyclopedia); Britannica Online (Ratramnus - Britannica); 1911 Encycl. Britannica (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Ratramnus - Wikisource, the free online library); Excerpts from Ratramnus’s text (Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource) (Contra Graecorum opposita (Ratramnus Corbeiensis) - Wikisource); Charles West, trans. of Contra Graecorum… IV.6 (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage) (Turbulent Priests - Carolingian views of marriage).

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube