Liber de grandine et tonitruis (c.820)

Listen to Audio Analysis

Listen to a brief analysis of this text

An influential Carolingian treatise by Archbishop Agobard of Lyon (c. 820) refuting the widespread folk belief in weather-making sorcerers (tempestarii). The text presents theological arguments that only God controls weather phenomena, recounts the author's intervention to save alleged "sky sailors" from lynching, and represents an early rational approach to natural phenomena that influenced medieval canon law before being overshadowed by later witch-hunt theology.

Historical Context and Authorship

Liber de grandine et tonitruis is a Carolingian-era treatise traditionally attributed to Agobard of Lyon (Agobardus Lugdunensis), who served as Archbishop of Lyon in the early 9th century (r. 816–840) (Liber de grandine et tonitruis - Wikisource). It was likely composed in the 820s AD, during Agobard’s efforts to reform popular religious beliefs in his diocese. The text addresses a widespread folk belief in Gaul and the Frankish Empire that witches or sorcerers (dubbed tempestarii, “storm-makers”) could magically control the weather – specifically, that humans could cause hailstorms and thunder at will. Agobard opens by lamenting that “nearly all people, noble and ignoble, urban and rural, old and young” in his region held this superstition. The treatise’s origin is closely tied to this context: the Carolingian church was combatting vestiges of paganism and magical thinking among newly Christianized populations. Indeed, Charlemagne’s laws (e.g. the Council of Paderborn, 785) had outlawed belief in witchcraft and weather-magic, even prescribing the death penalty for those who killed alleged witches “blinded by the Devil, in the pagan manner” (Council of Paderborn - Wikipedia). Agobard’s work can be seen as a local, episcopal enforcement of this broader Carolingian policy to uproot pagan superstitions.

As for authorship, there is little doubt that Agobard wrote De grandine et tonitruis. It appears among his collected works in Patrologia Latina vol. 104. Agobard was an influential churchman and theologian of his time, known for other polemical writings against heresies, Jewish rituals, and image worship. His clear, authoritative voice and personal witness in the text (he recounts events that he saw “in nostra praesentia,” “in our presence”) strongly support his authorship. Historically, the treatise provides a rare window into the popular beliefs of early medieval Francia – so much so that modern historians consider it “one of the most famous [texts] of the Carolingian world” for what it reveals about 9th-century folklore and church response.

Theological and Philosophical Themes

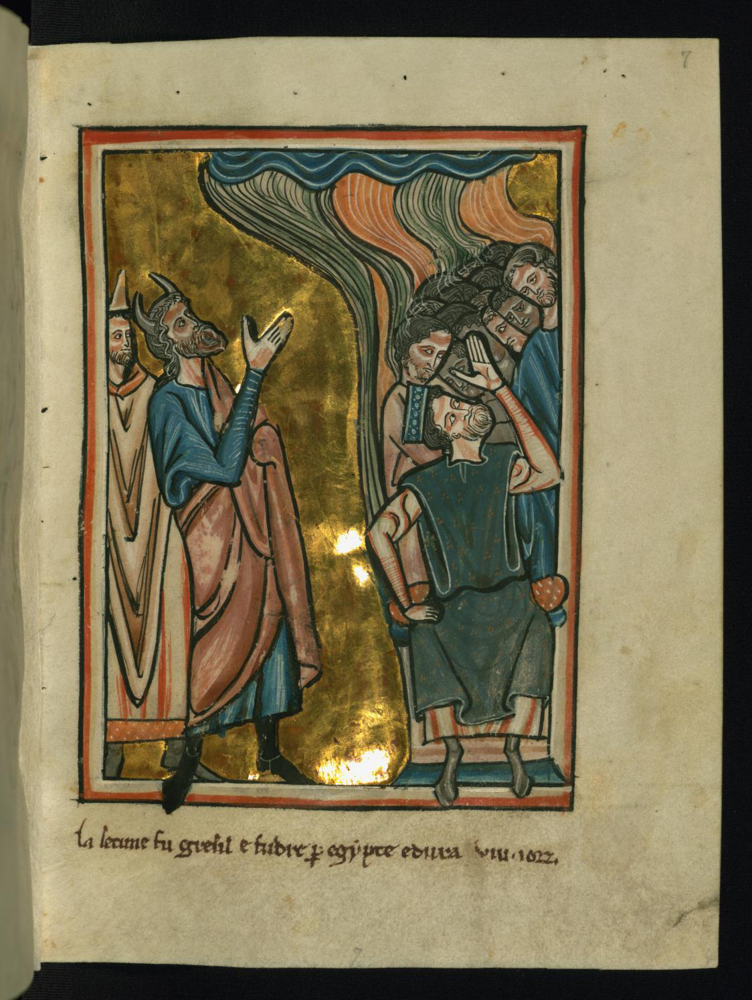

Medieval theologians viewed weather as an instrument of divine will. This 13th-century Bible illustration shows God sending hail and fire upon Egypt (Seventh Plague, Exodus 9), underscoring that storms were ultimately attributed to God’s power in Christian thought.

At its core, Liber de grandine et tonitruis is a theological refutation of magical explanations for natural phenomena. Agobard insists that hail, thunder, and lightning are governed solely by God’s providence, never by human sorcery or demonic tampering. He frames the belief in weather-making magicians as not only false but blasphemous. In the opening section, he argues that if one claims a human can do what only God can do (raise storms) and conversely that God is not the one doing it, that person commits a grave lie against the Creator. Agobard calls it an error “falsum… absque ambiguo” (undoubtedly false) and “a most deadly lie” to attribute “opus divinum homini” – the work of God to a mortal. This is a strong theological stance on divine causality: all natural phenomena, even destructive ones, fall under divine control. He supports this by citing Scripture extensively. For example, he quotes the Book of Exodus on the plague of hail – “Dominus dedit tonitrua et grandinem… pluitque Dominus grandinem super terram Aegypti” (“The Lord sent thunder and hail… and the Lord rained hail upon the land of Egypt”) – emphasizing “ecce… solum Dominum ostendit creatorem et auctorem grandinis, non aliquem hominem” (“behold, this passage shows that the Lord alone is the creator and author of hail, not any man”). Such examples reinforce the message that weather is a tool of divine agency, often used in the Bible to punish the wicked or test the faithful.

A related theme is divine justice and the moral meaning of natural events. Agobard does not explicitly develop a theory of storms as punishment for sin, but by invoking biblical incidents he implies a moral dimension to weather. He recounts how the prophet Samuel called upon God to send thunder and rain as a sign to rebuke the Israelites for wrongdoing, causing the people to repent (citing 1 Samuel 12:16–18). Agobard pointedly contrasts the Israelites’ penitent reaction to divine thunder with the response of “nostri semifideles” (“our half-believers”) in Gaul, who foolishly blame tempestarii instead of recognizing God’s hand and correcting their lives. The subtext is that thunder should inspire pious fear and repentance, not superstitious scapegoating. Throughout the treatise, Agobard weaves in moral exhortation: those who propagate the false belief in human-made storms are liars imperiling their souls, akin to the liars and sorcerers condemned in Scripture. He quotes warnings such as “os quod mentitur occidit animam” (“the lying mouth kills the soul”) and reminds readers that in the Apocalypse, sorcerers (venefici) and all who “love and practice falsehood” are excluded from the heavenly city. Thus, the theological theme of truth vs. falsehood is central – embracing the truth of God’s omnipotence and rejecting the false attribution of divine power to magicians is portrayed as a matter of salvation.

To drive home these points, Agobard exposes the specific folk mythology underpinning the error. In a striking passage, he describes the legend of Magonia: a fanciful aerial land “from which ships come in the clouds” to steal grain knocked down by hail. According to local belief, these cloud-ships are manned by “nautae aerei” (sky sailors) who collaborate with the tempestarii. The storm-makers on earth magically produce storms to ruin crops, and the sky sailors then pay them for the harvested grain which they ferry away to Magonia. Agobard recounts that the delusion was so strong that on one occasion, a mob in his region claimed to have captured four people who “fell from these ships”. The captives – “three men and one woman” – were held in chains and exhibited in a public assembly so that they might be stoned to death as presumed Magonian sailors. Agobard intervened in person at this gathering. After much argument, “vincente veritate” (“with truth victorious”), he persuaded the crowd to release the innocents, and those who had produced them were put to shame, “confusi sunt, sicut confunditur fur quando deprehenditur” (“they were confounded as a thief is when caught”). This dramatic anecdote illustrates the depth of superstition among the people and sets the stage for Agobard’s scriptural rebuttal. It also shows Agobard’s pastoral concern – he was compelled to correct not just an abstract doctrine but a dangerously concrete practice (attempted lynching of supposed witches).

The philosophical worldview behind Agobard’s arguments is a Christianized natural philosophy where nature operates under God’s law and angels, not under independent occult forces. He acknowledges that his contemporaries offer various supernatural explanations for storms – some attribute them to demons or “evil angels,” others to the magic of enchanters – but he deliberately rejects these in favor of a pure doctrine of first causes (God’s will). Agobard thus aligns with an Augustinian perspective that Satan and his minions have no autonomous power over nature. If anything, only God or His legitimate servants (the saints or angels as agents of God) can cause extraordinary weather. As one commentator summarizes Agobard’s main point: “only God, [or] saints and angels can change weather, not heathen magic” (france - Are there any sources on the Tempestarii? - History Stack Exchange). In other words, weather miracles are real but belong to the realm of Providence and holy intervention, not to pagan sorcery. This implicitly situates phenomena like hail and thunder within the medieval Christian understanding of a rational, divinely-ordered cosmos. Agobard wants his flock to view storms not as chaotic curses conjured by witches, but as events guided by God’s providence – whether for testing, punishment, or the natural functioning of Creation.

Literary and Linguistic Features

Literarily, De grandine et tonitruis is a concise polemical treatise with a didactic tone. Agobard structures the text in a clear, reasoned manner, almost like a sermon or disputation. The surviving manuscript tradition (and the Patrologia Latina edition) divides it into short chapters or sections (numbered I, II, III, etc.), signaling a logical progression. In Section I, Agobard introduces the problem – the widespread belief in manufactured hailstorms – and states the necessity of examining this belief “ex auctoritate divinarum Scripturarum” (“on the authority of divine Scriptures”). Section II provides the illustrative anecdote about Magonia and the attempted stoning, which serves to vividly demonstrate the error’s prevalence and dangers. Section III and following then marshal a battery of biblical quotations and theological arguments to refute the superstition point by point. This methodical layout reflects Agobard’s pedagogical intent: he is teaching his readers (or listeners) by first identifying the erroneous belief, then disproving it through scripture and reason, and finally exhorting them to correct their mindset.

The style of the Latin is pointed and authoritative, yet accessible. Agobard writes in the relatively plain Latin of the Carolingian Renaissance, influenced by biblical language. He freely quotes the Latin Vulgate Bible – sometimes weaving in verses verbatim – which gives his prose a scriptural cadence. For example, when condemning the lie of weather-magic, he inserts verses such as “Perdes omnes qui loquuntur mendacium” (“Thou shalt destroy all who speak lies”) and “Testis falsus non erit impunitus” (“A false witness will not go unpunished”). These serve both as evidence from authority and as rhetorical amplification. Agobard often lets the Bible speak for him, concluding that it will be “ipsa veritas” (truth itself) that “expugnet stultissimum errorem” (“will drive out this most foolish error”). This heavy reliance on biblical intertextuality is typical of Carolingian ecclesiastical writing, where Scripture was the ultimate intellectual arsenal.

Despite the predominance of scripture, Agobard’s own voice comes through in forceful, at times scathing language. He does not hesitate to call out the folly of his opponents. He describes those taken in by the tempestarii superstition as “tanta dementia obrutos, tanta stultitia alienatos” – “overwhelmed by such madness, so estranged by stupidity” – that they believe in the cloud-ships of Magonia. Such phrasing (invoking dementia and stultitia) shows a flair for invective common in patristic polemics. Agobard’s tone is indeed “a rant on charlatans” in parts (france - Are there any sources on the Tempestarii? - History Stack Exchange), reflecting his frustration with the persistence of pagan nonsense among baptized Christians. Yet alongside the harsh epithets, he maintains a rational and conciliatory approach. The Magonia incident ends with truth triumphing and even the would-be executioners penitent (“confusi”, ashamed). Agobard thus models the ideal outcome: not just debunking the false belief, but bringing the misguided back to the truth of the Church.

In terms of genre, the work straddles a few categories. It is often referred to as a liber (book) or tractate, but it also has qualities of a pastoral letter or homily addressed to Agobard’s flock. There is no direct addressee or epistolary greeting, so it is not a letter in form; rather, it reads like a public admonition or open sermon intended to circulate. Agobard likely wrote it for educated clergy and lay readers in his archdiocese, who could then convey its teachings to the general populace. The Latin is straightforward enough that portions could be paraphrased in the vernacular from the pulpit. He even incorporates local terminology: for instance, he mentions that as soon as rustics see lightning and hear thunder, they declare “Aura levatitia est”. The term aura levatitia appears to be a popular incantation or concept (perhaps meaning “a raised wind” in rustic Latin). By acknowledging and explaining such terms, Agobard shows an awareness of the folk vocabulary of magic. He then immediately subsumes it under his theological framework, asserting that common folk attribute it to incantations by men called tempestarii. This mix of erudite scripture and down-to-earth language about charms gives the text a unique linguistic character: it oscillates between the lofty and the colloquial. In summary, Agobard’s writing is lucid, structured, and rich in authoritative references, yet also sharply worded when dismantling what he sees as dangerous foolishness.

Reception and Influence

Liber de grandine et tonitruis had a significant impact both in its immediate context and in the broader development of medieval Christian thought on magic and nature. In Agobard’s own lifetime and region, his stance against weather-magic was reinforced by other Carolingian intellectuals. His contemporary and friend, Archbishop Rabanus Maurus of Mainz, likewise wrote to denounce magical charms and popular superstitions, echoing many of the same biblical arguments (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics). More formally, the Church incorporated this rational view into its decrees. The Canon Episcopi, a famous church ordinance compiled c. 906 (attributed to an earlier Frankish synod), condemned the belief in night-flying witches as a delusion of the devil, very much in the spirit of Agobard’s rejection of Magonia’s cloud-sailors (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics). A synod in Rome (1080) under Pope Gregory VII even wrote to the king of Denmark to forbid prosecutions of weather-making witches, asserting that storms are acts of God alone – a direct theological descendant of Agobard’s position (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics). In short, during the early and high Middle Ages, the mainstream Church regarded weather-magic as pagan superstition with no real power, and On Hail and Thunder was an early and prominent articulation of that view (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics). Medieval penitential books and bishop’s manuals frequently included Agobard-like warnings against attributing misfortune to witchcraft. For example, the penitential of Archbishop Burchard of Worms (circa 1010) asks if anyone believes storms or infirmities are caused by witches, instructing that this belief must be abjured as false. We see in these texts the clear imprint of Agobard’s core idea: that such beliefs are “deceived by the Devil” and must be eradicated from Christian minds (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics).

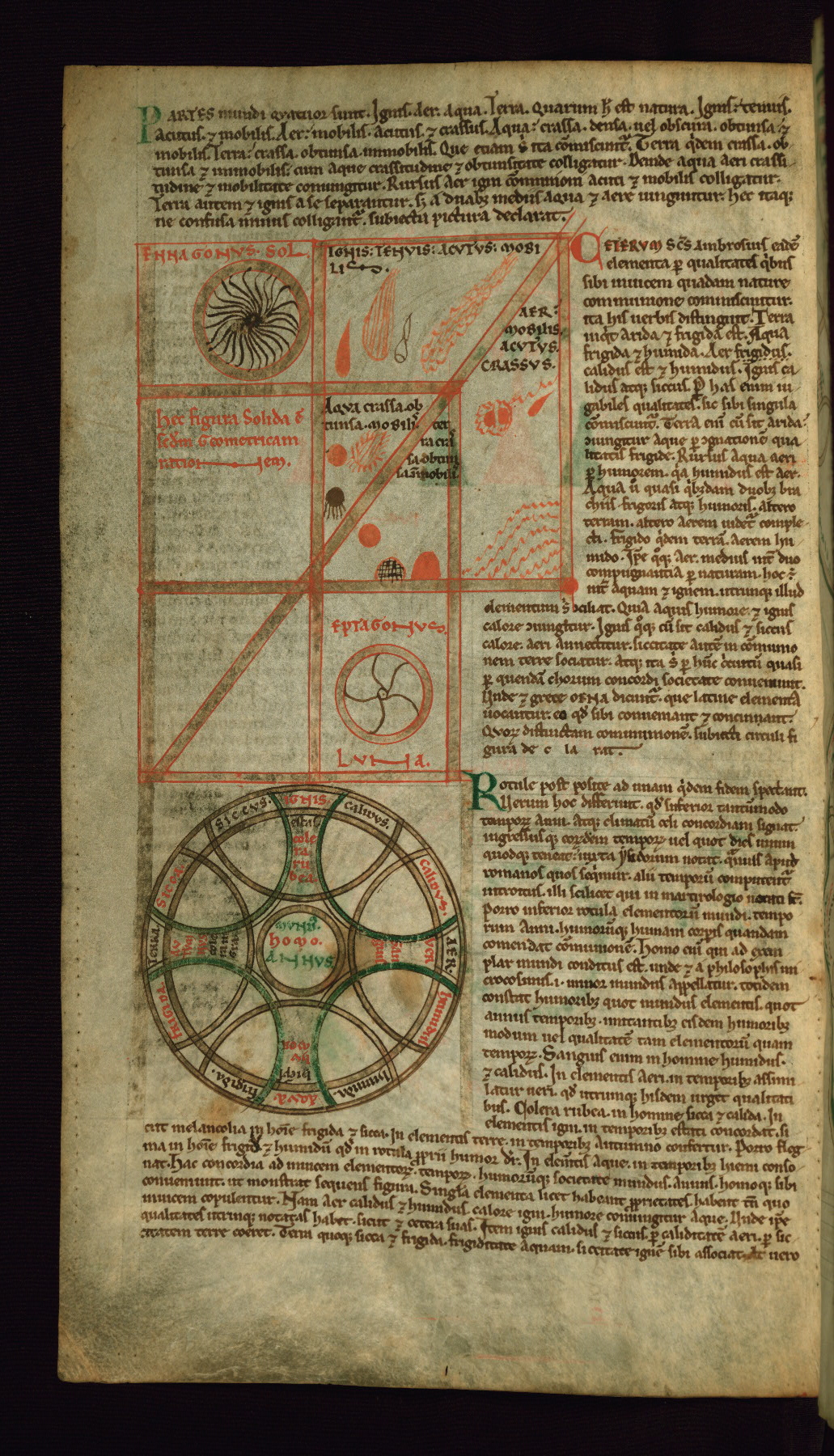

Medieval scholars replaced superstition with learning. This 12th-century cosmological diagram (from Isidore of Seville’s *De natura rerum) visualizes the four elements (earth, air, fire, water) and their qualities, and a wheel of the seasons and humors – symbolizing the harmonious natural order under God. Such diagrams were used in monastic science to explain weather and nature without resorting to magic.*

Despite the Church’s official teaching, popular belief in weather-magic persisted in pockets of Europe. Agobard’s testimony itself, with its account of attempted lynching, shows that clerical admonitions did not immediately erase old beliefs. Medieval chronicles and hagiographies occasionally mention peasants still blaming witches for crop failures or lightning strikes. However, the “received wisdom” among theologians for many centuries was essentially Agobard’s: that witches’ alleged supernatural feats were either fraudulent or demonic illusions, not real physical effects. This consensus began to shift in the later Middle Ages. By the 14th and 15th centuries, a new theology of witchcraft emerged that reintegrated witch-magic as a real, diabolical force (though accomplished only by Satan’s power). Church doctrine evolved to treat making storms through sorcery (maleficium) as a possibility, now classified as a form of heresy in league with the Devil (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics). This doctrinal reversal – essentially a return to believing in the efficacy of witches – paved the way for the tragic witch-hunts of the early modern period (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics) (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics). In that sense, Agobard’s De grandine et tonitruis can be seen as ahead of its time in skepticism: it represents an enlightened position that the later medieval Church would eventually abandon. It is telling that witch-hunters of the XV–XVII centuries did not cite Agobard; his treatise had fallen into obscurity by then, and its content ran counter to the witch-phobic mindset of the inquisitors.

Nevertheless, Liber de grandine et tonitruis enjoyed a measure of influence in the medieval period as a didactic text. It was likely copied in monastic scriptoria (the surviving manuscripts and its inclusion in 19th-century editions attest to its preservation). Its rational, scripture-based approach to natural phenomena complements the encyclopedic and scientific writings of early medieval scholars like Isidore of Seville and Bede. We can imagine that in a monastic school, a teacher might use Agobard’s work alongside cosmological diagrams (like the one above) to drive home the lesson that nature’s patterns are part of God’s design – to be studied and admired, not feared as enchantments. In the context of Carolingian educational reforms, Agobard’s treatise fits the agenda of purifying the faith and promoting a Christian understanding of the world. Its influence is also evident in canon law and pastoral literature that continued to warn against weather-superstitions for centuries after.

In modern times, historians and scholars have rediscovered On Hail and Thunder with great interest. It is frequently cited as evidence of the Carolingian Church’s “war on superstition” and as an early ethnographic account of medieval folk belief. Numerous studies have analyzed it, from anthropological angles (as a glimpse into medieval magical folklore) to the history of science (as an episode in the long debate over natural vs. supernatural causation). The text’s vivid account of Magonia has even given rise in recent decades to comparisons with later myths of airborne beings – it famously inspired the title of UFO researcher Jacques Vallée’s Passport to Magonia (1969), drawing a parallel between medieval and modern sky lore. Thus, the reception of Agobard’s little book has come full circle: once a tool for medieval clergy to educate their flock, it is now studied by scholars to educate us about the medieval mindset. Its legacy lies in illuminating the continuum between faith, science, and superstition in Western thought. In Agobard’s firm conviction that truth and piety must overcome error and fear, we hear a clear echo of the Carolingian Renaissance’s spirit – a desire to align natural philosophy with divine truth, and to guide the faithful away from myth into a more truthful understanding of Creation (france - Are there any sources on the Tempestarii? - History Stack Exchange) (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics).

Sources: Primary text in Patrologia Latina 104; Agobard’s testimony and analysis in English (france - Are there any sources on the Tempestarii? - History Stack Exchange); Carolingian legal context (Council of Paderborn - Wikipedia); modern scholarly commentary on Carolingian magic beliefs; medieval Christian doctrine on witchcraft (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics) (Early Christian resistance to witch hunts - Bible Apologetics).

Side by side view is not available on small screens. Please use Latin Only or English Only views.

Latin Original

English Translation

Text & Translation Information

Enjoy this article? Continue the discussion!

Watch the translation and share your insights on YouTube.

Watch on YouTube